My Last Duchess, by Robert Browning | A portrait of violence

Author

Year

Length

Original language

Genre

By

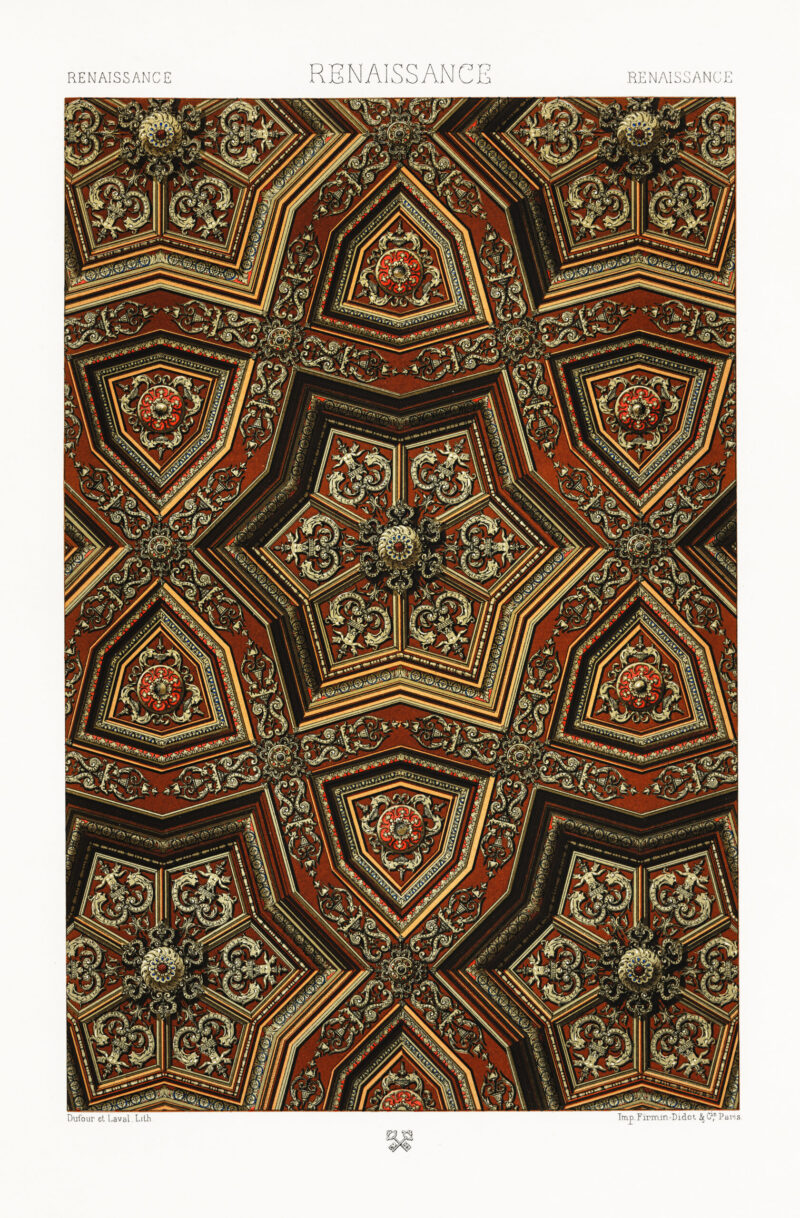

A room full of paintings, sculptures, fine objects. A Duke, and the gloom of curtains, opened to unveil a “wonder” of a portrait. With a few strokes, Robert Browning sets the scene for My Last Duchess, a dramatic monologue originally published in 1842 in the collection Dramatic Lyrics.

Browning was born in South London in 1812 and is one of the best-known Victorian poets alongside poet laureate Alfred Tennyson and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, whom Browning married in 1846. Upon their wedding, the couple moved to Italy and settled in Casa Guidi in Florence, where a museum stands today to celebrate the life and love of the two poets.

Author of several collections of poetry, Browning is especially popular for the historical and fictional characters he depicted using the dramatic monologue. Through this lyric technique, a single character addresses one or more listeners by delving on a specific episode or moment of crisis in his or her life. Thus, the soliloquy offers a unique perspective whose reliability only the reader can judge. In this sense, the speaker in the dramatic monologues reminds of the unreliable narrator of 20th– and 21st-century fiction, exemplified by the protagonists of Abdulrazak Gurnah’s By the Sea.

Still life and the challenged male gaze

In addition to being a dramatic monologue, My Last Duchess is also an ekphrastic poem: in the action of describing a painting, the narrator evokes meanings and ideas that transcend the work of art itself. John Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn is a notable example of ekphrasis, as the poet focuses on two scenes painted on an urn to reflect on beauty, mimesis, and the role of art.

In My Last Duchess, it is Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara from 1559 to 1597, to speak and describe the portrait of his late wife, Lucrezia de’ Medici, whom he married when she was only 13, and who died a few years after the wedding.

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Lines 1-4

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now; Fra Pandolf’s hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Readers get to know Lucrezia through Alfonso’s gaze, who describes her as if he were looking at a still life, an object in his power to control (“none puts by / The curtain I have drawn for you, but I” he claims). However, the vividness of the painting and its lifelike glance exert their own power on the Duke, who soon gets carried away in his monologue. He tells about the “depth and passion” of her gaze, the “spot of joy” in her cheeks, in a crescendo of anger:

Lines 21-24

By looking at the portrait, Alfonso recalls his inability to control and cage her, and accuses her of having disrespected his “nine-hundred-years-old name” with her careless demeanour. The increasing violence of the monologue climaxes in a series of disturbing lines, full of caesuras and punctuation marks. These breaks in the rhythm evoke the sensation of strangling, hinting at the true causes of Lucrezia’s death:

Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Lines 43-46

Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together.

In the final lines of My Last Duchess, Alfonso invites his guest to join the party downstairs, revealing that the meeting is part of his negotiations for a new wife. He thus regains the control that he had lost while looking at the painting, closing the curtains that had shown the challenging gaze of Lucrezia.

Restoring agency: A Marriage Portrait

While Lucrezia’s gaze challenges the Duke even in reproduction, My Last Duchess is all about Alfonso, his jealousy, and his need to regain control. Readers are left to imagine what the 13-year-old Duchess’ life could look like. In 2022, English author Maggie O’Farrel filled this gap by publishing A Marriage Portrait, a historical fiction entirely told from the perspective of Lucrezia de’ Medici.

O’Farrel took inspiration for the novel’s title and plot from both Browning’s poem and Lucrezia’s portrait by Italian painter Alessandro Allori.

In the novel, Lucrezia narrates her own story from early childhood in the lively de’ Medici palace in Florence to the gloom of the Renaissance court in Ferrara, where even Alfonso’s sisters lived in the fear of his wrath. Although drawing from historical sources, O’Farrel greatly fictionalises Lucrezia’s life, and gives access to her most inner thoughts, her creative impulses, and her need to be free from the constraints of marriage and courtly life. Thus, A Marriage Portrait gives agency back to Lucrezia, and allows readers to see the world – and judge Alfonso- through her own eyes.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic