The Catcher in the Rye | Finding one's place in the world

Author

Year

Format

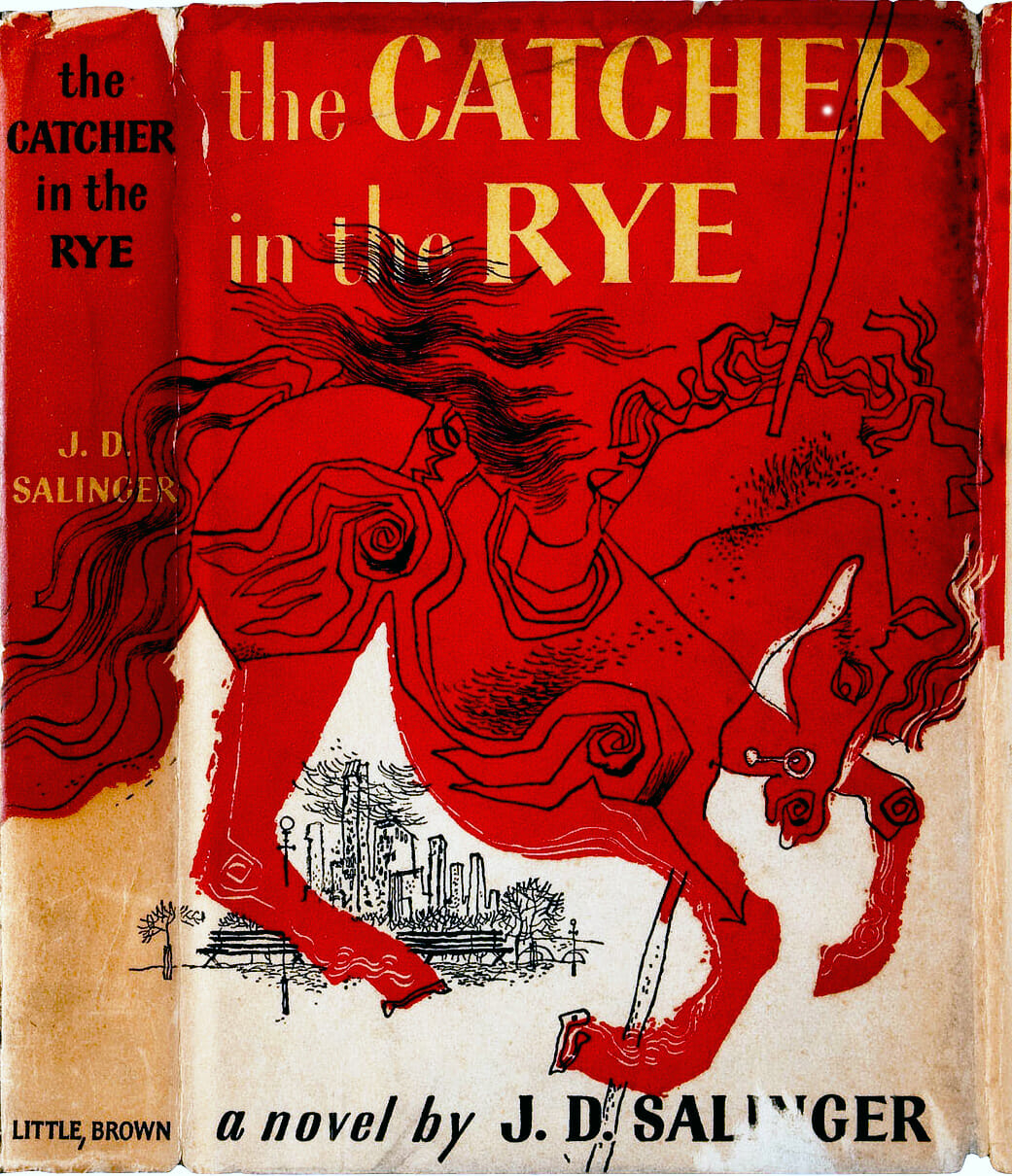

The Catcher in the Rye is the first record on Hypercritic since this book is our talisman, our lucky charm.

To understand the mystery of Holden Caulfield and how this character still manages to embody, seventy years later, a certain kind of weariness, a mixture of fatigue, impatience, melancholy, but above all the anger of adolescence, we must look for references not only in Salinger’s history as a student, very similar to that of his protagonist but also in the circumstances under which Salinger wrote the first chapters of his novel. A novel that compares to other great American classics narrated in the first person such as Huckleberry Finn and The Great Gatsby – whose authors were influential to Salinger, as well as William Shakespeare’s Hamlet in the construction of Holden’s identity.

The novel’s hypnotic spell

The great American critic Harold Bloom believed that Salinger’s voice, though vivid and authentic, does not reach the aesthetic heights of F. Scott Fitzgerald, nor Mark Twain‘s irony, nor Melville‘s epic breadth.

Yet the influence of Salinger and his novel is vast, as the hypnotic spell of his protagonist’s voice, whose jargon is out to date but not its sound, cadence, and musicality, which would influence many authors to come, from Silvia Plath to Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Jay McInerney‘s Bright Lights, Big City, Dave Eggers‘ A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Haruki Murakami‘s Norwegian Wood, Woody Allen’s A Rainy day in New York, the TV show Euphoria, and Billy Wilder or Steven Spielberg, who would’ve liked to adapt it into a movie. But Salinger never authorized any form of visual representation of his work, not even on the cover of the novel.

Holden’s anger

He wrote the first chapters of Holden Caulfield’s New York peregrinations during the Normandy landing. He kept the pages in the lapel of his jacket while trying to survive each new day, and learning from the newspapers that his fiancée, Oona O’Neill, daughter of playwright Eugene O’Neill, had left him for Charlie Chaplin. We don’t know how Salinger felt in those days, but Holden’s anger has become a symbol for entire generations and the human condition of all those who try, yet fail, to find a place in the world.

The story of the novel takes place over just three days during the Christmas holidays. Holden has been expelled from his prep school and returns to the city earlier than expected, only to undergo a series of misadventures that throw him into a state of deepening depression and psychological instability. He is unable to relate normally to other human beings: neither old friends, nor former professors, nor girls he likes, and casual encounters turn out even more disastrous.

The experience of failure

The readers experience with him the failure of any attempt at closeness. The shadow of his dead younger brother Allie aggravates his sadness, and the only one he can have any connection with is his little sister Phoebe. To her, Holden confides the thematic heart of the book, his desire to be “the Catcher in the Rye”. Around her center, the most poignant passages, like the chapter where Holden goes to the Museum of Natural History, the only place where he feels at home, free from the phonies he hates, amidst reconstructions that are immobile and by definition cannot disappoint him – but in reality, they are just illusions, like the uncompromising idealism which Holden holds on to. He is as intransigent as Salinger, who withdrew from public life and remained invisible to the media for the rest of his life.

Catcher of people

Japanese critic Yasuhiro Takeuchi underlines a curious analogy between the verb catch and the verb hunt, enlightened by the Zen archery principles of master Kenzo Awa. The act of hunting in the gospel reading – Holden often brings up Jesus – can be read as a metaphor for the fisherman Peter, who thanks to Jesus manages to catch a multitude of fish, and Jesus foretells him that he will become a catcher of men. Holden’s desire, misunderstanding Robert Burns’ poem Comin’ Thro’ the Rye, is to catch children before they fall off the precipice. His desire is to find meaning in life by saving the other children who are about to fall. Phoebe, a projection of Holden’s good conscience, may confirm this theory since Phoebe is the Greek name of Artemis, goddess of hunting and protector of children.

We don’t know how many children Holden saves after the end of the book, but he managed to save himself, and maybe Salinger as well, keeping him alive through the nightmare of the Second World War.

On a more personal note

In 1994 Italian writer Alessandro Baricco founded Scuola Holden, in Turin, a school for contemporary humanities inspired by the Renaissance workshops and a revolutionary idea: to create a school from which Holden Caulfield would never be expelled. A place where even a difficult boy like him could feel understood and at home.

I studied in that school 20 years ago and there I met Professor Harold Bloom, one of my great teachers. We dedicate Hypercritic to him, with the aim of doing what criticism should do, which is turning opinion into knowledge.

Hypercritic begins its adventure today, July 11, 2020, the day Harold Bloom would have celebrated his 90th birthday.

Hypercritic’s first core editors are an international group of my students from Scuola Holden, where I teach today, and so we bring that H of Holden’s into Hypercritic.

“Don’t ever tell anybody anything. If you do you start missing everybody”, says Holden at the end of his novel.

Like him, we’ll take the risk of telling you everything.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic