Artaud | Luis Alberto Spinetta’s Rock Manifesto

Artist

Year

Country

Tracks

Runtime

Written by

Produced by

Genre

Label

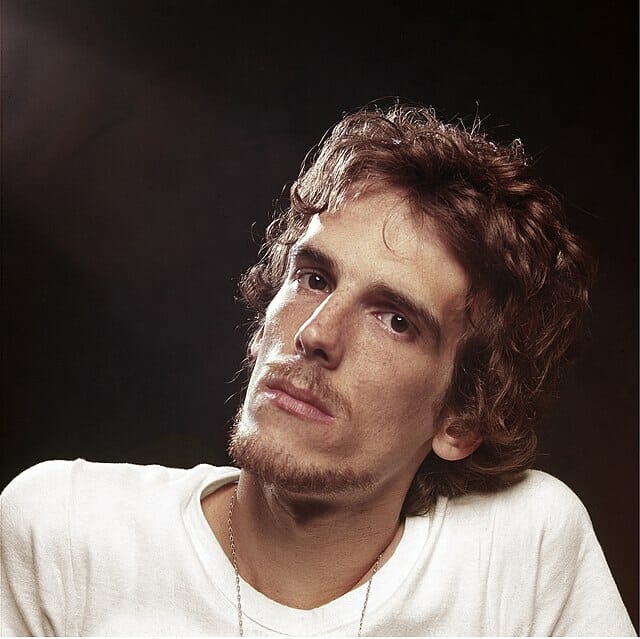

On an October evening of 1973, two weeks after the beginning of Juan Domingo Perón’s third mandate, Argentine rockers gathered in the auditorium of the Teatro Astral of Buenos Aires for the presentation of Luis Alberto Spinetta’s second solo album, Artaud. At the age of 23, Spinetta had already played in two cult bands and was one of the most influential musicians in the Argentine rock scene. But when he stepped on stage that day, it was not simply to launch his album: he wanted to make a statement. Before the beginning of the show, people in the audience received a short manifesto titled Rock: música dura. La suicidada por la sociedad (Rock: tough Music. Suicided by society). Here, after a few theoretical lines, Spinetta traced four words: rock is not dead.

Such a statement might sound odd to the contemporary reader: after all, the seventies were the golden age of rock music, or at least so it seems. But to Spinetta, things were more complicated.

Tamed and freed, freed and tamed

The early 1970s were a decisive moment in Argentina‘s history. After years of repression by the military dictatorship Revolución Argentina, the labour movement had finally gained momentum. Then, in 1973, the regime fell for good. It is in the middle of this all that Spinetta wrote the manifesto and the album.

Apart from being a musician, Spinetta was a well-read intellectual. He had strong political and artistic views, and he wanted to make them heard. The violence of Revolución Argentina’s last years is evoked in Artaud’s sixth track Cantata de puentes amarillos (Con esta sangre al rededor/no sé que puedo yo mirar/La sangre ríe idiota como esta canción…). A nine-minute-long acoustic suite, the track is not only a profound piece of social criticism. It shows off Spinetta’s composing instinct at its best. It features five major melodic changes, but the progression couldn’t sound any more natural. The lyrics are inspired by Vincent Van Gogh’s paintings and by the essays of Antonin Artaud, after whom the album is named. It is, ultimately, a hymn to madness as the only answer to society’s evils, a surrealistic tale of Argentina’s unrest.

But as an artist, Spinetta’s concerns in those days were twofold. While the political turmoil escalated, similar tensions shook the music business too. Producers, he explained in his manifesto “are no different from the company bosses who are exploiters of their workers.” Thus, as Argentina went through such a tough period, rock was running the risk of getting tamed too.

Rock music was born to open minds — to set people free — but the pursuit of fame had turned it into a career. Musicians were getting engulfed in the perverted system that some years later The Pink Floyd would describe as The Machine. They were not heralds of freedom anymore, they were becoming gears. Spinetta’s reservations on the industry resulted in the composition of La sed verdadera, an imaginary dialogue between the rockstar and a fan. On a warm, dreamy acoustic guitar base, he sings an open critique of the idolisation of musicians.

Love is the answer

But while the Machine was growing, rock was not dead: as these changes took place, Spinetta was composing Artaud. “The one who receives,” he But while the Machine was growing, rock was not dead: as these changes took place, Spinetta was composing Artaud. “The one who receives,” he wrote in the manifesto “must definitely understand that Argentine rock projects are born from an instinct”. In writing his second solo album, he was determined to let his instinct flow untamed. After two years doing hard and blues-rock with his band, Pescado Rabioso, he wanted to go for a more acoustic sound and explore the tender side of the genre, but his bandmates didn’t accept such a shift. There was no space for compromise. The album came under the name of Pescado Rabioso for legal reasons. Yet, when it was released, the band didn’t exist anymore. The point is that Spinetta had found an answer to his tribulations, and he couldn’t give up on that.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

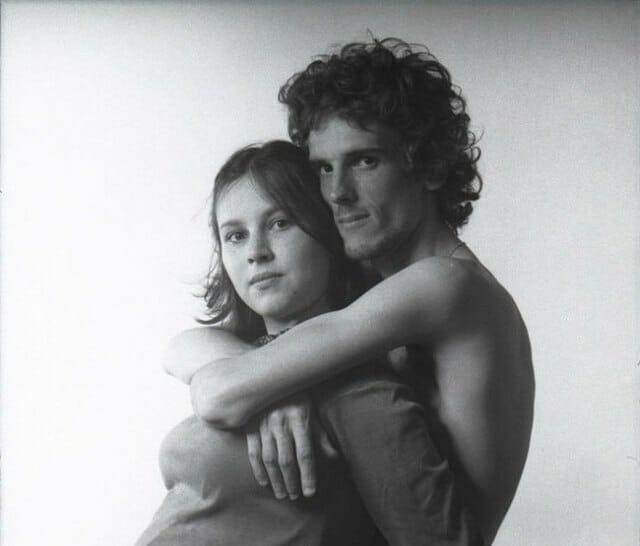

According to musical critic Claudio Kleiman, “Luis contrasted the suffering and madness of Artaud with the redemption through love advocated by Lennon.” In fact, other than the release of Artaud, there are more intimate reasons why 1973 was a crucial year for Luis Alberto. He met the love of his life, Patricia Salazár. The encounter with his soon-to-be-wife influenced his works. There is a spontaneous tenderness infusing all of the tracks, even the darkest ones: each and every one of them breaths unbounded love.

In Por, Artaud’s third track, this warmth gets even more touching. Against a gently arpeggiated guitar background, Spinetta modulates his crystal clear voice in slowly rising scales. It sounds like a lullaby, and the lyrics follow this mood. In their old Arribeños house, Luis and Patricia composed them by choosing random words that would fit in the metrics. It could be the product of a child’s mind, and here lies its beauty.

The point of it all

When Artaud came out, its value was immediately clear. Spinetta had produced one of the greatest albums in the history of rock nacional. “When I heard the album, I wanted to kill myself” said Black Amaya, Pescado Rabioso’s drummer. Years later, Rolling Stone named it the best Argentine rock album of all times, and with good reasons. Songs such as Bajan and Cementerio club were soon to become classics. But apart from its musical quality, another of Artaud’s strengths is the spirit that infuses it. According to journalist Pablo Sanchton, it’s “an aura of something unrepeatable”, the belief in music as an agent of change. That’s because, at its core, Artaud is a quest for freedom and beauty.

Years after the release of the album, Spinetta made his message clearer. “Look,” he declared in an interview, “I think nothing we do makes sense if it’s not really a global liberation of people.” The power of this message is what makes Artaud one of the essential albums of all time and a demonstration of what rock is for.

You can stream Artaud on Spotify

Tag