Pan's Labyrinth | An Antifascist Fantasy

Year

Runtime

Director

Writer

Cinematographer

Music by

Format

Genre

Spain, 1944. At the height of Franco’s regime, the daydreaming pre-teen Ofelia moves with her pregnant mother into the woods, to a Falangist outpost led by her new stepfather Vidal. While the man sadistically pursues the war against the few Maquis rebels who are left, the girl chances upon a nearby labyrinth. There, she encounters a faun who reveals to her that she is the reincarnation of an underworld princess. If she can pass three trials, he will allow her back into the magical kingdom. But she’ll soon realize that the horrors of Fascism won’t easily allow her attempts of escape, or escapism.

A Universal History of Infamy

Released in 2006, Pan’s Labyrinth is the second installment (following the horror tale The Devil’s Backbone) in Mexican film-maker Guillermo Del Toro’s uncompleted Magical Realism trilogy. The writer and director aimed to create fables for adults that intertwine his visionary approach to storytelling with the darkest side of recent Spanish history: the Francoist dictatorship. The result is an antifascist fantasy that achieves its inner balance through a constant game of contrasts.

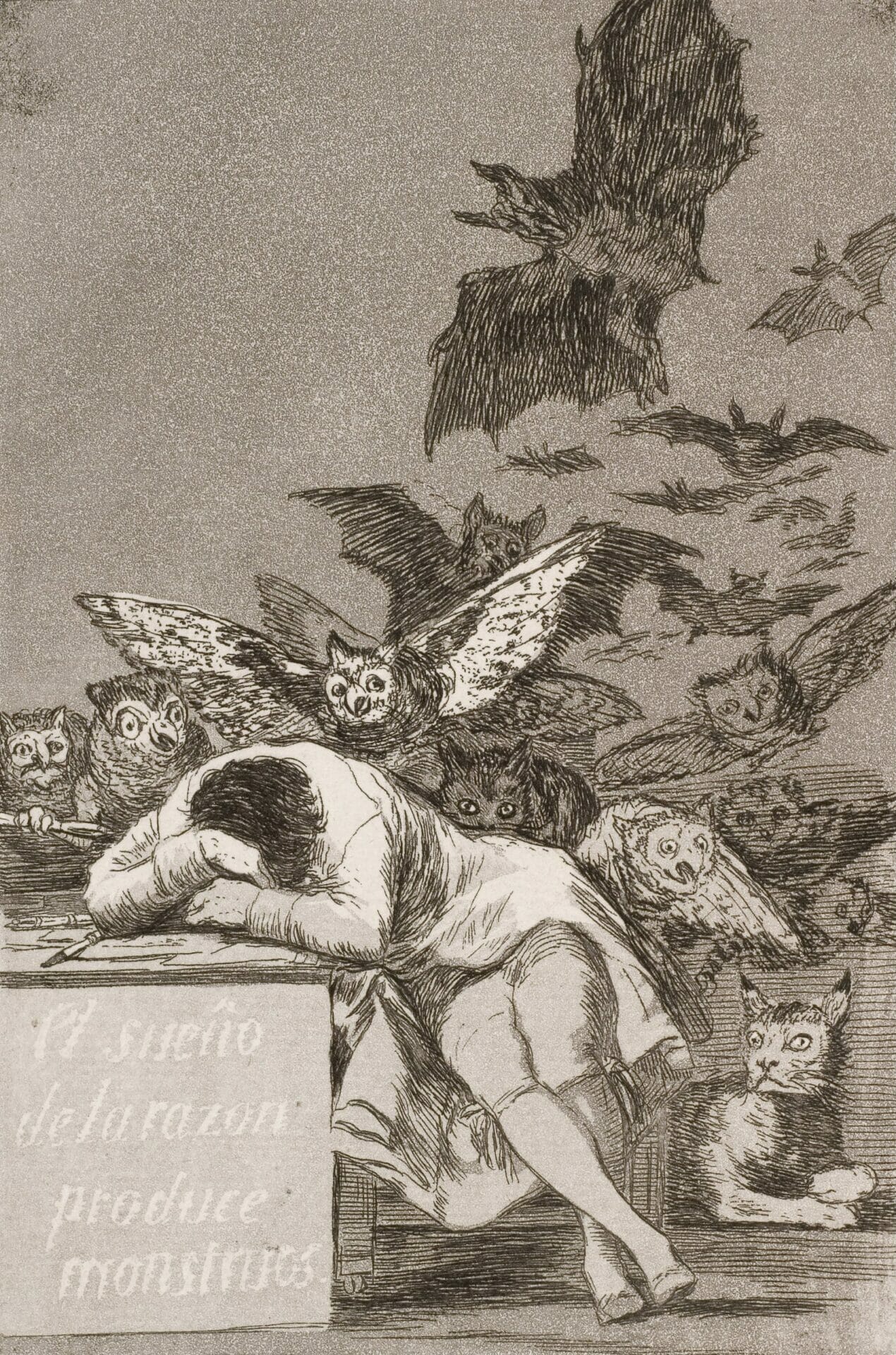

The oppositions, though, are not as facile as it seems, starting with the one between the historical and the fantastic world. The gore of the former matches the latter’s bursts of horror since fantasy elements act as a mirror distorting reality. One above all, the now-iconic “Pale Man” monster (by referencing Francisco Goya‘s painting Saturn Devouring His Son) stands as a metaphor for Spain’s history of repression. Del Toro himself tweeted that it “represents all institutional evil feeding on the helpless”, most notably (as he also claimed) Clerical Fascism.

The moral solution to authoritarianism the author offers is plain: disobedience. It’s significant that of all the mythical creatures, for the role of man on the threshold he chose a Faun. It’s not just any pagan icon. It has seen his features reassigned to the Devil, disobedience par excellence but possibly also, in a Paradise Lost fashion, ultimate freedom.

Story of the Warrior and the Captive

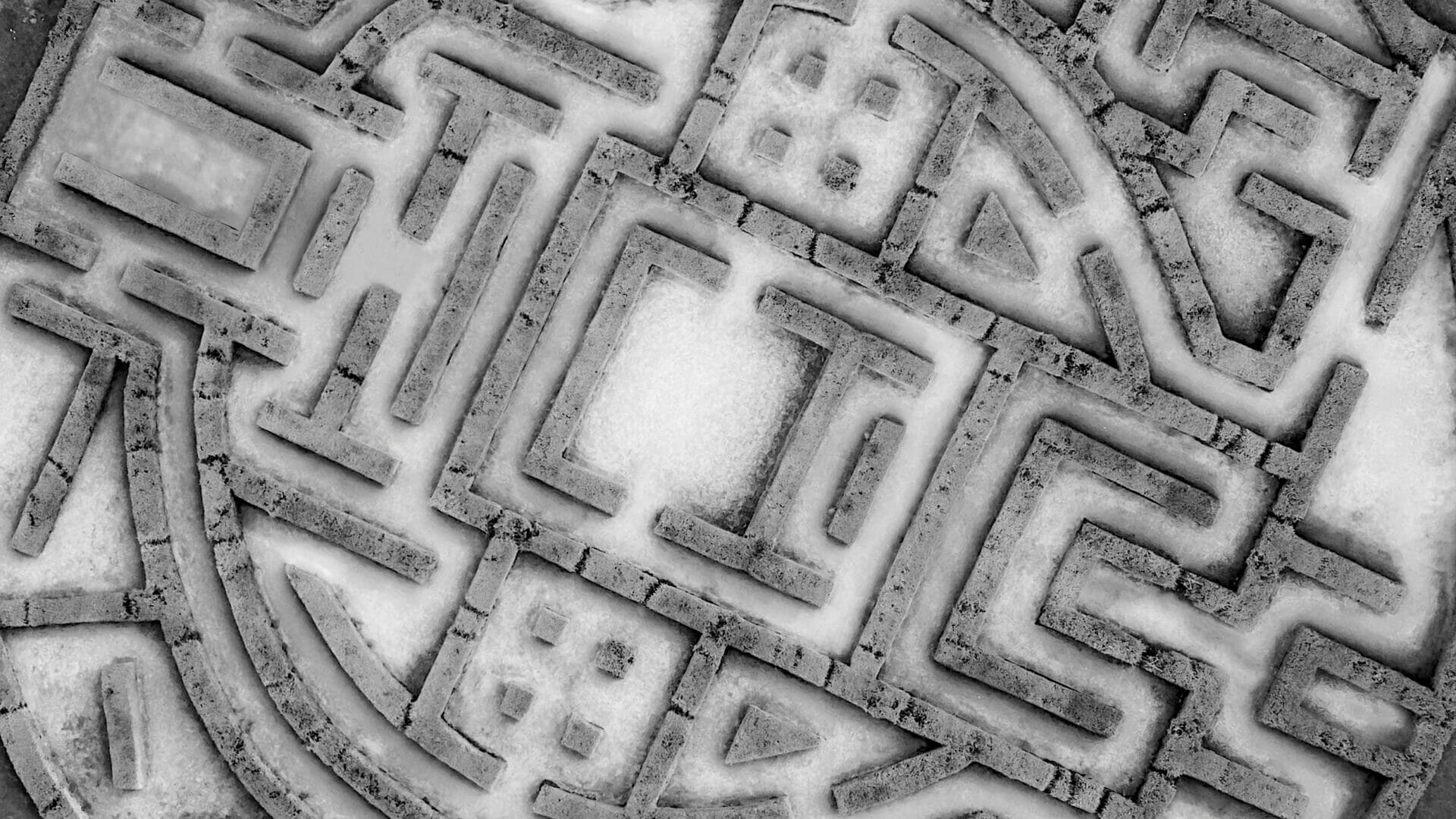

The central narrative contrast comes with opposite visual approaches. The mise-en-scène (Academy Award-winning cinematography and production design specifically) grounds the real world in cold colors and sharp geometries while picturing the fantastic one with warm hues and round shapes. This stylistic choice goes along with the other fundamental contrast that pivots around gender.

On the run from her stepfather’s male-dominated world, Ofelia finds shelter in a universe admittedly designed around feminine archetypes, as the uterine tree featured in the playbill shows. But what at first might seem like a return to the mother’s womb is actually a rite of passage. Through the trials, the heroine will grow into a woman capable of selflessness and ultimately, self-determination. Conversely, Vidal will find his patriarchal tenets – honorable death and male lineage – severely questioned by the maze. In the end, Pan’s Labyrinth is not only an antifascist fantasy. It’s also an antifascist coming-of-age.

The Two Kings and the Two Labyrinths

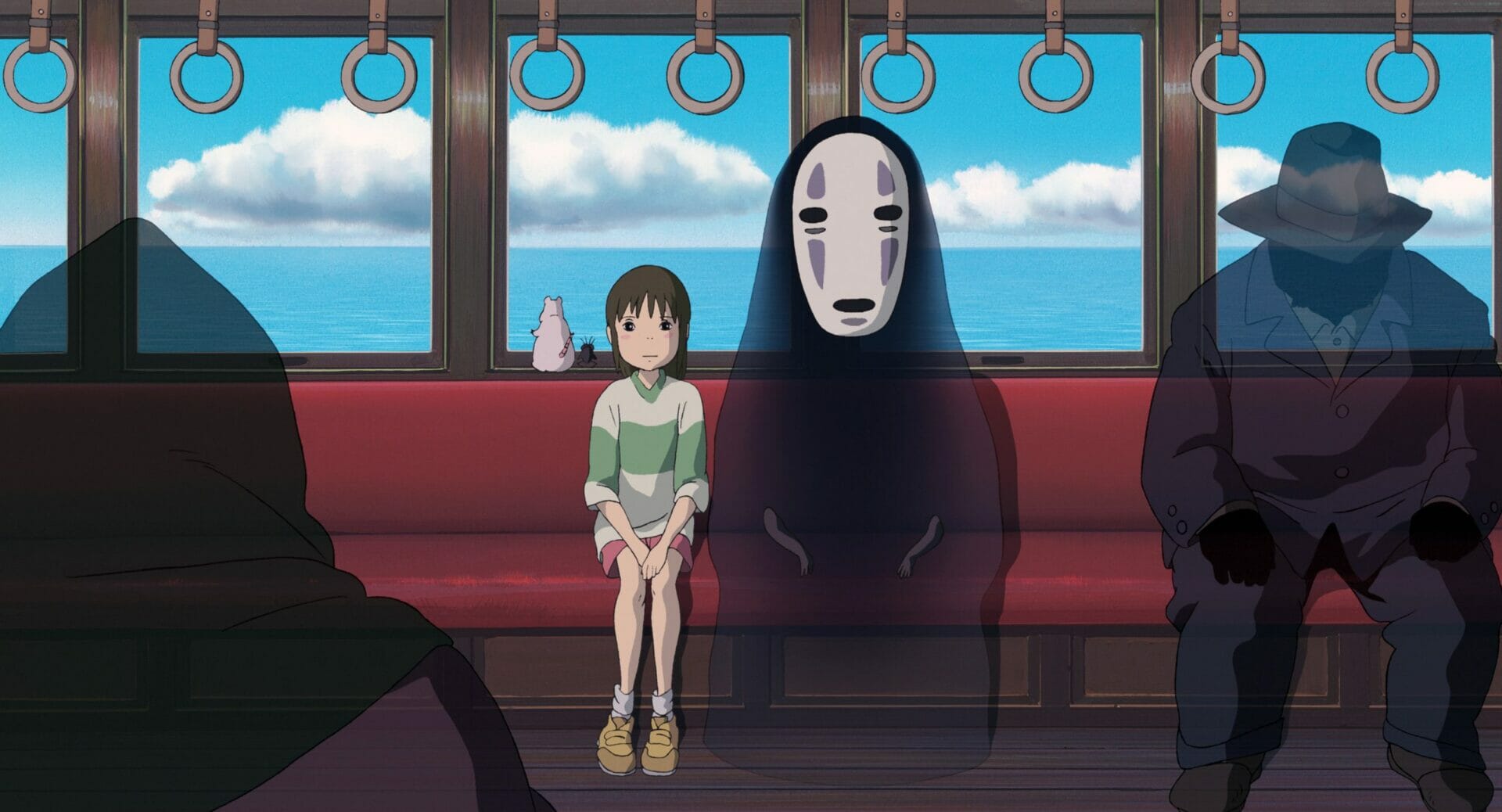

Pan’s Labyrinth juxtaposes its two kingdoms with such strength, that it begs the question as to whether the Faun and his underworld are just the heroine’s brainchildren. The overall oniric tone reinforces the doubt: after all, the soundtrack’s main theme is a lullaby. Not to mention the fact that Ofelia bears the name of Hamlet‘s fiancée, another victim of events and illusions. There is, though, a second source of disbelief.

It lies in the contrasting aims of the movie, as it simultaneously engages the viewer in the narrative and calls attention to itself through homages. The script is riddled with references to other archetypical stories. Among all, the choice of setting evokes Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of Stephen King‘s The Shining and cult fantasy flick Labyrinth. The other, and primary, name that comes to mind is Jorge Luis Borges‘, one of Del Toro’s favorite authors. The Argentinean writer built his whole corpus upon mazes, as well as on self-awareness. In his works, the literary labyrinth stands for both the labyrinth that is reality, and the endeavor to reflect on such incomprehensibility through fiction.

Del Toro embraces Borges’ suggestions and takes them a step further. He made it clear when he called this already antifascist fantasy “a Rorschach test of where people stand”. Whether the underworld exists is not decisive. What’s decisive is what the viewers choose to believe in, and whether they acknowledge it. The enjoyment of Pan’s Labyrinth doesn’t just lie in losing oneself within all its forking paths. It also comes from finding oneself again.

Tag