Calvin and Hobbes at 40 (analysis) | A Tribute to Bill Watterson’s Imaginative World

Author

Year

Format

Genre

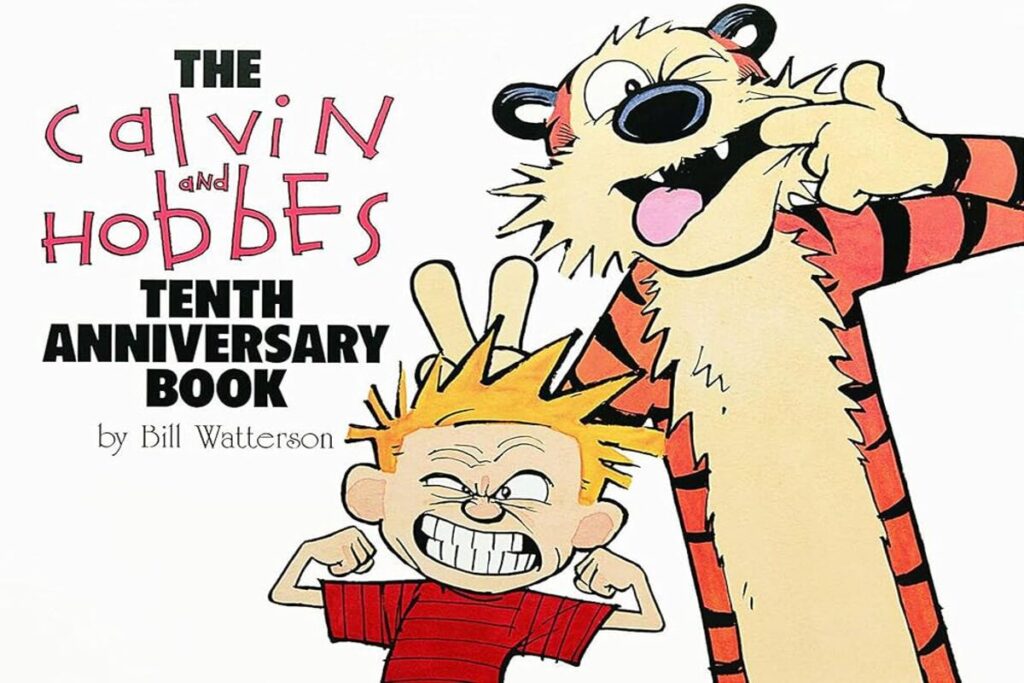

During the first year of publishing, Bill Watterson dabbled in different ideas for what Calvin and Hobbes could be. However, the base concept was sound: the adventures of six-year-old Calvin and his best friend Hobbes, an anthropomorphic tiger whom everyone else sees as a stuffed toy. The comic strip debuted in November 1985, distributed by Universal Press Syndicate, and featured in newspapers for 10 years. With its lighthearted, insightful touch, it conveyed the endearing familiarity of the two characters and the unexpected, wondrous scenarios that lay beneath the surface of everyday life.

No duo like a boy and his tiger

Calvin is a multifaceted character, never intended to be solely the mischievous kid trope. Most of all, he is a channel for his creator to explore a wide range of topics: from discussing human nature to experiencing the unrestrained fun of childhood; from indulging in fantasies populated by dinosaurs to discussing morality while on a wild wagon ride. Calvin and Hobbes manage to achieve this balance of themes because Calvin himself is a cohesive protagonist. Childish yet profound, troublemaker yet good-natured, none of these themes feel out of place when expressed through his curiosity.

On the other hand, there’s Hobbes, inspired by the author’s cat Sprite. Like a faithful feline, he is pensive, dignified, and proud – a perfect match for its rowdy counterpart. He is in equal parts the voice of conscience and accomplice, always at Calvin’s side. His character walks the line between an imaginary friend and a plush toy that comes to life. However, Watterson was never interested in clarifying his nature, being deliberately vague about it. Hobbes represents a brilliant example of subjective reality. Every person sees the world differently – Calvin more than anyone else – and Hobbes personifies this phenomenon. The two share a genuine friendship, based on loyalty and affection, despite the occasional squabbles.

Calvin and Hobbes is all about the power of imagination

Calvin’s imagination represents the heart of the comic. It is also the reason why the strip could feature so many different scenarios without ever feeling repetitive or forced. Thanks to his creativity, Calvin can make cardboard boxes into grandiose inventions that allow him to travel back in time, create clones, or transform himself.

He also has various personas, each representing a glimpse into a different world. Like Spaceman Spiff, a cosmonaut exploring alien worlds, the superhero Stupendous Man, or the noir private eye Tracer Bullet. Then there are monsters under the bed, and snowmen came to life—games of Calvinball to play and babysitters to defeat. In the strip, the mundane becomes fantastic, allowing the reader to tag along for the adventure, like in the Italian comic Monster Allergy.

Through Calvin and Hobbes, the audience experiences a childhood that is not seen through the nostalgia-tinted lenses of an adult. Instead, it is lived from the very perspective of a kid, including all its ups and downs, from never-ending school days to senseless adult rules to abide by. But also carefree summer days spent playing outside, making forts, and coming up with countless new games. It is a faithful portrait of what it means to be a child, to which everyone can relate to some extent.

Revolutionising Sunday Strips

Until the 1940s, comic strips would often receive a full page in newspapers, allowing cartoonists considerable artistic freedom with their work. However, over the years, that space was reduced, and by the 90s, Sunday strips had to follow strict rules. Their layout could be altered by newspapers depending on the space availability, sometimes even by eliminating some of the panels. And so, like many other comic artists, Bill Watterson had to learn to work with such limitations.

One such example was using the first two panels, which were at risk of being cut, for throw-away gags. This choice, while a waste of precious space, did not hinder the meaning of the strip. But as Calvin and Hobbes’ narrative grew more complex, these layout restrictions risked compromising its vision.

Most notably, in May 1991, Watterson took an unprecedented year-long break from comic work. At this time, he created a renewed layout consisting of half a page without any frame restrictions, which he proposed upon his return in February 1992. Thanks to Calvin and Hobbes‘ popularity, he was able to convince most newspapers to accept the change. This gave him the freedom to experiment with panels of different shapes and sizes, while also trying new styles and rhythms.

He was thus able to elevate the quality of his stories both narratively and visually. The use of vivid palettes, detailed backgrounds, and unconventional perspectives is a testament to this newfound artistic liberty. It also provided the opportunity to try silent comics, as the illustrations could now convey meaning without the need for dialogue—a narrative technique also employed by Krystal Kung in her graphic novel, The Little Drifter.

Bill Watterson’s refusal of capitalization

As the popularity of Calvin and Hobbes grew, so did the demand for merchandise. It was a common step for popular strips. One that still applies to superhero comics like Spider-Man and Batman, just like it did to Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts and Jim Davis‘s Garfield.

Both artists made millions from revenues alone, as their characters featured everywhere from toys to movies and video games. Schulz in particular had been one of Watterson’s primary inspirations, along with strips such as Pogo and Krazy Kat. These works had helped him understand the emotional resonance that comics could have, incorporating existential themes that went beyond mere gags. As such, Watterson chose to focus on his stories, uninterested in profiting from his art.

Despite the pressure from the syndicate, he refused to give in to licensing, believing that it would compromise the creation’s message. His refusal led to years of debates with the Universal Press Syndicate; only in 1991 would he obtain the rights to his comics and licensing, on the threat of quitting. It was a gamble, as Universal Press Syndicate held the rights and could have had another author draw the strip instead. But the syndicate had to relent upon realising that there would be no Calvin and Hobbes without Bill Watterson.

The legacy of Calvin and Hobbes

Worn out from both the dispute and having his work tied to restrictions and deadlines, in 1994, Watterson decided that it was time for Calvin and Hobbes to come to an end. Believing he had achieved all he wanted with the comic, he chose to leave his characters at their best, rather than running them out to respond to the demands of his publishers. By doing so, he stayed true to his wish to preserve the world he had created, prioritising art over commercialisation.

This artistic integrity contributed to the place that Calvin and Hobbes holds today, both in the comic world and in the collective memory of its readers. Strips that allow readers to both reflect on and laugh at themselves, appreciating the value of childhood and everyday moments, revealing the truth of being human. And Watterson’s work is among them. Featuring in over 2,400 newspapers worldwide, Calvin and Hobbes succeeded not only in sharing its values but also in keeping them alive for well over a decade of its run.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic