Post Office is like life itself: a mean, dirty, boring spot

Author

Year

Format

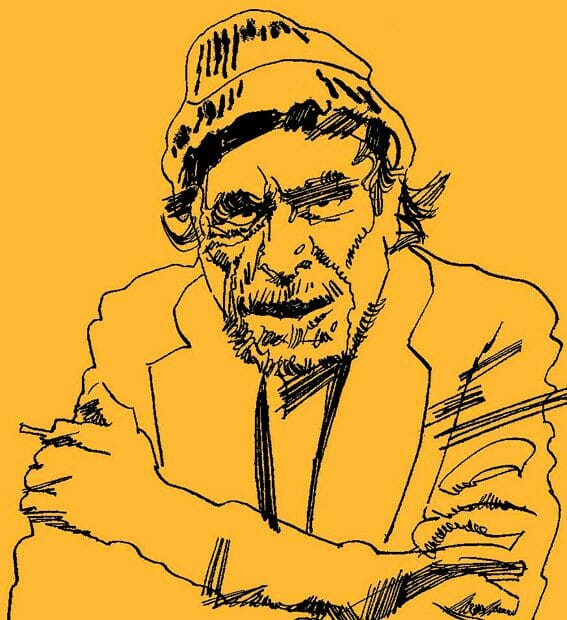

Drink, fuck, drag lazily from one day to the next, sleeping poorly and badly, betting at horse races, trying in every way to lose his post office job. The first pages of Charles Bukowski’s Post Office throw the reader – in medias res – into this routine-not-so-routine, among write-ups, millionaire women, hippies, and parakeets. Henri Chinaski, Bukowski’s alter ego, is the literary gimmick that allows a blurred journey between fantasy and reality, truth and plausibility of what B.’s life must have been like.

Between fantasy and reality

Indeed, Post Office is like life itself: a mean, dirty, boring spot. On one side stands the idealization of job security, on the other real life’s brutality and dreariness; in between, the anarchic anger of Chinaski-Bukowski, his language full of cynicism, self-mockery, and bitterness, punctuated with rare images of tenderness.

Bukowski is a Barfly (like the title of the movie he scripted) who balances the perversity of city life with alcohol and a heavy dose of cursing. The novel, an antithesis to the American dream – as in Pleasantville or The Pursuit of Happiness – is a disrespectful twist on days repeating themselves until Chinaski loses his job: and finally, reversing perspective, the novel ends and Chinaski-Bukowski starts writing.

Dirty realism and alcoholic despair

Despite the setting in the suburbs of Los Angeles, Post Office doesn’t fully explore the lives of the oppressed or marginalized – it doesn’t have the characteristics of a sociological novel. Rather, it’s a long, out-of-tune chant, a succession of scenes of dirty realism and alcoholic despair.

Like the poems and in contrast to his later novels, more monotonous, in Post Office, Bukowski combines disenchantment with a set of jokes and quips. He surprises the reader with an uncaring tone, living in the moment and recounting the art of making ends meet so convincingly to make his path tempting.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic