Nickel Boys by RaMell Ross Portrays Racism Like Never Before

Year

Runtime

Director

Cinematographer

Production Designer

Country

Format

Genre

Between the stately biographical tales of The Brutalist and A Complete Unknown and Demi Moore‘s striking performance in The Substance, some have put all their chips on experimental filmmaking for the 97th Academy Awards. Nickel Boys, nominated in the Best Picture and Best Adapted Screenplay categories, is a visual translation of American novelist Colson Whitehead‘s novel of the same name, which won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction (this is Whitehead’s second win after The Underground Railroad in 2017). RaMell Ross, in his second turn behind the camera, crafted one of the most distinctive and immersive visual experiences of the past awards season. The film premiered at the 51st Telluride Film Festival and is now available to stream on Amazon Prime Video.

Nickel Boys tells a fictional story inspired by real-life events. It unfolds against the backdrop of racial segregation that plagued the southern states of America until six decades ago. Shot from the first-person point of view of two black teenagers who meet at a reform school, the film uses inspired cinematography and filmmaking techniques to address racism with unprecedented incisiveness and empathy. Defined by Robert Daniels as “a clear masterpiece held together by visual splendor and idiosyncratic performances,” Nickel Boys reveals the deep and systemic roots of inequality and racism in American society and the recurrence of patterns and schemes that seem only distant in time.

- Being a Black Kid in 1960s Florida

- A “Sentient Perspective” on the Jim Crow Era

- First-Person POV as a Political Statement

- The Two Opposing Worldviews in Nickel Boys

- Social Divide Between Past and Present

Being a Black Kid in 1960s Florida

Elwood Curtis (played by Ethan Cole Sharp as young Elwood, Ethan Herisse, and Daveed Diggs as adult Elwood, respectively) is an African-American teenager living with his grandmother (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor) in Tallahassee, Florida. The year is 1962, and the southern United States is not an easy place to live for people of color due to systemic segregation enforced by Jim Crow laws. Elwood, however, is a brilliant kid. Encouraged by one of his teachers, he makes it into an accelerated study program at a black college. Everything seems to point to a bright future until one day, on his way to class, the boy gets accidentally involved in a carjacking. As a minor, Elwood is sent to the Nickel Academy, a notorious reform school.

A fervent advocate of civil rights, he believes he won’t be there long and expects to be released soon for good behavior. But what awaits him is worse than he realizes. Black students live in incredibly squalid conditions, face constant harassment, and engage in strenuous activities. The only support Elwood finds at Nickel is Turner (Brandon Wilson), a boy who doesn’t believe in the school reform system. According to him, escape is the only way out of the Academy. Elwood and Turner strengthen each other in their hardships and look forward to regaining their freedom.

A “Sentient Perspective” on the Jim Crow Era

Watching Nickel Boys can be disorienting for the first few minutes. Today’s moviegoers are accustomed to fluid shots and steady camerawork, making it easy to understand the development of the plot through a more neutral and omniscient third-person perspective. By opting for a subjective point of view, alternating between Elwood and Turner, RaMell Ross breaks this detachment and erases the space between the characters and the audience. Viewers see the narrative world as if the camera were in the boys’ eyes: the camerawork mirrors their gait and head movements, creating the unusual feeling of a Minecraft-style role-playing video game.

This choice implied the substantial use of both long takes and quick cuts of fragmented details during editing and the choice of a subtle yet incisive ambient sound to enhance the characters’ sensitivity. The movie editor, Nicholas Monsour, revealed that the technical professionals involved in the production had frequent chats with the writers, so everyone was on the same page. This formal approach echoes the director’s big-screen debut, Hale County This Morning, This Evening, which triumphed at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival. Ross spoke at length about such an unconventional stylistic choice in a video interview for IndieWire, calling it a “sentient perspective” and citing the need for the viewers to identify with the protagonists fully.

One idea Joslyn [Barnes, the film’s co-writer, e.d.] and I talked about earlier in the writing process was: what if Elwood and Turner had their own cameras to document their own lives at the time? There’s not much visual poetry from black folks’ perspective that exists in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, at least popularly shared. And so, what was their life like from their eyes?

Director RaMell Ross

First-Person POV as a Political Statement

In Kathryn Stockett’s novel The Help, also set in the 60s Deep South, black characters express themselves in colloquial African-American slang to enhance readers’ empathy with their stories. Similarly, Nickel Boys portrays “the horrors of the Jim Crow era as its victims would have observed it.” The audience is inside Elwood’s head as he enters Nickel Academy for the first time in a police van and takes his first shower, squeezed between the wet bodies of other students. You can almost feel the breeze on the boy’s hand as it reaches for the sky, or even sniff the sharp smell of paint as he paints a porch.

Focusing on these life fragments, made of simple moments and repetitive movements, creates a holistic sensory experience, stimulating unprecedented engagement. This aesthetic approach is quite the opposite of the recent Netflix success, Adolescence, where the temporal continuity resulting from the exclusive use of long takes enhances the empathy with the protagonists. Both shows, though, leverage a technical solution to tell stories of teenage years as a crucial moment of individual transformation and shaping of political consciousness.

Subjective perspective is a stylistic choice and a peremptory political statement. The sensory coincidence between viewers and characters holds the strength of a metaphor for the universality of systemic racism. The film forces viewers to experience the entire story from the perspective of historically oppressed bodies, suggesting in subtext that systemic racism is not an external problem but an issue that affects everyone. Countless books, films, and artworks have depicted racism from the outside, enabling people to observe it. However, the movie takes a step further: the audience can feel and embody it this time.

The Two Opposing Worldviews in Nickel Boys

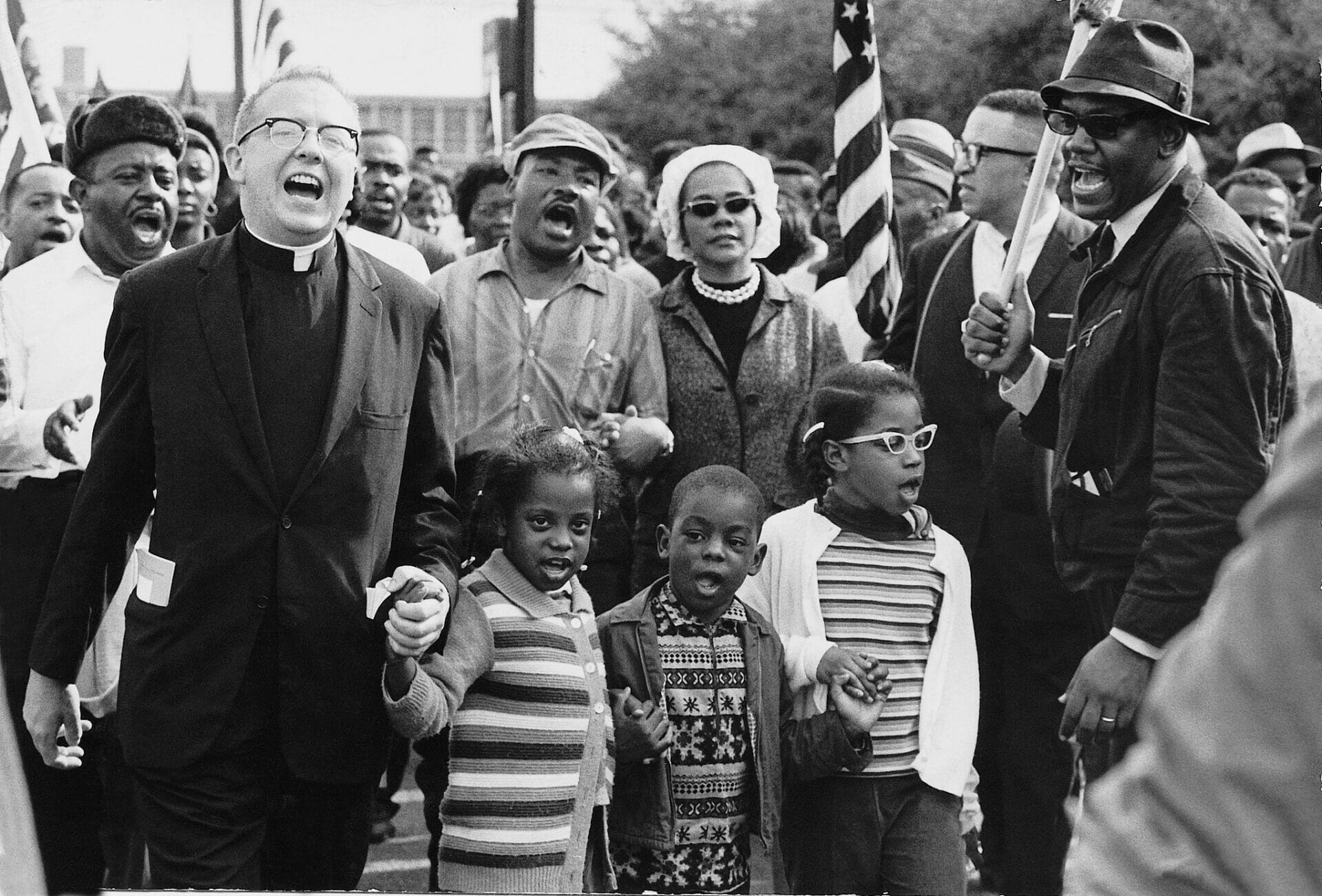

The viewer does not get a clear view of the main character for the film’s first half hour. Elwood’s face appears fleetingly in reflections on buses and shop windows. However, what the character does see perfectly expresses his personality with few but simple images. He is a hopeful and joyful child with an analytical view of the world around him. When the camera adopts his perspective, it transmits many extreme close-ups, small details, and gestures – a knife crawling over the edge of a plate, a marble rolling down a staircase – that suggest his vibrant curiosity. In addition, the many archival shots of Martin Luther King and Sidney Poitier films express his strong idealism and substantial optimism for his and other black people’s futures.

On the contrary, Turner lacks his friend’s positive attitude. He has been at the Nickel Academy long enough to understand that all the vaunted goals of re-education are a dead end, no matter how good the students’ intentions. His experiences there have left him with a cynical and disillusioned view of the world, content to mind his own business and ignore the fate of his fellow man. Things change when Elwood joins the Academy. He is the only one who can break through Turner’s armor and gain his trust. Eventually, their friendship helps them understand each other and bring their previously opposing visions closer together.

Social Divide Between Past and Present

Racism has always been a central theme in Colson Whitehead‘s literary output. In Nickel Boys, the author presents an unprecedentedly vivid version of the phenomenon, inspired by a real-life case study: the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys in Florida. Despite its already notorious reputation, it was only in the early 2000s that in-depth investigations revealed the shocking truth of ongoing abuse, torture, and even murder, with the discovery of over 50 student bodies on the reform school grounds.

While watching Ross’ film, viewers uncover these horrors along with the adult Elwood, who scans the Internet for news of the investigation into the former Nickel Academy. From time to time, the film also shows archival footage purporting to show former students of the real Dozier School. They are a harsh reminder of the historical reality of the Jim Crow era, which, while reminiscent of 19th-century slavery, is as recent as the 1961 Apollo 11 moon landing, an essential symbol of progress and modernity that the film also references through archival footage.

At Nickel Academy, whose structure mimics that of plantations, there is a sharp segregation between white and black students, with the latter receiving far worse treatment. This inequality, however, seems to persist to this day and is a crucial issue in the debate on education. Indeed, the division of the American territory into strictly segregated school districts creates a vicious cycle in which youth from poorer and usually more multi-ethnic neighborhoods are forced to attend less prestigious and less well-funded schools. Nickel Boys aims to shed light on these troubling histories, to express the systemic and inherent nature of racial discrimination in the U.S., and to remind us that the road to an inclusive society is still a long one.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic