No Ordinary Sun | An invocation to surrender

Author

Format

Length

By

First published in 1959 in the New Zealander magazine Te Ao Hou, No Ordinary Sun is one of the best-known instances of nuclear critique in poetry. Hone Tuwhare, its author, was a Māori New Zealand poet. He gained recognition thanks to his first collection of poetry, named after his 1959 poem. Together with other Oceanian activists and writers, such as Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner and Déwé Gorodé, his poems have contributed to shedding light on nuclear experimentation in the Pacific Ocean.

After No Ordinary Sun, Tuwhare published several volumes of poetry, some short stories, and plays. One of the defining characteristics of his poetry is its rhythm and its ability to conjure up emotions and images. It is possible to hear a few of his poems online, thanks to recordings made some years prior to his death.

Beyond the metaphor

No Ordinary Sun does not directly mention the atomic bomb. In spite of that, the images the lines evoke and the sun metaphor are unmistakable references. In 1964, U.S. nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands had just stopped, and the nuclearisation of the Pacific Ocean was not over. Likening atomic explosions to the rise of a new, monstrous sun was not an uncommon trope.

However, Tuwhare actually negates this solar metaphor by showing that there is nothing natural about atomic bombs. Starting from the title, which includes a negation, all five stanzas are built to signal the unnaturalness and the catastrophic consequences of this man-made weapon.

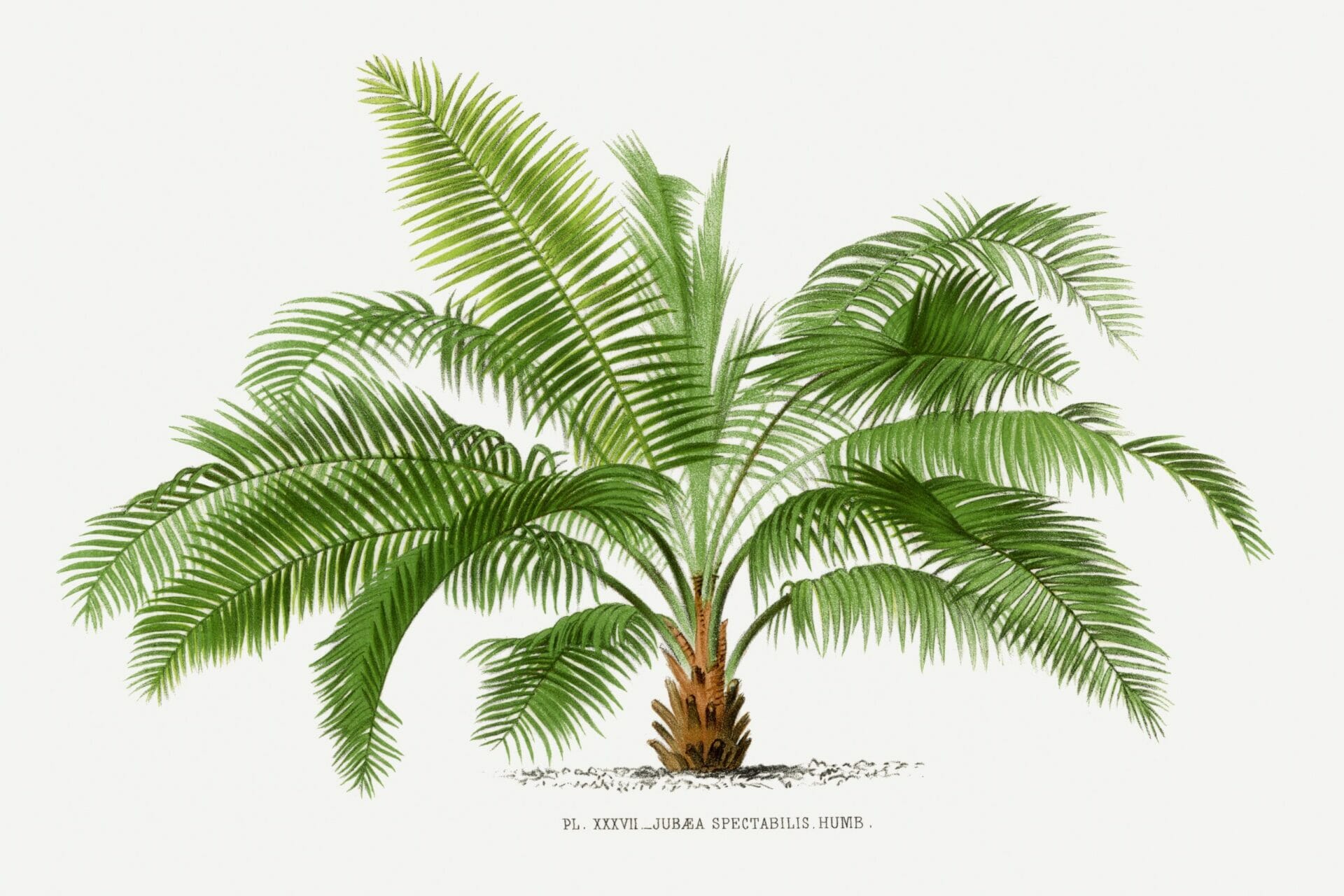

Tree let your arms fall:

raise them not sharply in supplication

to the bright enhaloed cloud.

Let your arms lack toughness and

resilience for this is no mere axe

to blunt nor fire to smother.

The effect of these repeated negations is that of a warning for the personified tree, not to mistake the bright enhaloed cloud for the life-giving sun. Thus, the negation of the solar metaphor works as a reminder: nuclear disasters, as shown by the HBO series Chernobyl, are not the consequence of a supra-human power but of humans alone.

About monstrosity

The word sun appears for the first time in the middle of the poem, in the third stanza, qualified by the adjective monstrous. Here, the tree takes on a new role: if previously it stood as a symbol of the natural world at large, now it turns into an ineffective shelter against the power of the bomb.

Your former shagginess shall not be

wreathed with the delightful flight

of birds nor shield

nor cool the ardour of unheeding

lovers from the monstrous sun.

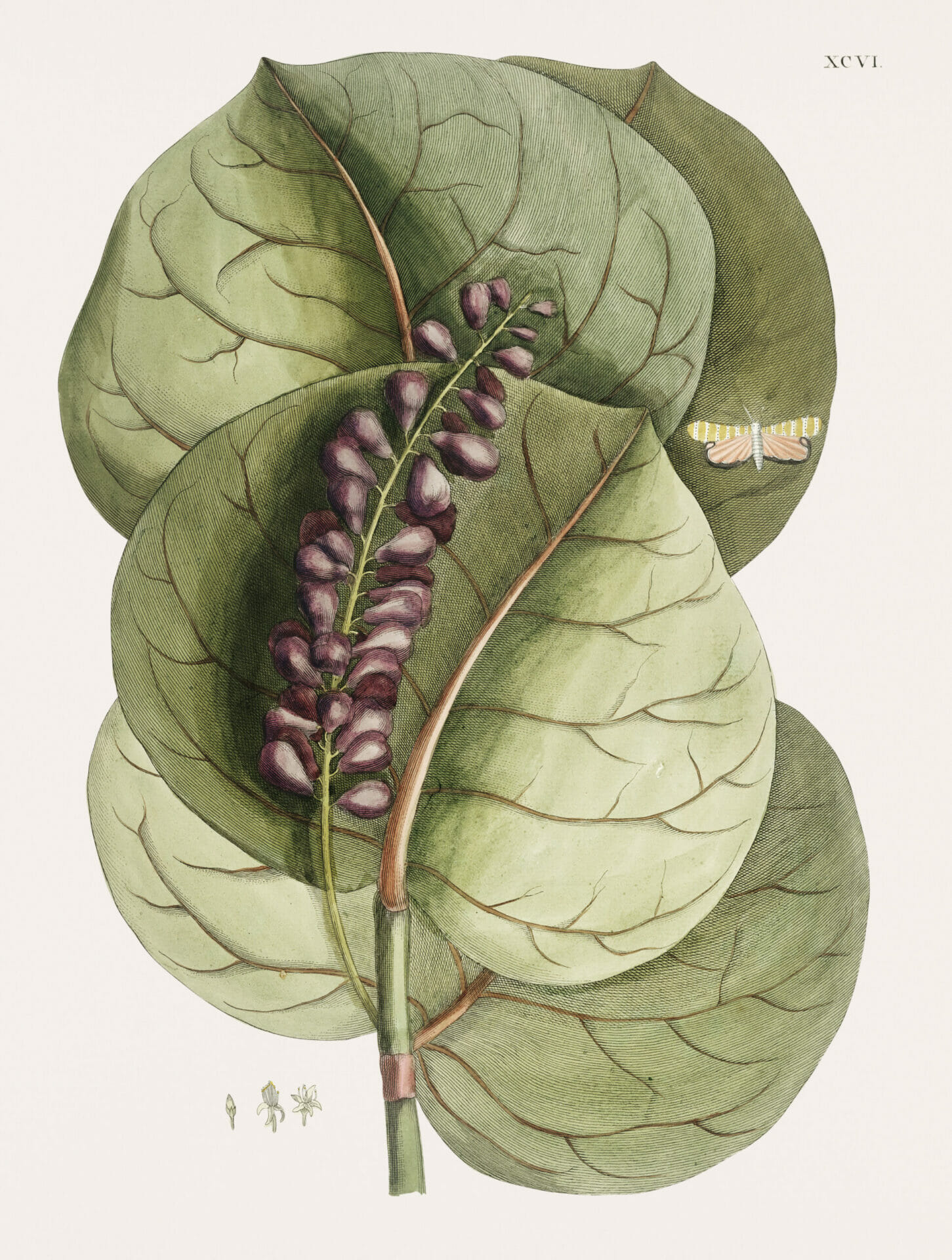

The sun is monstrous because instead of giving life, it takes it away: the helpless tree cannot but surrender to catastrophe and acknowledge that it cannot fight the spreading pollution. The explosion thus reverses the natural life cycle, whereby solar radiation enables trees to capture CO2 and input oxygen into the atmosphere. Here, by contrast, the tree fails to purify the corrupted and sunless air.

Throughout the poem, Tuwhare clearly plays with words, too: emanation, radiation, and radiant ball, for instance, resonate with double meanings. They both refer to natural processes and their opposite, nuclear blasts.

A spectral landscape

As if in a crescendo of catastrophe, the last stanza depicts the tree as entirely lifeless. It begins with an apostrophe, but the invocation is hollow. The landscape is empty, and nothing is left to transform. Only death remains, signaling the end of the tree’s life and all it stood for. The monstrous sun has also deprived life of color: the mountains are shadowless, the plains are white, and the sea floor is drab.

O tree

in the shadowless mountains

the white plains and

the drab sea floor

your end at last is written.

No Ordinary Sun is a denunciation of the havoc provoked by nuclear experiments and of their consequences on both human and more-than-human beings. Tuwhare manages to convey a sense of dismay and terror through his use of reiterations and evocative language. Like Emily Dickinson accompanies her readers through a journey with Death in Because I Could Not Stop For Death, the Maori poet shows what such a journey could look like in real life.

Tag