John Keats' To Autumn | The rhythm of fading light

Author

Year

Format

Original language

Genre

By

Many poets, from Shakespeare to Verlaine, from García Lorca to Carducci, have sung about the beauty and the mystery that surround the passage from summer to winter. John Keats is perhaps one of the best-known: his lyrical stanzas are both finely crafted depictions of nature and deep meditations on life. To Autumn not only exemplifies Keats’ style but also his poetic legacy, being the last poem he wrote.

Keats had indeed a short life, characterized by early experiences of loss and mourning, and punctuated by illness. He died of tuberculosis in 1821, when he was only 25 years of age. In spite of his premature death, he is considered one of the most representative Romantic poets, alongside Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron.

To Autumn was written in 1819, and was the last of a series of odes published in that year, such as Ode to Psyche and On a Grecian Urn. Autumn’s soft hues, gentle motions, and mellow sounds are portrayed delicately, showing how beauty can be found even when decline approaches.

An illusion of summer

To Autumn is divided into three stanzas, which together depict the progressive passage from summer’s late warmth to the approach of winter. In this way, the first eleven lines describe autumn as a season still animated by light and life. Trees bend with the weight of apples, vines decorate cottage roofs, hazelnuts fill their shell, and late flowers trick bees into dreaming of a never-ending summer:

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

To Autumn, lines 1-11.

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss’d cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For Summer has o’er-brimm’d their clammy cells.

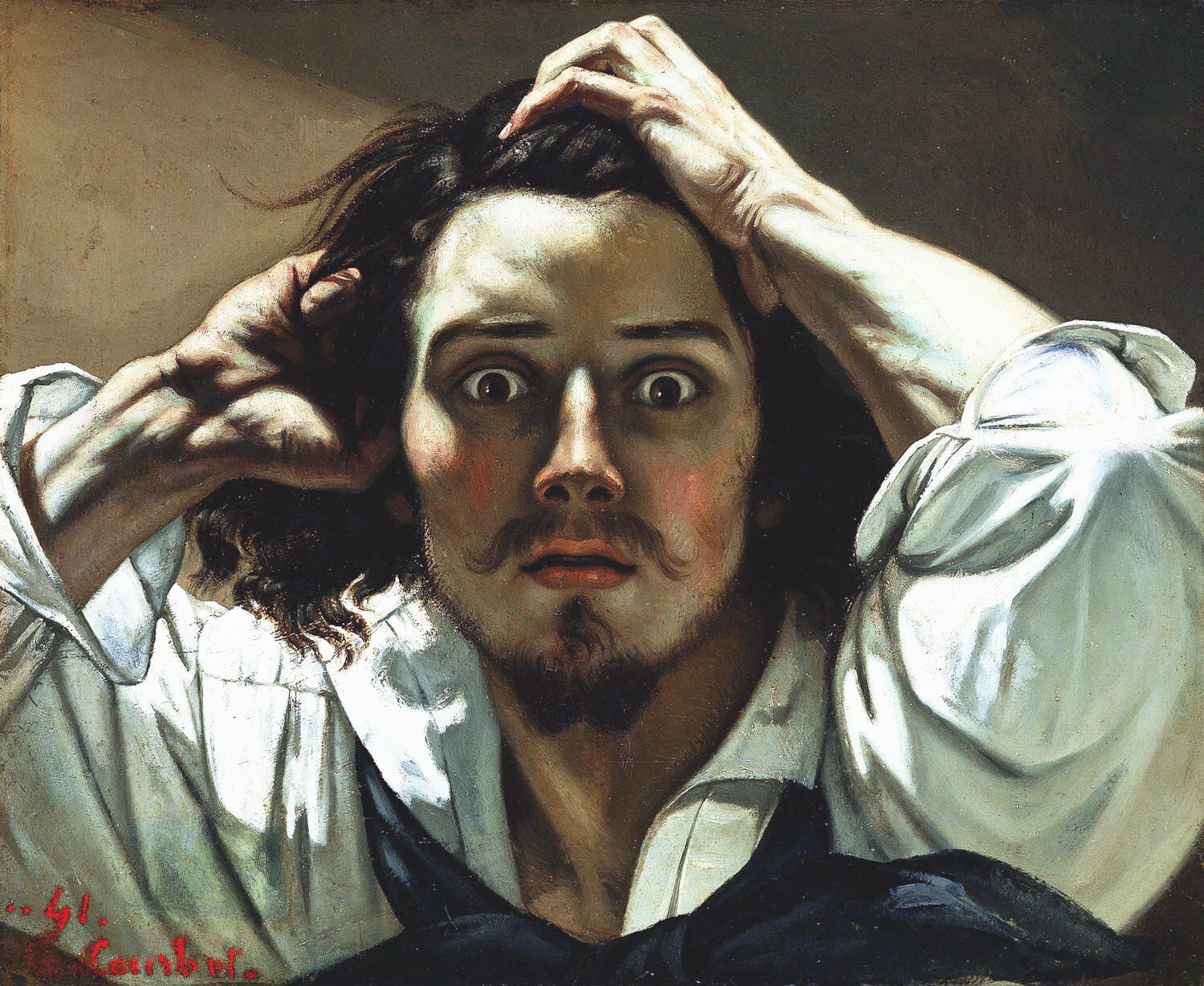

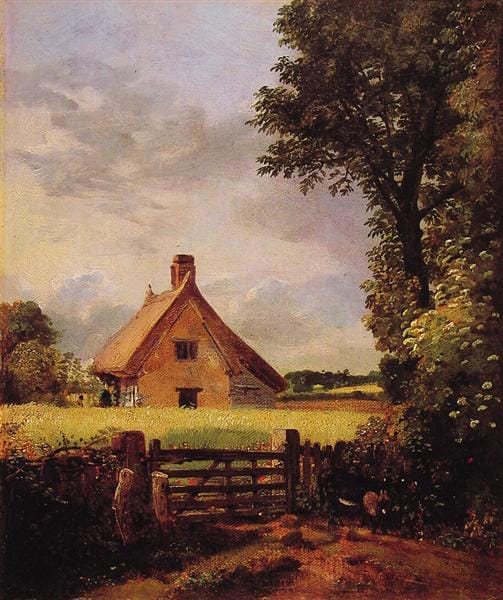

Both the sun and autumn are personified, a choice that makes the poem resemble an intimate conversation between the poet and the natural elements, which conspire together to make warmth and fruitfulness last. The warmth emanating from this scene recalls that of paintings by some of Keats’ contemporaries, such as John Constable’s A Cottage in a Cornfield.

Autumn as an agent in the natural world

The personification of autumn continues in the second and third stanzas, where it becomes clear that the season is more than an object of meditation: it is a real agent in the natural world. By sitting on a granary floor, or sleeping amongst fields, Autumn suffuses its surroundings with a sense of drowsiness and slowness. It is a moment to contemplate and to patiently look at the cider press or watch the stream flow.

The final stanza brings readers farther from spring but with the acknowledgment that, like spring, autumn has its own rhythm too. These last lines are still brimming with life – lambs, swallows, and crickets all animate them – but the colors seem less bright, and the day slowly fades into the night.

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

To Autumn, lines 23-33.

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,—

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

The soft-dying day

Critics have given different interpretations of this poem, but all agree on a point: it is more than a depiction of autumn. As The New York Times points out, the melancholy that tinges its last stanzas is to correlate with Keats’ personal life. In 1819, when he composed the poem, his health was fast declining, a fact that forced him to put an end to his poetic endeavors. His characterization of Autumn as “Drows’d with the fume of poppies” could mirror his own experiences with opium which, at the time, was a common painkiller.

In spite of providing the poem with a possible background, pain, and illness do not pervade its lines. Keats’ poetic force also transpires from this: his ability to touch on the bitter and troubling side of human life on Earth, but using a language that is suffused with warmth and music.

Tag