For the first time, comics took over the entire Centre Pompidou in Paris, for a little more than five months. With “La BD à tous les étages” (Comics on every floor), the museum hosted a series of events and exhibitions where comics got center stage from May 29th to November 4th. The so-called Ninth Art was examined and celebrated from multiple perspectives thanks to, among the other initiatives, an exhibition on a sixty years span of comics and a single-subject one on Corto Maltese, the juxtaposition of the permanent collection of the museum and panels from major cartoonists, conferences and debates on comics.

The Centre Pompidou has a long history of acknowledgment and celebration of comics, since its first year of activity in 1977 when it hosted the exhibition “Bande dessinée et la vie quotidienne”. And, generally speaking, France is for sure a country which, more than many others, considers comics an artform equal to literature, painting, cinema and so on. The term French speakers use is a statement itself, since “bande dessinée” (usually shortened as “BD” or “bédé”) simply means “drawn strip”. It’s a neutral word without any diminishing implications like “comics” in English, which inevitably hints at humorous strips and thus a single part of this artistic expression.

Among the various initiatives, the exhibition “Bande dessinée 1964-2024” (Comics 1964-2024) explored different aspects of comics focusing on twelve themes or contexts where this artform thrived and made a difference as a cultural medium.

Comics before 1964

The exhibition starts more or less halfway of comics history. Conventionally the birth of comics dates back to 1896, when the comic strips of Yellow Kid by R.F. Outcault were published in newspapers. From that moment on, up until 1964, comics had already gone through a considerable evolution and development, even though they were mostly considered a form of entertainment. Authors like Winsor McCay (Little Nemo in Slumberland), Lyonel Feininger (Kin-der-Kids) and Will Eisner (The Spirit) explored the potential of comics in terms of narrative, drawings and paneling.

The first superheroes like Superman and Batman were already born and utterly popular. Several authors like Alex Raymond (Flash Gordon, Rip Kirby) or Chester Gould (Dick Tracy) explored different genres like sci-fi or detective stories. Hergé, with his Tintin and his “ligne claire” (clear line) style, created a specific way of drawing comics, which influenced many authors. Osamu Tezuka made the history of manga with his popular creations like Astroboy or Kimba, while other Japanese cartoonists explored more mature and complex stories (called “gekiga”). And Disney comics already conquered generations of readers, with a solid group of authors based both in Italy and in the USA.

Comics 1964-2024 at Centre Pompidou: how to showcase comics?

Even though it covered the period between 1964 and 2024, the comics exhibition at Centre Pompidou didn’t follow a chronological setting. Showcasing the works of 130 artists, it made the visitors explore the medium by thematical areas, such as: “Counter-culture”, “Laughter”, “Fright”, “Dreams”, “As days go by”, “Personal stories”, “Colour, Black and White”, “History and Memory”, “Literature”, “Future Fiction”, “Cities” and “Geometry”.

By showing different approaches to visuals, narrative and themes, the focus is obviously on diversity, on how comics are “just” an instrument capable of telling nearly anything, depending on the author’s sensibility. And yet, putting together America, Europe and Japan, the exhibition also shows similarities and links between authors and works despite the geographical and cultural distance.

The history behind comics’ themes and contents

However, the history of comics can surely be told through the lenses of each room of the exhibition. Just to make a few examples, science fiction marks the transition from adventure stories to space operas. From Flash Gordon to the hermetic and evocative worlds of Moebius and Druillet or mangaka like Osamu Tezuka, Go Nagai and Katsuhiro Otomo, the examples are numerous.

Comedy is where comics mostly started, with comic strips published in newspapers, hence the name “comics” they still bear today. And even if comic strips were often just entertainment, they have evolved through time into one of the most skillful and successful forms of comics, as authors such as Charles Schultz, Quino, and Bill Watterson, as their Peanuts, Mafalda, and Calvin & Hobbes demonstrate.

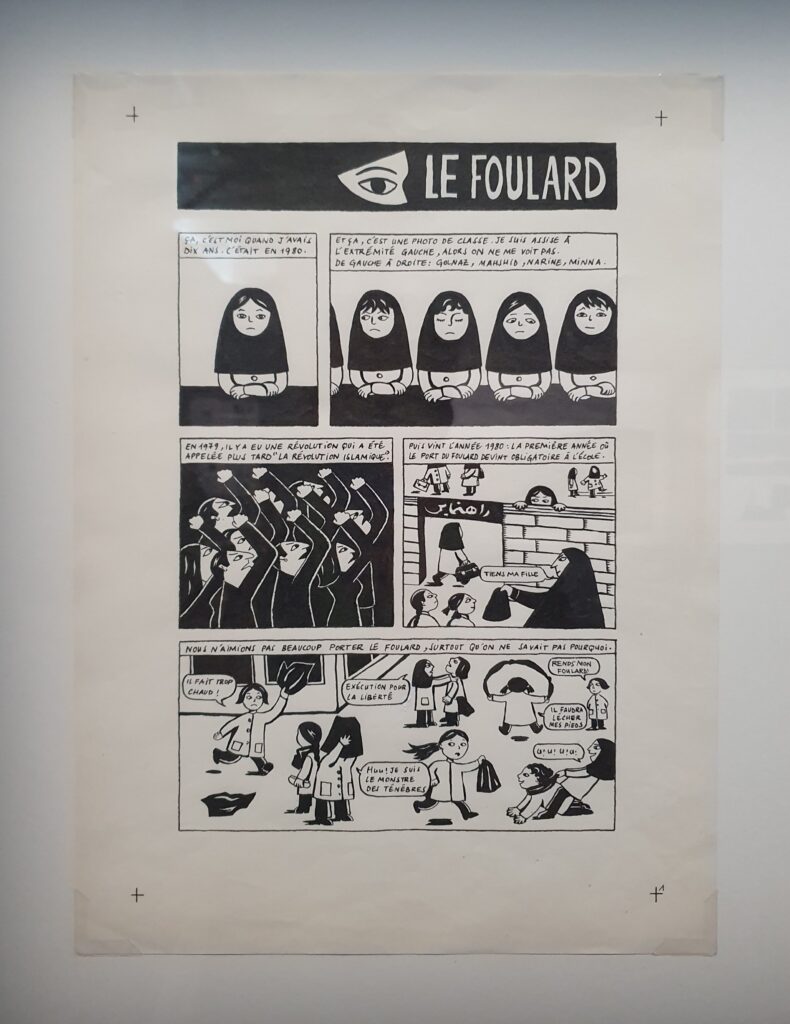

The path of graphic journalism and autobiography keeps on thriving, as shown by Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, capable of blending her private life with Iran’s historical events of the last decades. An even more recent example is the Italian cartoonist Zerocalcare who, although more lightly, has illustrated the war in Syria in Kobane Calling or, recently, the trial against Ilaria Salis in Hungary.

Moreover, the exhibition significantly started with a room dedicated to counter-culture, a major chapter in comic history as it saw a huge renewal and exploration of different paths for this medium.

Comics at Centre Pompidou from counter-culture to culture

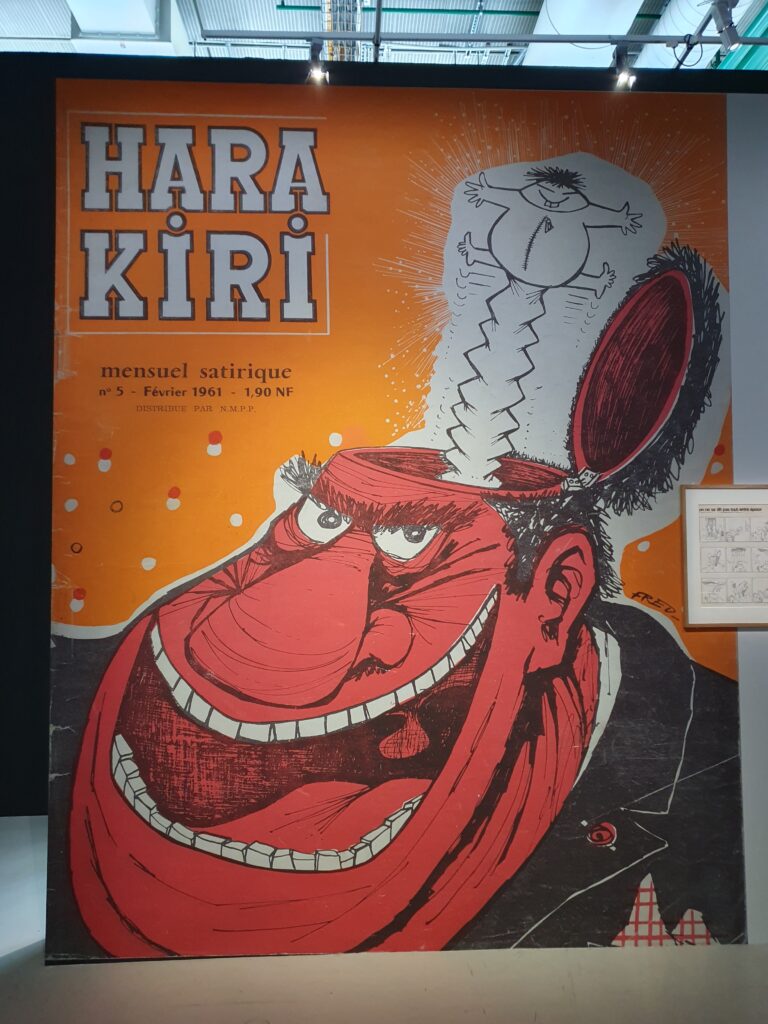

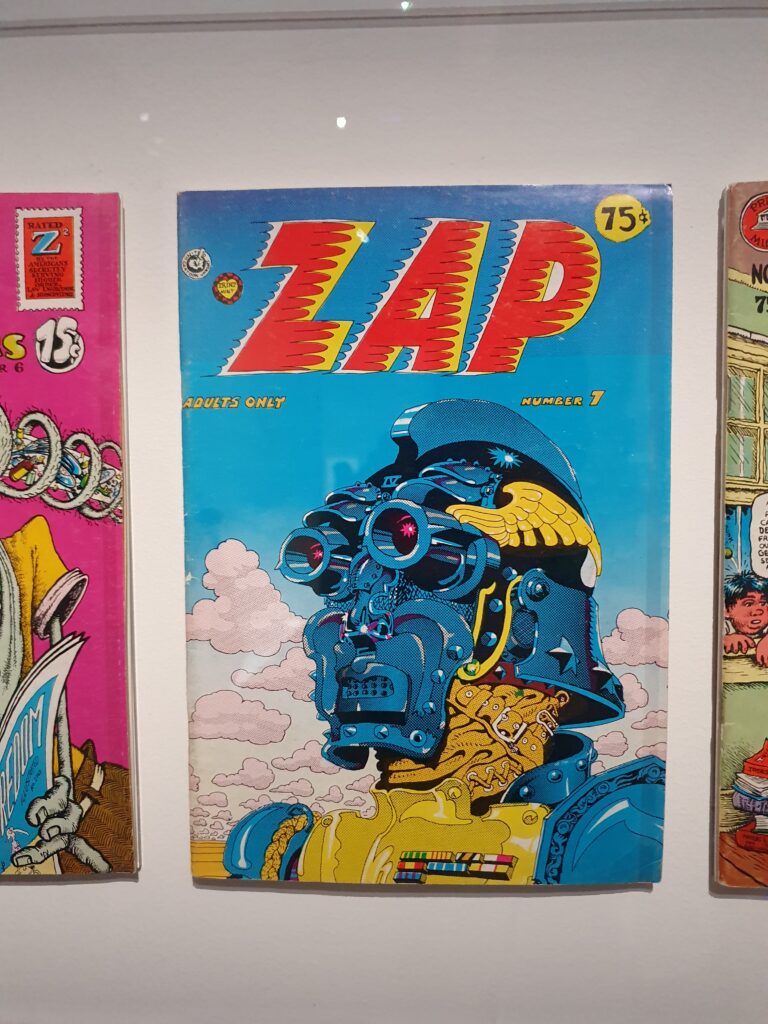

The counterculture of underground comics is perhaps one of the greatest cultural and generational expressions that comics have offered, inscribed in a particularly turbulent yet rich period of innovation such as the late 1960s and early 1970s has been. Magazines like Zap Comix (USA), Garo (Japan) or Hara-Kiri (France), and later on Cannibale and Frigidaire (Italy) redefined the meaning of comics.

No longer just entertainment, but an artistic medium capable of giving voice to a generation, eager to question the contemporary world, always ready to mock common values with a lashing satire and thus also to interpret society in a witty way, and also keen to open up new expressive spaces in the same way that cinema, music or experimental literature were doing.

These magazines were a kind of laboratory where authors took a distance from mainstream works, usually oriented toward kids and young readers, and showed that comics were an art form capable of addressing and accessing readers of any age and taste. Also, during these years comics also managed to gain more acknowledgment as an artistic expression.

What started as a countercultural experiment then became the medium of comics, in the same way as happened for autobiographical stories or for visual styles mingling different techniques and influences. In the long term, these innovations changed the way of actually making comics, from comedy to horror, from the way of using color to the approach to other art forms, branching out into all the other subjects and themes addressed within the exhibition.

Many ways to make comics

Two authors that certainly welcomed the lesson of the countercultural years are Moebius and Philippe Druillet, who found place in the exhibition both in the “Future Fiction” and “Colour, Black and White” areas. Together with Jean-Pierre Dionnet, they created the magazine Métal Hurlant, which further revolutionized comics. Moebius’ innovative way of using vivid colors and neglecting a clear storytelling and, often, an understandable plot, created a new way of presenting sci-fi and comics altogether. Druillet contributed as well to this revolution, as he drew his panels on large scales, filling them with hundreds of details, making them undistinguishable from a proper painting. His dystopic and evocative settings were also enhanced by a highly stylized lettering, which became part of the whole composition.

Experimentalism and essence in comics

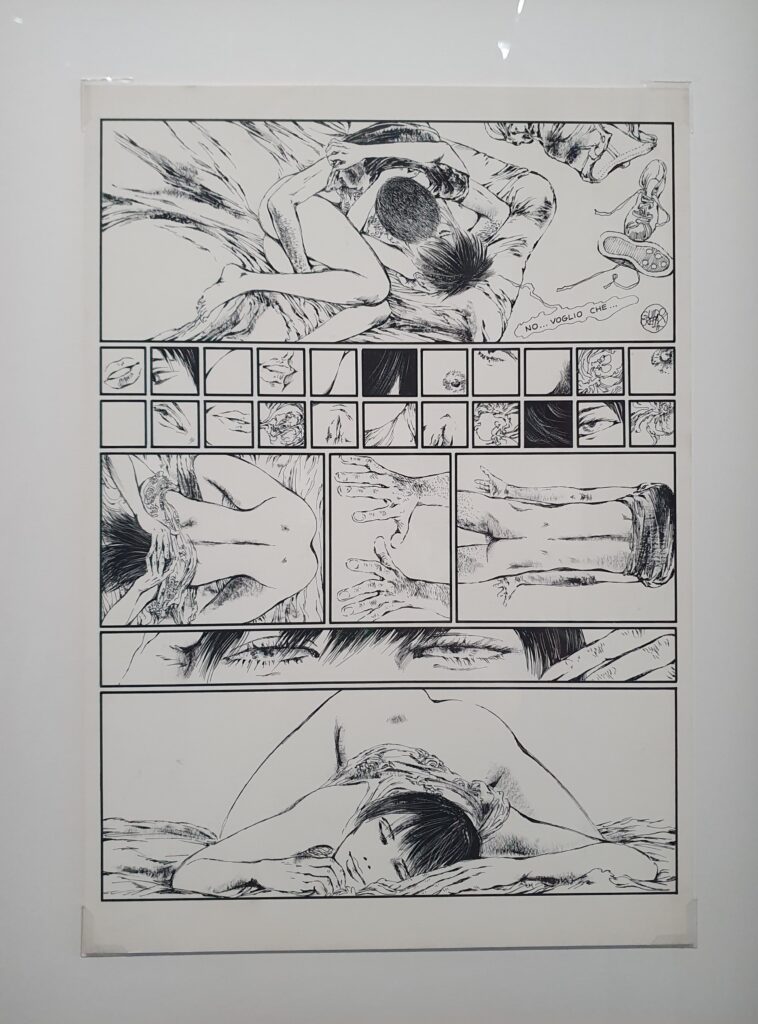

The “Geometry” room, on the other hand, both shows some peaks of comics experimentalism and a reflection of how comics work. The panels from Valentina by Guido Crepax are a statement of how much a panel can be expressive, complex and layered. The combination of full figures, dialogues, action and close-up on details makes the reader experience a variety of sensations that go well beyond the mere reading of texts and images.

While Chris Ware‘s works are an example of how much the author can bend the space of the panel to create original effects, intertwining visual and narrative features. The reader shall “explore” more than actually read his comics (Building Stories is not even an actual single book, but a collection of elements one can read in different ways).

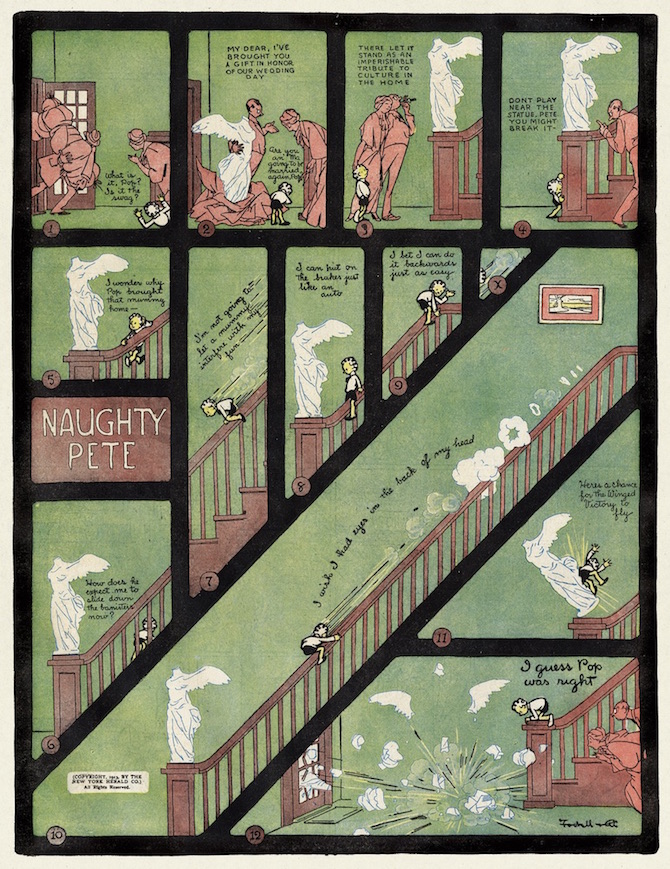

But as comics are a “sequential art” as Will Eisner once said, geometry is embedded in their essence. The way the author handles time and space on the panel can completely change the story they’re going to tell. A lesson well understood already by early authors like McCay or Charles Forbell, who deeply connected the panelling to the story they were telling.

Something’s missing? From shonen manga…

Undoubtedly the Comics 1964-2024 exhibition at Centre Pompidou was thorough in exploring many aspects of the medium. Nevertheless, maybe at least an extra room could have been added, regarding action comics or, in general, the more recent mainstream front. Both the Japanese side, with battle and sports manga, and American superhero comics have conditioned a large part of the comics market in recent decades. Moreover, many successful authors in this field created comic icons which made history in the medium.

Talking about comics nowadays it’s hard to overlook, for example, Akira Toriyama, who with Dr. Slump and Dragon Ball has dictated the rules of mainstream comics for the past 40 years, with the dynamism of his panels, his memorable characters and his always appealing designs.

A path followed by many other authors, from Eiichiro Oda (One Piece) or Masashi Kishimoto (Naruto) to authors who have offered more structured and layered content such as Hiromu Arakawa (Fullmetal Alchemist) or Hajime Isayama (Attack on Titan). Or, even, more recent successes undoubtedly linked to Dragon Ball, such as One-Punch Man by One and Yusuke Murata or My Hero Academia by Kohei Horikoshi. Equally influential comics were, just to give a few examples, Ashita no Joe by Asaki Takamori and Tetsuya Chiba, which talks about boxing or, later on, Takehiko Inoue‘s Slam Dunk, that marked a generation of readers by spreading basketball and sports stories.

…to superhero comics

The same goes for superheroes, starting from Jack Kirby’s and Stan Lee’s creations (like Thor or the Fantastic Four, shown in the exhibition). Along with them, other authors’ interpretations of superheroes like John Romita Sr.’s Spider-Man, John Byrne’s X-Men or Neal Adams’ Batman are the source of superheroes as we know them today.

It’s thanks to their works that great innovators, such as Frank Miller, Todd McFarlane, John Romita Jr. or Jim Lee, became who they are and reinvented and expanded the visual potential of action comics as well. An evolution made possible also by scriptwriters like Alan Moore (Watchmen, V for Vendetta) and Neil Gaiman (The Sandman), who contributed to dignifying mainstream comics by making their stories more complex and layered.

A huge celebration of comics

However, as comics are a multifaceted medium, it would be impossible to include every aspect of them in a single exhibition. “Comics 1964/2024” for certain managed to take the visitors through a thematical journey where they could experience and feel the different forms of comics.

Moreover, “BD à tous les étages” had the merit of openly putting comics on the same level as any other art. It doesn’t happen often to see comics panels next to renowned painters. For example, the other exhibition, “Le bande dessinée au Musée”, placed cartoonists like Winsor McCay, Will Eisner, Hergé or Lorenzo Mattotti in the heart of Centre Pompidou, next to authors like Picasso, Matisse, Klee or Bacon. Thus, it highlighted both the influences comics welcomed from painting and the fact that a panel is as much worthy of consideration as a picture. An acknowledgment for comics that is getting wider and wider and that, hopefully, will keep on spreading thanks to cultural initiatives such as this.