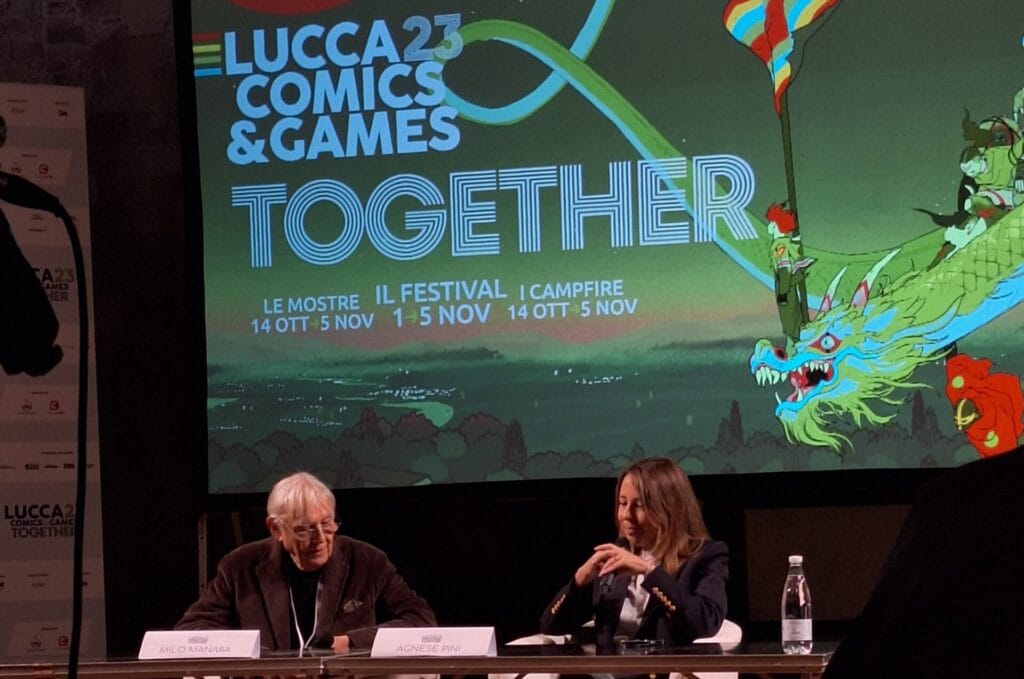

Milo Manara aged 78, after a fifty-three-year-long career, and forty years after the publication of his first comic book Il Gioco, has a wish. He no longer wishes to be classified only as an erotic illustrator. In the interview with Milo Manara conducted by journalist Agnese Pini during the recent and renown international comics fair Lucca Comics & Games 2023, the artist takes us through his perspective on eroticism among revolutions, censorship, art, and current events.

I have never done anything not to deserve this nomination, but I am not only this. I have also accomplished many other things. Art should have no labels, but in the end labels are sewn on us even against our will.

Milo Manara

Eroticism from the 70s to nowadays

In January 1969, Manara’s first comics were published, produced in the previous year. This was a period of revolutions and great social changes. From fashion, with the arrival of the miniskirt by British designer Mary Quant, to music with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones changing the perception of the social meaning of this art. “Similarly, in those years eroticism had a sense of rebellion and social liberation, a sense of freedom that it no longer has today,” Manara says.

Manara takes as an example Pop singer Elodie, who faced the taboo of artistic nude for the cover of her new album. The artist had already broken down this taboo with his comics forty years ago. In fact Manara himself portrayed the singer’s nude on the cover of Red Light.

Eroticism as Manara represented it then, in a joyful, free and – as he calls it- maybe even unaccountable way, today has become a much more delicate and complex subject to deal with, because of a number of sensitivities that have to be respected and that – as the artist says – are sanctity.

In art, the nude has always been celebrated: just think of Praxiteles, a master of the nude who lived more than 2,500 years ago, or Bernini, an artist often associated with eroticism because of the expressions of the ecstasies of the saints he portrayed.

Was art freer 2,500 years ago?

According to the artist, yes, but this did not only have negative aspects. Manara refers to what might have been the caricatures of the old Italian comedy, for example towards homosexuals. “Today no one would dare to do such a thing,” he says, “so we can consider this a positive evolution.”

The problem comes when the enclosure is excessive and the censorship of political correctness kicks in. Manara in fact argues that art should be free; no one should be able to choose for others what they can see or read. “Works of fantasy, of thought, which therefore do not physically involve people, should not be censored in any way.”

Manara’s cover censored by Marvel

The artist talks about being a victim of censorship twice. The first, as well as the most relevant, occurred in Africa, at the time of apartheid. Manara was on the receiving of censorship for three of his books. Much to his surprise, however, these were not erotic, but political.

The second and more recent censure, however, the illustrator received from Marvel. Manara had been asked to draw Variant Covers of some of the Superheroines of the Marvel Universe. “Although I am not a great connoisseur of this world, I have always found the modern Olympus composed of these heroes fascinating,” Manara says, “I find it an interesting way to update mythology. That is why I willingly accepted Marvel’s proposal to draw these Variant Covers.” Unexpectedly, however, what caused so much scandal was his Spider-Woman because of the pose in which the artist had portrayed her, even though that was the traditional Spider-Man pose.

Nude and scandal, Manara’s own thoughts

The artist responds to this question by quoting Umberto Eco‘s novel, The Name of the Rose, a work for which Manara himself proposed his own comic book interpretation.

Beautiful as the Moon, shining as the Sun and terrible as an army deployed in battle.

Adso from Melk, The name of the Rose, quote from the Song of Songs

These are the words of Adso of Melk, a character in the novel The Name of the Rose, when he stands before the naked body of a woman.

“Perhaps this is precisely what the woman’s body still is today,” Manara says, “an army deployed to battle, for the disturbance caused at the sight of nude is terrible.”

According to Manara there is a clear difference between sex and eroticism. In fact, the artist finds eroticism to be an evolution and cultural elaboration of the sexual act, while he sees pornography instead as a mere display of sex. Eroticism therefore goes beyond mere nudity or the sexual act; indeed, it can safely exclude the latter. In fact, in this regard Manara points out that in his 53-year career he has never, or almost never, depicted a sexual act.

Botticelli’s Venus between eroticism and sacrality

Manara believes that Venus has a powerful erotic charge, but hers is a very elaborate eroticism. The woman’s body evokes emotions in an ancestral way. The artist explains how the woman’s body, unlike the man’s, is charged with many symbols, such as motherhood. “Despite being helpless, the female nude is much more powerful,” Manara continues, “also due to its sacrality.”

Today this sacrality is often violated, using the female body for commercial purposes. the artist poses as an example that of television advertisements, where the sensuality of the woman is used to promote the purchase of an object.

“This sacrality should be adored and respected, and those who violate it have not understood anything about life, I think.”

The celebration of the female body in art

The woman’s body has always been celebrated throughout art history, just think of Rubens, who portrayed the female body quite differently than Botticelli. In fact, Rubensian women had less toned bodies with many flaws.

Among the art masters mentioned by Manara then are Klimt and Rodin. Both artists let models express eroticism in their studies. Both Klimt’s and Rodin’s drawings in fact include several erotic sketches, Manara says. “Even Caravaggio,” Manara says, “who never portrayed female nudes, reproduced many male nudes with a high erotic charge.

The terribleness of Iranian women

During the meeting, Nation’s editor Agnese Pini draws attention to the issue of Iranian women who have been killed for not wearing the Islamic chador properly. Showing their hair, often considered the highest symbol of a woman’s sensuality.

According to Manara, what is happening to women in Iran today is a symptom that their terribleness and their power are still not accepted, particularly by Iranian male society. This terribleness still frightens Iranian men.

Manara on Israeli sponsorship

“An artist, when the world is overwhelmed by disasters, must behave as he feels he should,” is how Manara responds to journalist Pini on the issue of Israeli sponsorship of the LC&G.

As a matter of fact, Manara does not judge the choices of other artists such as Zerocalcare and Fumetti Brutti who chose not to participate in the event because it was sponsored by Israel.

“I felt I chose it because I don’t feel a moral enough to judge Israel or others. I consider what is happening in Israel today to be the direct consequence of what happened here before 1948.” affirms the artist referring to the Shoah and the persecution suffered by Jews, prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948.

“This state was dropped into an area where there was already a population, this caused complications that led to the current ongoing war. But I as a person who is guilty, as an Italian, I don’t feel I have the moral caliber and right to be able to judge, precisely because this is the direct consequence of how the Europeans behaved toward this people. Zerocalcare felt it was more right not to participate, and he did very well, everyone has the right to do what they feel like doing, I felt like coming instead.”

Beauty as an antidote to violence

In a world full of horrors, Manara helps the audience discover once again beauty: “Beauty is there where it has always been, it is up to us to choose whether to suppress it or set it free. There are so many taboos, such as that of war. Beauty is the exact opposite of this unsuppressed instinct to kill,” he explains, “It is absurd to think about the evolution of our culture, which rejects this kind of violence, but at the same time it is always pervasive.

“Just think of the baby-gang phenomenon, formed by a young generation that has the future of the world in its hands,” he concludes, “Beauty is the opposite of violence, beauty is always there, only it is increasingly obscured.”