Prodigal Summer by Barbara Kingsolver Review | Celebrating life and desire

Author

Year

Format

By

Author of several books of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry, Barbara Kingsolver is today one of the most renowned U.S. writers. She is the recipient of literary prizes such as the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for the novel Demon Copperhead (2022), and the Women’s Prize for Fiction for Demon Copperhead and The Laguna (2010). Since 2004, she has lived in southern Appalachia in southwest Virginia, where her fifth novel, Prodigal Summer (2000), is set.

Ecology and the relationship between humans and nature are recurrent themes in her works, which she explores by weaving scientific rigor into stories of love, death, and more-than-human entanglements. Her accuracy results from years of biology, ecology, and evolutionary biology studies.

Prodigal Summer is an example of this trend in her writings: it is a celebration of love and regeneration, set during one humid and fecund summer in the fictional Zebulon County in Appalachia. Instead of weighing the plot down, the references to principles of ecology and biological behavior enrich it with meanings and connections, both among characters and between characters and readers.

Intersecting stories

The plot is made up of three different storylines, recounted in alternating chapters. In its structure, Prodigal Summer resembles other popular works of fiction, such as Kathryn Stockett’s The Help, in which the three main characters relate their stories in different chapters, or Richard Powers’ The Overstory, made up of different, but intersecting, narrative strands.

The chapters titled “Predators” tell about 48-year-old forest ranger Deanna Wolfe, who has been living alone in a cabin for two years. She is strong, independent, and careless: a sort of eco-feminist hermit. With the beginning of the lush summer in the forest, two events unsettle her routines and engender obsessions: coyote traces and the meeting with Eddie Bondo, a hunter.

“Moth Love”, by contrast, focuses on Lusa Maluf Landowski, a “bugologist” who has rejected a promising city life in entomological research to marry a farmer, Cole Widener. After a year of marriage, her life undergoes a radical transformation as a consequence of Cole’s death during work. Her story develops as a coming to terms with loss and mourning, as well as a radical reinvention of the self.

Finally, “Old Chestnuts” shifts the attention to two elderly, feuding neighbors, Garnett Walker and Nannie Rawley. They epitomize the many forms care can take: even if both value nature and believe in the importance of preserving certain species, Garnett does so by applying pesticides and chemical fertilizers, while Nannie practices organic, regenerative agriculture.

Lust, life, and death

Kingsolver manages to weave these different stories into a sensual narrative that celebrates life-death cycles and natural balance. Each being in the forest and in the valley seems caught in an urge to procreate, generate life, and store it for the winter months to come.

This celebration of life and desire comes in many forms: it is in the eroticism of Deanna and Eddie’s encounters, in Lusa’s slow transformation into an independent farmer, and in Garnett’s realization of his need for affection. Above all, life and desire pervade the natural world in which humans are but one of the many species:

The dawn chorus was a whistling roar by now, the sound of a thousand males calling out love to a thousand silent females ready to choose and make the world new. […] Nannie had asked her once in a letter how she could live up here alone with all the quiet, and that was Deanna’s answer: when human conversation stopped, the world was anything but quiet.

Pages 52-53.

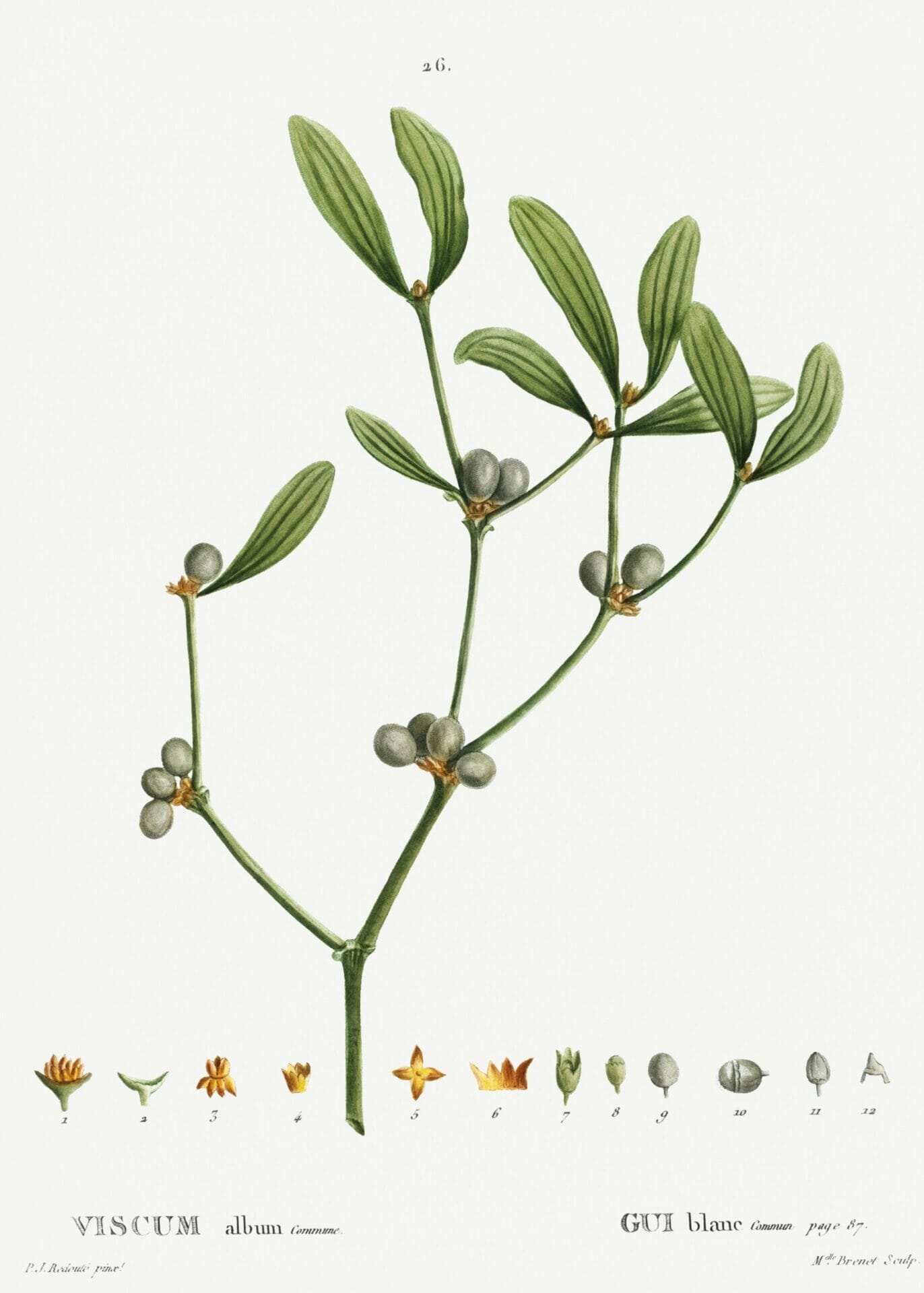

Through a well-crafted, voluptuous portrayal of human – more-than-human enmeshment, Kingsolver enchants these stories with wonder and beauty, without romanticizing the hardships a farming community faces. In its eulogy to coyotes, moths, and chestnuts, Prodigal Summer reminds of Macfarlane and Morris’ The Lost Words, a collection of poems devoted to instilling life into nature-related words that have disappeared from junior dictionaries. Kingsolver manages to infuse into her prose the enchantment that Macfarlane and Morris try to retrieve through poetry.

Poetic lessons in ecology

Kingsolver’s knowledge of ecology and animal behavior surfaces multiple times in the novel through her characters: Deanna has written a thesis on coyote ethology, Lusa can easily recognize different moth species, Garnett is a goat expert, and Nannie tends the only organic orchard in the region. The precision with which the author describes each of these fields of knowledge is striking.

Deanna’s relationship with coyotes is particularly emblematic. Multiple times she argues for the necessity of protecting keystone predators such as coyotes from hunters, as their presence in natural environments is essential to ensure balance among species.

Scientific precision is not uncommon in environmental fiction. For instance, Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future is full of scientific descriptions, technical details, and real data, which the author uses to depict a near-future scenario.

As Prodigal Summer takes place in the present, it shares similarities with Richard Powers’ environmental novels The Overstory and Bewilderment. Because Kingsolver and Powers are both U.S. popular authors with a background in science, the magazine Poets&Writers brought them together in 2018 to freely discuss their creative processes and the meaning of being an author of environmental fiction. The following year, 92NY invited them to share some passages from their books and discuss them together.

Notwithstanding its scientific rigor, Prodigal Summer remains a story of disarming simplicity and clarity, hinging on universal emotions and celebrating life in all its forms. Readers are thus invited to share Deanna’s simple prayer:

Thanks for this day, for all birds safe in their nests, for whatever this is, for life.

Page 267.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic