Batman: The Killing Joke | Who's the madman?

Year

Format

By

There where these two guys in a lunatic asylum…

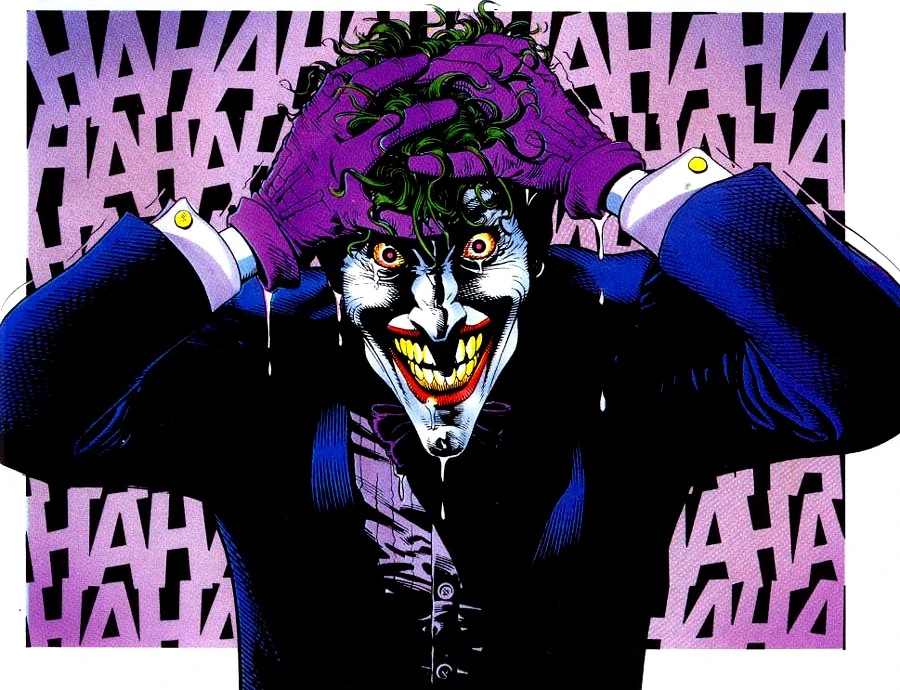

This is how Batman: The Killing Joke begins. A joke in which the two lunatics are none other than Batman and the Joker themselves. In Batman: The Killing Joke, released for DC comics in 1988, written by Alan Moore (already working with DC comics on Watchmen), and illustrated by Brian Bolland‘s with John Higgins‘s coloring, the reader enters in the endless circle that is the relationship between Batman and the Joker. All while the Joker tries to point out that all humanity is just one bad day away from madness.

A superhero story thus becomes a way to explore moral dilemmas and dehumanizing crimes. Over the years, it has undergone different interpretations, which has also raised controversies regarding the treatment received by the only female character present in it. Nevertheless, it is one of the most influential comics of all time. It also won the Eisner Award for Best Graphic Album in 1989.

The Killing Joke: the thesis of the Joker on madness

In The Killing Joke, according to the Joker, madness is the only emergency exit to what is the meaningless of life. There cannot be an improvement, a resolution, a better future. To accept it, one has to reject what tries to make sense of what has no meaning: society, and its false sense of security. Ironically, he states that what it takes to get mad is just one bad day.

And that is why, to others, the Joker is crazy: because he is the one who does not accept human rules. He just sees what everybody is too blind to catch. This is the same concept in Christopher Nolan‘s The Dark Knight (2008), where the Joker played by Heath Ledger wants to prove that moral values are valid as far as they are convenient.

I think the underlying belief that Alan Moore got across very clearly is that on some level the Joker wants to pull everybody down to his level.

Christopher Nolan in a 2008 Q&A

Another woman in the refrigerator

I asked DC if they had any problem with me crippling Barbara Gordon, and, if I remember, I spoke to Len Wein, who was our editor on the project. [He] said, ‘Yeah, okay, cripple the bitch’. It was probably one of the areas where they should’ve reined me in, but they didn’t.

Alan Moore for the magazine Wizard

To prove his thesis, in The Killing Joke the Joker wants to drive detective James Gordon to madness. So, like in a comics version of Stanley Kubrick‘s A Clockwork Orange, he breaks into Gordon’s house and shoots his daughter, Barbara aka Batgirl. The wound paralyzes her from the waist down and she also gets sexually abused.

But the violence suffered by Barbara is only functional to the story, and no one cares about her “bad day”. Thus, the writer Gail Simone included the character in her list of Women in the refrigerator. It refers to women in comics who suffer violence whose effects, unlike their male counterparts, continue to endure in the long run. Barbara continued to be paraplegic for years even if The Killing Joke was officially non-canon.

Whether it is right or wrong to question how a story should have been written from a 30 years distance, it is important to point out how female characters were used in the past, in order to make them more complex and integrated in the future.

As a matter of fact, she has been developed further: she then became Oracle, fighting crime behind a computer as an intel specialist. Gail Simone herself made her a founding member of the Birds of Prey. Eventually, she will heal and turn back on being Batgirl.

The symbolism of Brian Bolland and John Higgins

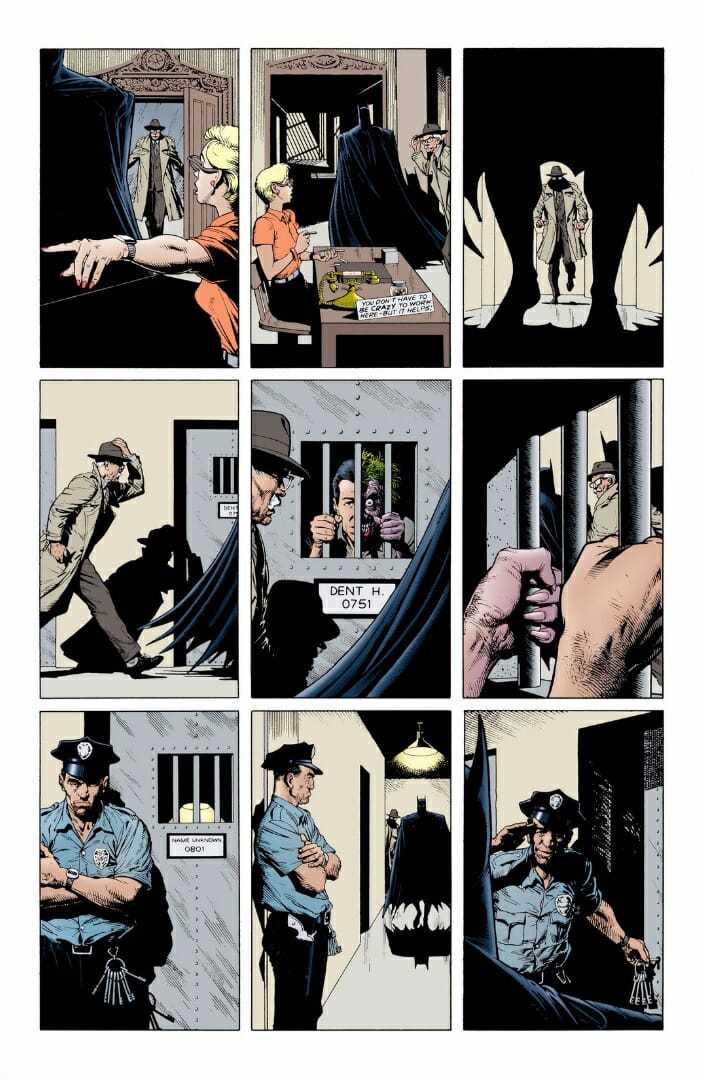

Bolland’s drawings are full of symbolism. When Batman arrives in the asylum to speak with the Joker, he passes in front of the cell of Two-Face. His aspect is like a preview of the duality present in The Killing Joke: madness and sanity, right and wrong, Batman and the Joker.

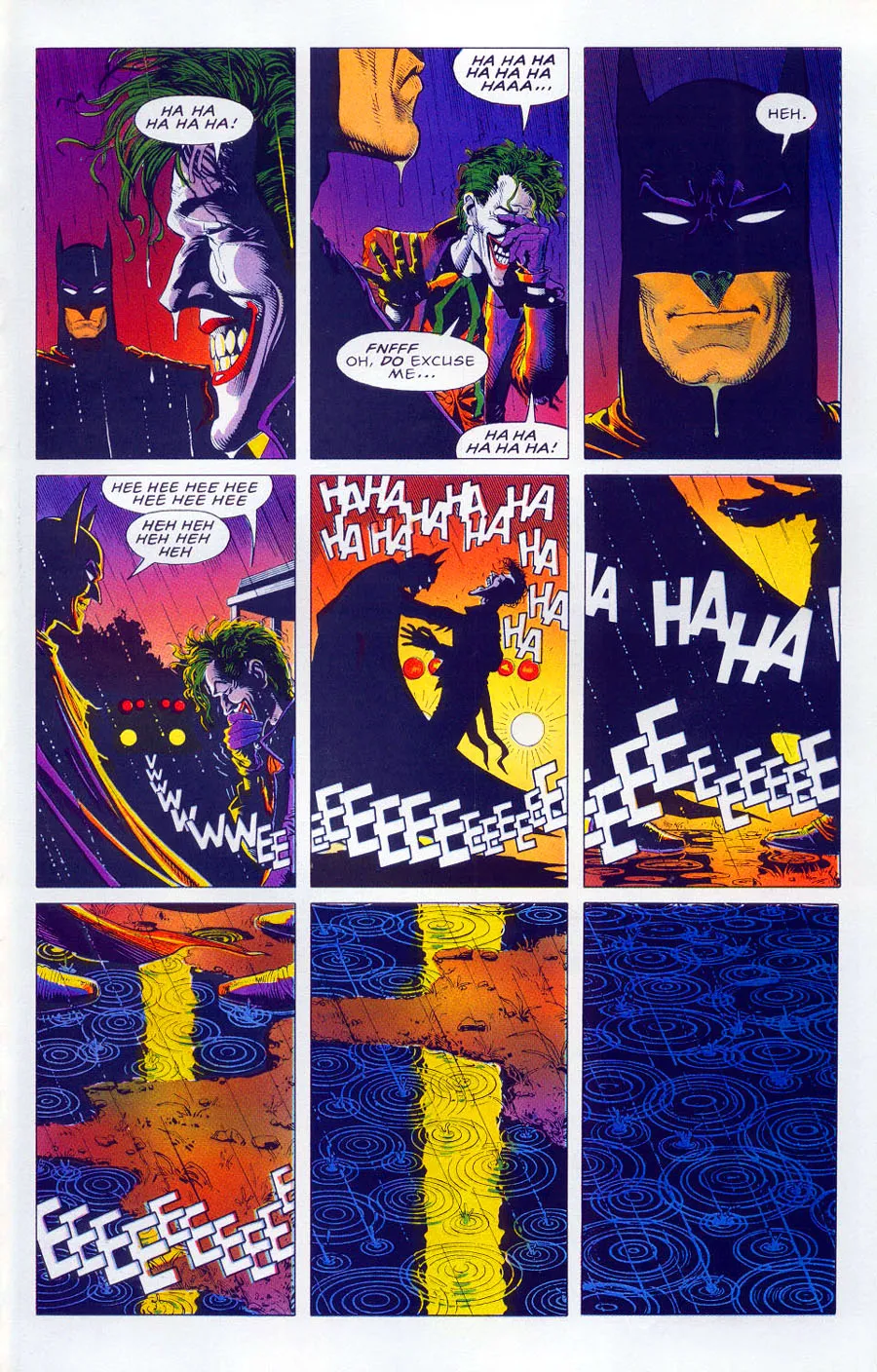

The final cartoon is the utmost expression of Bolland’s stylistic choice. It is exactly the same as the first on the first page of the story, to indicate that Batman and the Joker will live a story that never ends because each of them needs the other to have a purpose.

The colors themselves are crazy. Higgins brought out, even more, the core of The Killing Joke being a journey into the twisted mind’s madness of the Joker. Orange and purple colors and their shades are predominant. Lit, disturbing, not at all representing the true reality of things.

Later on, Bolland made a coloring of his own, which presents much more noir and dark atmospheres and is devoid of the feeling of madness expressed by Higgins. Adding a further dichotomy, it’s as if the reader could read the same story but from Batman’s perspective, while Higgins bought the Joker’s one.

An ending full of questions

One interpretation of the story could be that Batman doesn’t reject the Joker’s concept of the world, but he tries to force a meaningless life into rationality anyway. They, therefore, are two sides of the same coin. They are both crazy. But The Killing Joke shows that Batman and the Joker have different methods of dealing with their madness. Eventually, they come to terms with their similarities and have a big laugh.

However, the comics leaves room to further interpretations: Grant Morrison, for example, renowned author for the Batman series, believes Batman eventually murders the Joker, despite his strict no-killing golden rule. After all, the joke is literally or only metaphorically killing? As they are trapped in an eternal cycle, Batman’s extreme decision could be proof of his lost faith in redemption.

Personal regrets don’t affect history

In recent years, Alan Moore has diverged strongly from many of his own creations. In The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore, written by Moore himself and Geroge Khoury, he said that The Killing Joke was just something about two DC characters and nothing more.

However, as writer Julian Darius explains in his And the Universe so Big: Understanding Batman: The Killing Joke, the authorial intent is a critical fallacy because if one day someone will find a note from Shakespeare in which he explains that he wrote Hamlet only for money and he thinks it is a horrible play, the work would still remain one of the greatest masterpieces in history.

The same goes for comics and The Killing Joke: a must-have on the shelves of the history of comics. A story in which the ultimate joke is that the line between madness and sanity is more blurred than we think. Not just in comics, but in the real world itself.

Tag