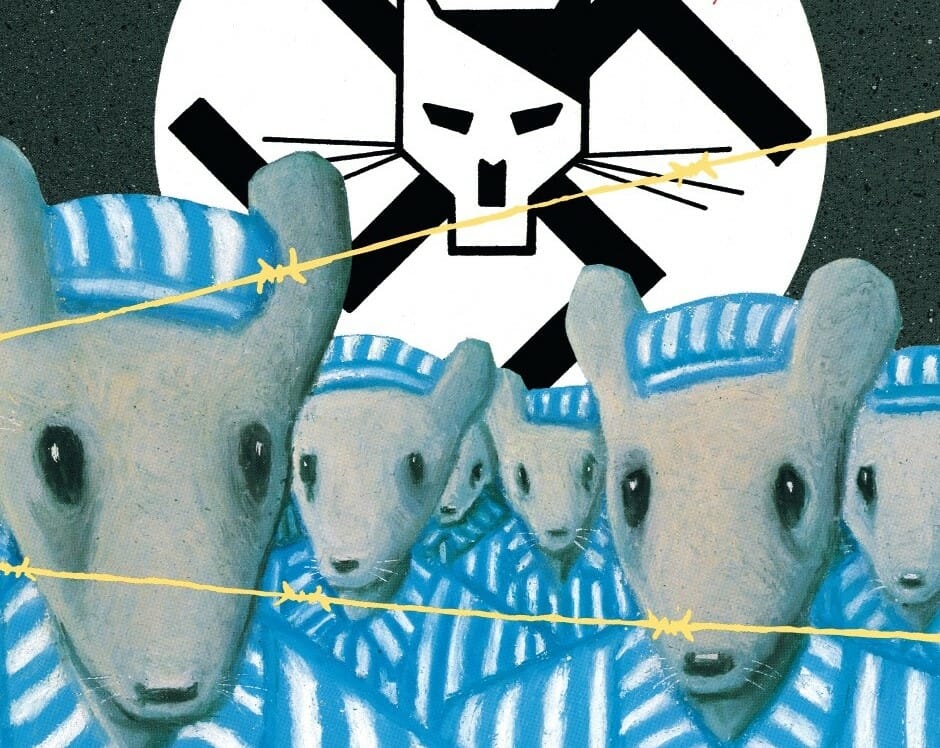

Curzio Malaparte’s 'The Skin' | Humanity at its worst

Length

What is more of a shame, losing a war or winning it? Italian writer Curzio Malaparte lived through the unique occurrence of experiencing both conditions simultaneously. A longtime anti-fascist, he served in the Italian army during World War II, despite his stoic opposition to its leader. But upon learning of the Armistice of Cassibile, marking Italy’s surrender to the British and Americans, he joined the ranks of his former enemies to liberate the country from Nazi occupiers. A few years after the war ended, he recounted his frontline experiences in his renowned novel The Skin (1949), bearing witness to humanity’s loss on both sides of the conflict.

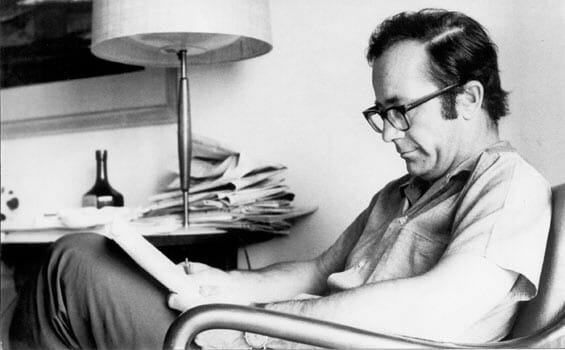

The novel as a reportage

A classic of 20th-century Italian literature, The Skin offers one of the most original perspectives on the war’s final days. It takes its name from what Malaparte considers the flag of all Europeans during World War II: their skin, which they desperately seek to save.

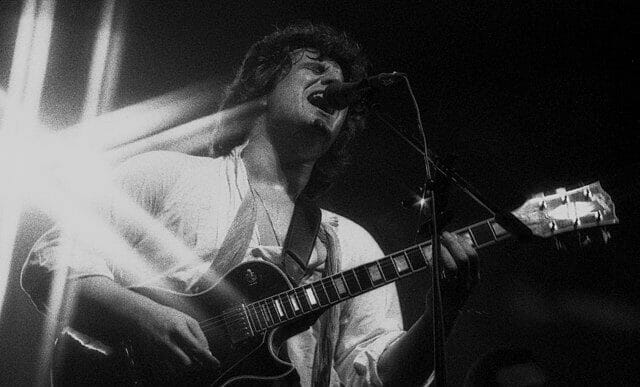

Malaparte’s narrative unfolds as a piece of journalistic reportage, delivering a blunt account of those tumultuous days. By the time it was released, Malaparte was already renowned for his vivid war reporting. A few years earlier, in 1944, he had risen to international fame with Kaputt, a personal account of his experience on the Eastern front in World War I.

But while his style and point of view are recognizable across the two works, there was something new to The Skin. And in part, this had to do with its setting — the devastated city of Naples.

A modern tragedy

As World War II drew to a close, Naples lay in ruins, heavily bombed and with a death toll of nearly 25,000, mostly civilians. But despite the city’s pervasive despair, artists recognized a lingering sense of magic amidst the rubble. Hungarian author Sándor Márai, who would move there as an exile after the war, in The Blood of Saint Januarius wrote that for the Neapolitans “miracles are part of the family”.

Malaparte recognized this unique factor and felt that raw realism alone couldn’t capture the blend of horror and wonder he witnessed. Hence, for The Skin, he drew inspiration from the works of the Greek masters, mainly Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides.

I have become convinced that it is easy to write beautiful things when you have behind you a bit of that mythical world, that poetic world in which the audience, if not the author themselves, believed.

Curzio Malaparte – Diaries

Thanks to these powerful references, even the most miserable characters stand on the page as tragically as Greek heroes. But unlike their classical counterparts, they are stripped of all honor — a condition as painful as the worst of diseases.

The plague of being a loser

Malaparte sets the stage by announcing that his novel takes place during the days when the “plague” took hold. In the autumn of 1943, a mild form of petechial typhus was rampant in Naples. But despite the relatively low mortality rates, the author suggests a deeper affliction:

That was a plague profoundly different, but no less horrible, than the epidemics that occasionally devastated Europe in the Middle Ages. The extraordinary character of this newest disease was this: it didn’t corrupt the body, but the soul. The limbs remained, in appearance, intact, but inside the flesh envelope, the soul deteriorated, dissolved.

Curzio Malaparte – The Skin

A combination of German atrocities against the civilian population, destruction of infrastructure caused by bombing, lack of food and disease led to a climate of desperation in the city as it was liberated by the Allies. Mothers resorted to selling their children to soldiers, and women were reduced to commodities in market stalls. What made this tragedy worse was the soldiers’ exploitation of such misery, a situation that deeply resonates with Malaparte’s classical references.

The burden of the winners

Being a good winner is a topos as old as literature itself. In an exergue to The Skin, Malaparte reports a quote from Aeschylus’ Agamemnon: “If they respect the temples of the vanquished, the victors will be spared”. Accordingly, the author maintains a conflicted position toward American soldiers throughout the novel.

His gratefulness to the liberators of Italy is evident in every page. But despite this, and despite the profound friendships he shares with some of the servicemen, Malaparte can’t help noticing a certain cruelty of the US army towards the people of Italy. A cruelty that is only possible when the counterpart is no longer considered human.

A book for modern times

Winning a war, it turns out, is just as dehumanizing as losing it—both outcomes intertwined. Italy’s culpability in allowing fascism to take root didn’t excuse the cruelty or humiliation inflicted upon its people. Being guilty of shameful deeds doesn’t justify such retaliations.

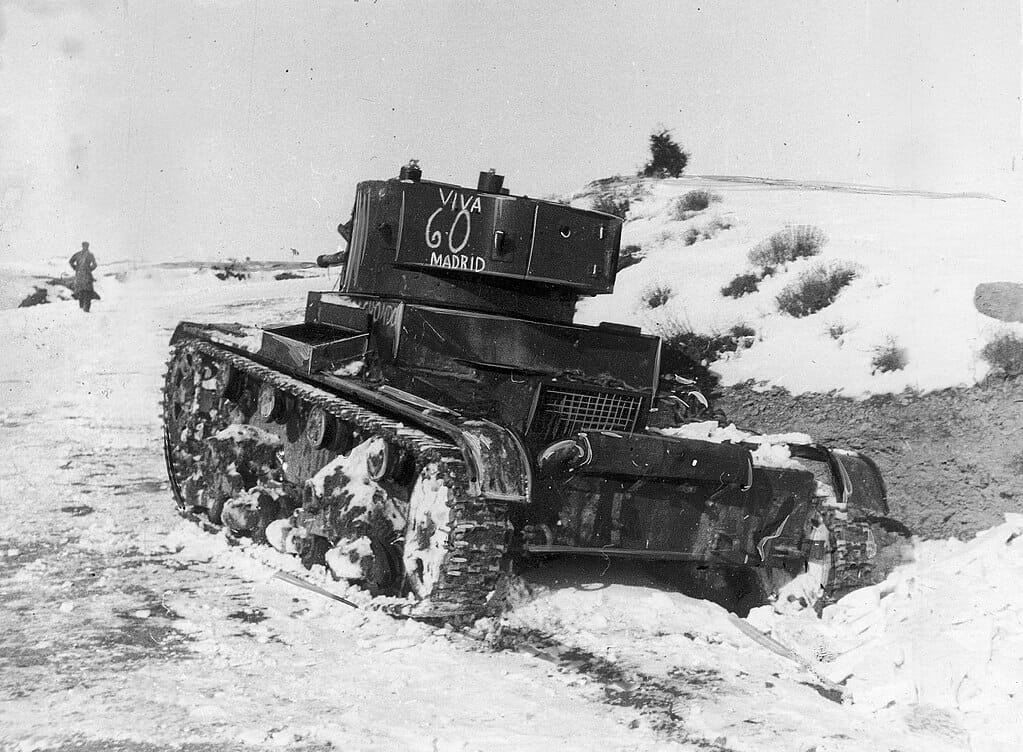

Several decades later, The Skin remains a poignant reflection on the complexities of war, alongside works like George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia and John Hersey’s Hiroshima. But Malaparte’s fierce style and thought-provoking perspective render his work unique. In Encounter, Milan Kundera even lauded the novel as one of the greatest of the 20th century, noting:

With his words he hurts himself and others; the speaker is a man in pain. Not a committed writer. A poet.

Thanks to its profound humanity, The Skin stands as relevant today as it was upon its release — if not more so. A complicated book for complicated times, it is the perfect read for those who wish to step in the shoes of the victors and those of the vanquished. With its poignant account of the last days of the war, it makes a point that may apply to any conflict: most of the time victims aren’t innocent, and heroes are always tainted.

Tag