Operación Masacre by Rodolfo Walsh | When literature needs to be dangerous

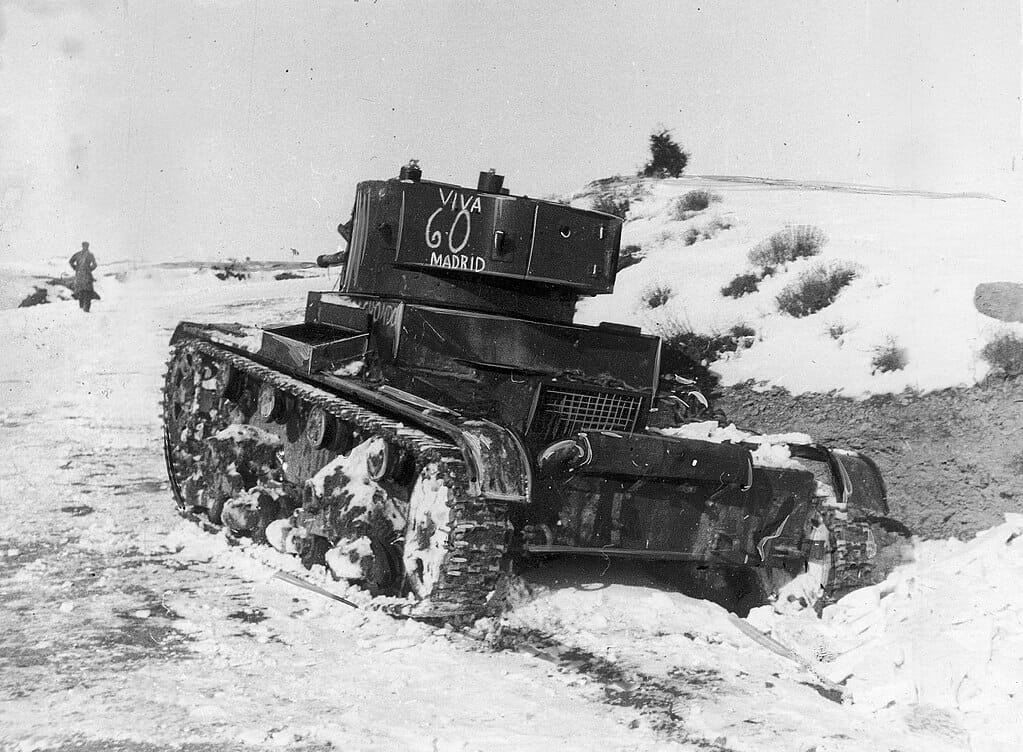

On June 9, 1956, twelve innocent men gathered in a house in Vicente López, a suburb of Greater Buenos Aires, to listen to the final of the South American middleweight boxing championship. Most of them had no idea that another fight was going on in Buenos Aires as they listened to the match.

In the military base of Campo de Mayo, thirty kilometres from the house, the colonels Cortínez and Ibazeta were attempting a revolution against the bloody regime of General Aramburu.

Before the boxing match was over, the Provincial Police unlawfully broke into the house and captured the twelve men, assuming they were involved, but without making accusations. Then, a few hours later, they brought them to a desert field to execute them. The massacre would have passed under silence were it not for the strenuous investigation of a young journalist and writer, Rodolfo Walsh.

In November ’56, Walsh started investigating the shooting. A search which eventually led him to find seven hidden survivors and to demonstrate the blatant unlawfulness and invalidity of the Police’s actions. But finding a publishing house was almost as hard as reconstructing those facts. After a long, unsuccessful search, he managed to make his findings public in the form of nine articles ina weekly newspaper. He gave them the title Un libro que no encuentra editor (A book that can’t find a publisher). Then, in December 1957, he finally found one. Operación Masacre came out as a book, and it was bound to make history.

The art of reality

Published in 1957, Operación Masacre is considered the first major non-fiction novel of investigative journalism. It came out nine years before Truman Capote’s classic In Cold Blood, which is often credited as the first work of this kind. In a time when the novel was still regarded as a superior literary genre, Walsh sensed the artistic potential of chronicle, testimony, and journalism. The 6 June shootings made it evident: reality was too brutal and unjust to let literature ignore it. And Walsh clearly knew how to shape it into art. As he himself explained years later:

In the future, perhaps, the terms will even be reversed: what will really be appreciated in terms of art will be the elaboration of the testimony or the document, which, as everyone knows, admits any degree of perfection. Obviously, in the montage, the layout, the selection, the research work, immense artistic possibilities open up.

Accordingly, in Operación Masacre, much of the artwork is entrusted to composition and montage. Walsh borrows the narrative strategies of the detective novel and applies them to the raw material reality hands him over. Without being blatant, he presents evidence throughout the book. The narration is artfully fragmented to build suspense. Every scene is a piece in a dramatic and investigative mosaic that becomes whole in the conclusion.

Walsh’s formal intuition would prove profoundly true in the years to come. As the non-fictional novel became popular, it grew increasingly clear that testimony is as intellectually challenging for a writer as fiction. And of course, it is rewarding for a reader. Years later, in 2006, US writer Joan Didion would observe that “writing nonfiction is more like sculpture, a matter of shaping the research into the finished thing”. But there was more to Walsh’s literary choices than a simple aesthetic preference. Indeed, aesthetics were his least minor concern.

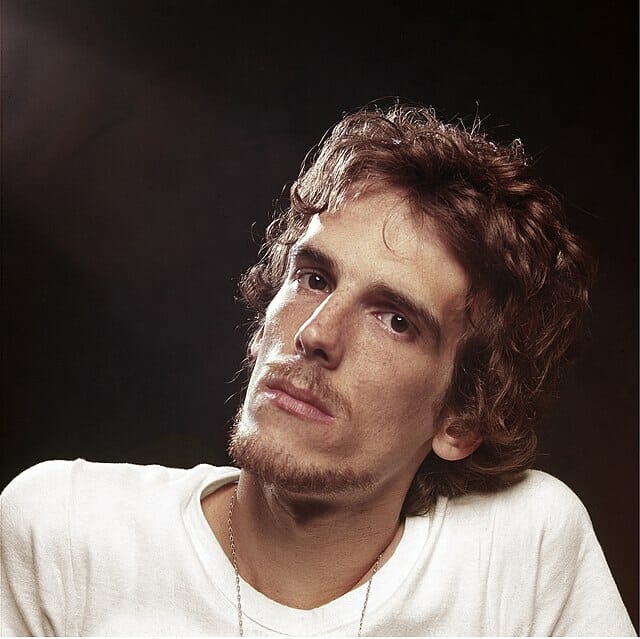

Rodolfo Walsh: the anti-Borges

Soon after he rose to literary fame, Walsh was labelled the “anti-Borges” by some contemporary critics. His style, they thought, was too popular and straightforward. Against the Borgesian pursuit of formal perfection, Walsh was mainly interested in having an impact on reality.

It took me a long time to realise that the things that need to be told are so many and so urgent that you don’t have to stop and look at how you tell them

Rodolfo Walsh, in a note from his diary

Thus, ever since the 1955 coup that overthrew Perón, Walsh struggled to find a balance between his literary vocation and the urge to do something politically impactful. Operación Masacre is the first product of this reflection. Could he just sit there writing crime novels as his country sank in a real spiral of violence? He concluded that it would be unacceptable. The claim that literature should be unpolitical was not only a misunderstanding of its place in the world, but a perversion of the very purpose of art. According to Walsh, it would “take away from art all its dangerousness, its action over life, its direct and real influence over life at that moment”.

Eventually, Walsh concluded that the novel was the expression of a particular time and social class. It could only represent bourgeois problems. And turning to non-fiction was the only way to emancipate literature from this ideological cage.

A great warning cry

Over the last few years, the political orientation of non-fictional literature proved more ambiguous than Walsh’s expectations. The work of Emmanuel Carrère made it clear that testimony can be just as bourgeois as any other literary form. But Walsh’s unrepeatable bravery is still what makes his work so valuable. And his vision remains as inspiring as it was seventy years ago.

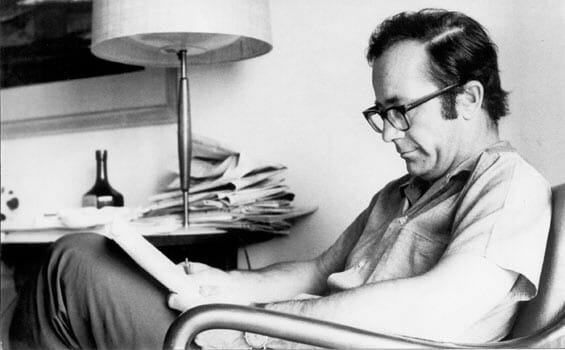

The courage and the altruism that inform Operación Masacre are excruciating. Readers are constantly moved to question themselves. How far would I go in the name of freedom? At what point would I give up? Such a point, Walsh could never reach. In an introduction to a 1972 edition of the book, Argentinian writer and journalist Osvaldo Bayer defined Operación Masacre as “the great warning cry” – the prologue of the tragedy that will follow.

Indeed, throughout his lifetime, Walsh kept fighting for the truth, as he did with Operación Masacre. And not even the greatest assaults on freedom could shake his faith in the dangerousness of art. On March 24, 1977, he published the Carta abierta de un escritor a la Junta Militar (Open letter from a writer to the Military Junta), a ferocious critique of Videla’s regime.

Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez played a key role in spreading the letter, which he called “a masterpiece of journalism”. Walsh couldn’t find a greater endorsement for his idea of testimony as a form of art. Yet, the price to pay was enormous. He disappeared the day after the publication of the letter, joining the 30.000 Argentinians who became desaparecidos between 1976 and 1983. But he recounted it all, until the very last day. And made of himself the protagonist of his own lifelong tragedy.

Tag