Soldiers of Salamis | A writer’s version

Author

Year

Format

Up until the publication of Soldiers of Salamis, in 2001, there was only one known version of the story of Rafael Sánchez Mazas’ execution. The story had been told a thousand times in the ’40s but was now forgotten by most. Sánchez Mazas was a writer, a close collaborator of José Antonio Primo de Riveira and one of the key idealists of the Falange Española. For most of his life, he stood with the power, but there was a moment he was totally helpless.

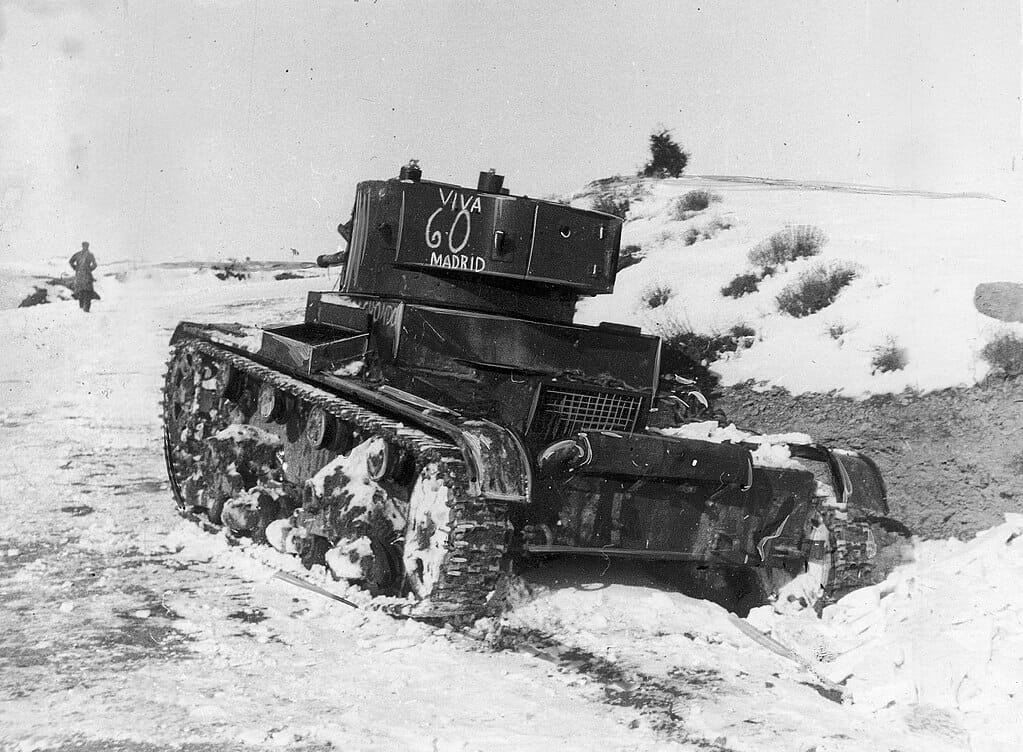

The story went like this. In winter 1937, in the middle of the Spanish civil war, Sánchez Mazas left the Chilean embassy where he was living as a refugee and headed to Barcelona. Here, he was arrested and deported to the Collell, an old sanctuary close to the French border. After a few days of detention, he survived a mass execution and hid in the woods, where he was soon found by a republican soldier. For unknown reasons, the man spared his life and let him escape. Sánchez Mazas, however, often omitted this part when he told the story in public.

When Spanish writer Javier Cercas first heard about it, the story was nothing more than a forgotten piece of fascist propaganda. Yet, he managed to turn it into a best-selling novel. But even with its apparently remote setting, Soldiers of Salamis is far from being a historical novel. Ultimately, it tells the story of how Cercas tries to make sense of that episode by putting it into a new perspective, and here lies its strength.

A matter of perspective

There are three sections that make up Soldiers of Salamis. In the first one, a fictionalized Cercas hears about the story of the execution and decides to write a novel about it. The second section takes place during the war itself, and it revolves around Sánchez Mazas’s life and execution. Here, in an attempt to understand what animated the Falangist movement, the author presents Sánchez Mazas in all his human complexity. In the third and final section, Cercas has finished the novel, but he is completely unhappy with it. Something is missing, maybe the very core of the story. The writer realizes what it is only by chance.

Following a series of leads, he comes into contact with an old man named Miralles, and comes to believe that he is the soldier who saved Sánchez Mazas from execution. It becomes clear, then, that what the story was missing was a reason for it to be told again. Once he meets Miralles, Cercas finally realizes what his real motivation has always been.

If it’s true that behind every good book there is a good question, the one behind Soldiers of Salamis is simply haunting. As Cercas writes in the first chapter,

“We’ll never know who that militiaman was who spared Sánchez Mazas’ life, nor what passed through his mind when he looked him in the eye […]. I think, if we managed to unveil one of these parallel secrets, we might perhaps also touch on a much more essential secret.”

Thus, while he might look like a minor character at first, the real heroes of Soldiers of Salamis are Miralles and his possible alter ego, the unknown soldier.

The past is never past

By changing the focus of the story, Cercas manages to turn an apparently remote episode into a vibrant reality. As he once declared, “The past, and especially the past of which there is witness, of which there is memory, has not yet passed. It is a dimension of the present, without which the present is mutilated”. This is why keeping it alive is not just a worthwhile practice. It is an effort that has to be made.

When, in the third chapter, the author finally meets Miralles, the need for such an effort becomes evident. At the beginning of the novel, men like the unknown soldier seemed as distant as soldiers of Salamis. But there stands Miralles, disfigured by scars, forgotten by all, spending his last years in a hospice where no one visits him. No one ever thanked him for the battles he fought, and he doesn’t expect this to happen. What he finds unacceptable, though, is that his dead fellows’ destiny is oblivion too.

It doesn’t matter whether he really is the unknown soldier or not (the mystery, as most good mysteries, remains unsolved). Still, he stands as a symbol of a whole generation’s forgotten sufferings. Soldiers like Miralles finally find redemption in the novel’s ending, a beautifully lyrical ode to war heroes.

“It breathes literature through all of its pores...”

Cercas probably could understand what it means to lack recognition. When he was working on Soldiers of Salamis, he had already published four novels, but his readers were even a niche. Yet, once his fifth novel came out, he suddenly rose to literary stardom. Writers of the caliber of J.M. Coetzee, Susan Sontag, and Mario Vargas Llosa showed absolute enthusiasm about it. Indeed, the latter’s review was determinant for Soldiers of Salamis’ success. “This book, which boasts so much of not fantasizing, of sticking to what is strictly proven, in truth breathes literature through all its pores”, he wrote in his column on El País.

In Soldiers of Salamis, Cercas manages to bring back to life a trite anecdote about a fascist’s execution, but his success has nothing to do with the reconstruction of the episode itself — rather, with the means of the reconstruction. For the first time, the story was approached from the most vivid perspective possible: that of literature. The spirit of redemption of the last chapter would have been impossible otherwise. In fact, Cercas slightly changed Miralles’ story and the unknown soldier’s one as well.

The writer’s version

The choice to give a literary adaptation to the story of Sánchez Mazas’ execution had its risks too. Cercas’ decision to have a fascist as the apparent protagonist of his book met with dismay from some critics. Yet, it was due. “I have tried to present it in the most complex way possible, which is the mission of art […],” he explained in an interview. His moral stance is clear: to fully understand the past, it is crucial to be as close to it as possible. The fact that he appears as a character in the novel serves this very purpose. He is a knot between the present and the past.

Over the years, Cercas made this a real trademark. Some critics have called this style literary transparency, as the process of writing becomes part of the novel itself. Cercas’ merit, indeed, really has something to do with the clearness of his sight. In Soldiers of Salamis, he managed to make obvious the only part of the story that had so far been invisible. And it doesn’t matter if the ending is fictional: the only thing that matters is that Miralles finally finds recognition. This is, ultimately, what literature has always been for — because stories matter, but what matters is the way they are told.

Tag