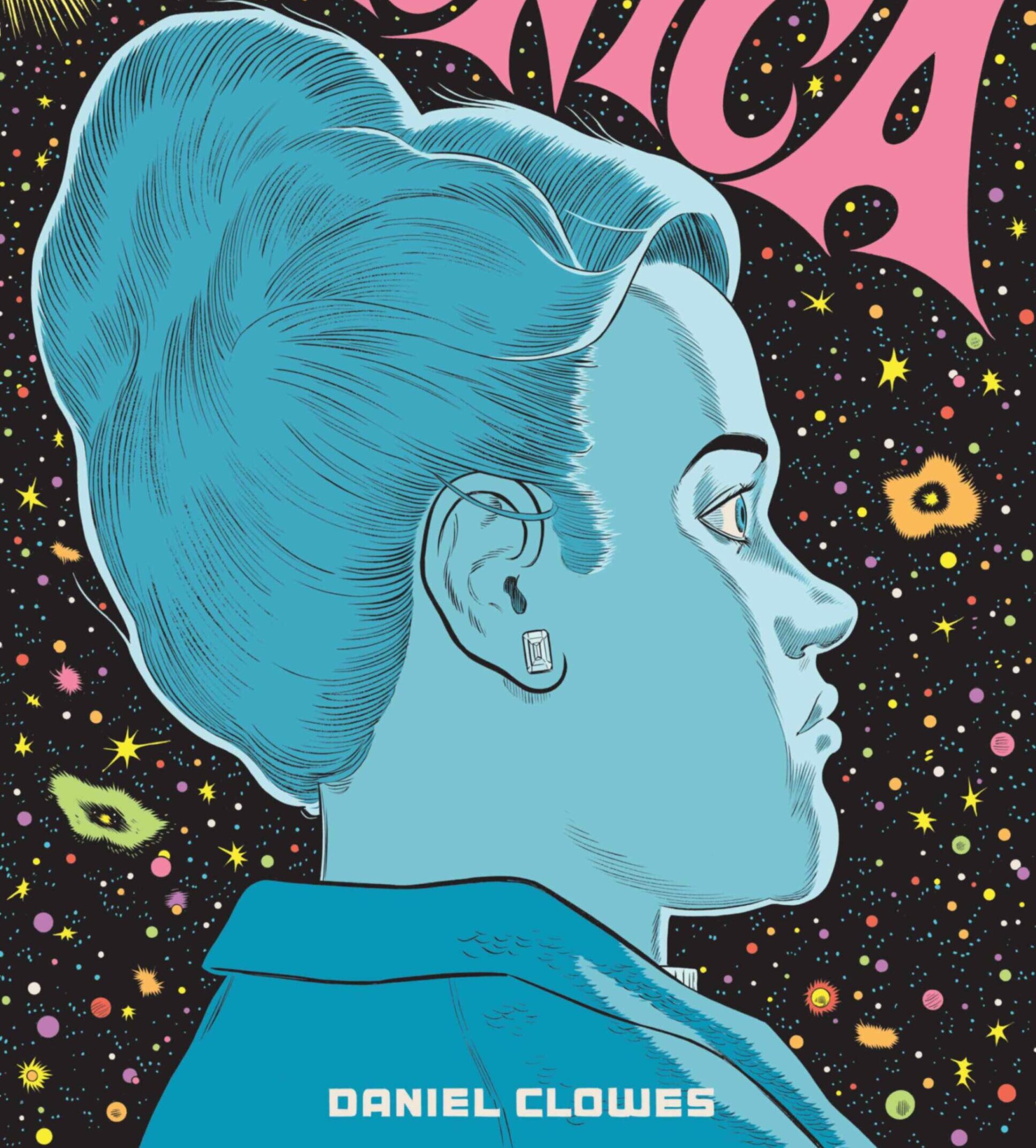

Monica, by Daniel Clowes | Life is a discovery that cannot be trusted

Author

Year

Format

By

Throughout life, everyone has faced various challenges, whether large or small: the fear of abandonment – or abandonment itself -, the discovery of one’s own identity or the encounter with the sometimes mysterious and scary outside world. Monica, the protagonist of Daniel Clowes‘ latest graphic novel, faces all of them.

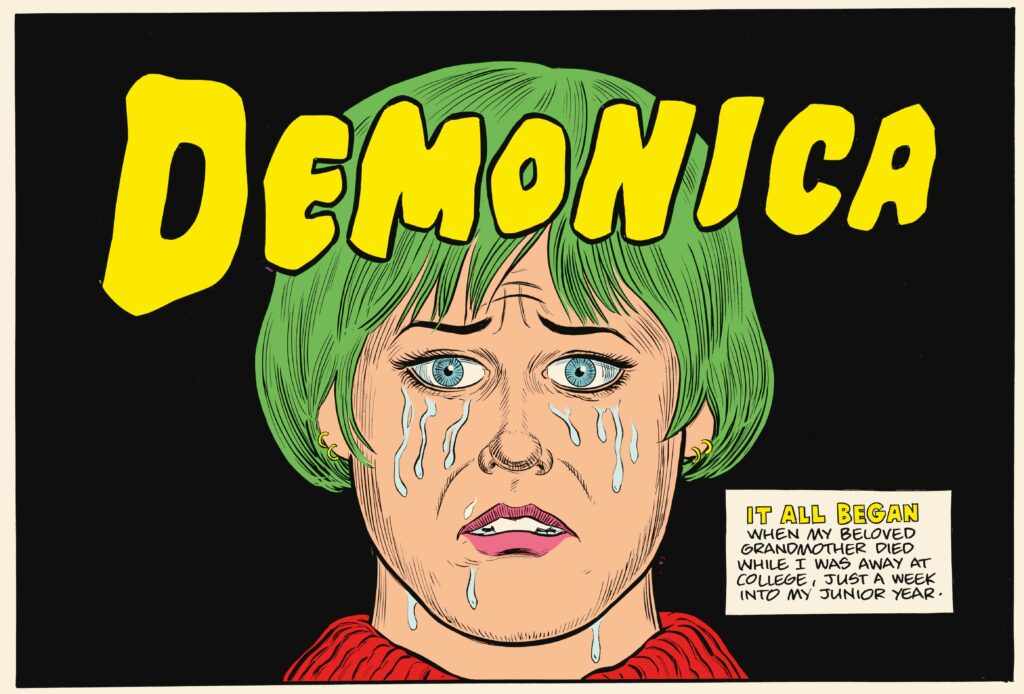

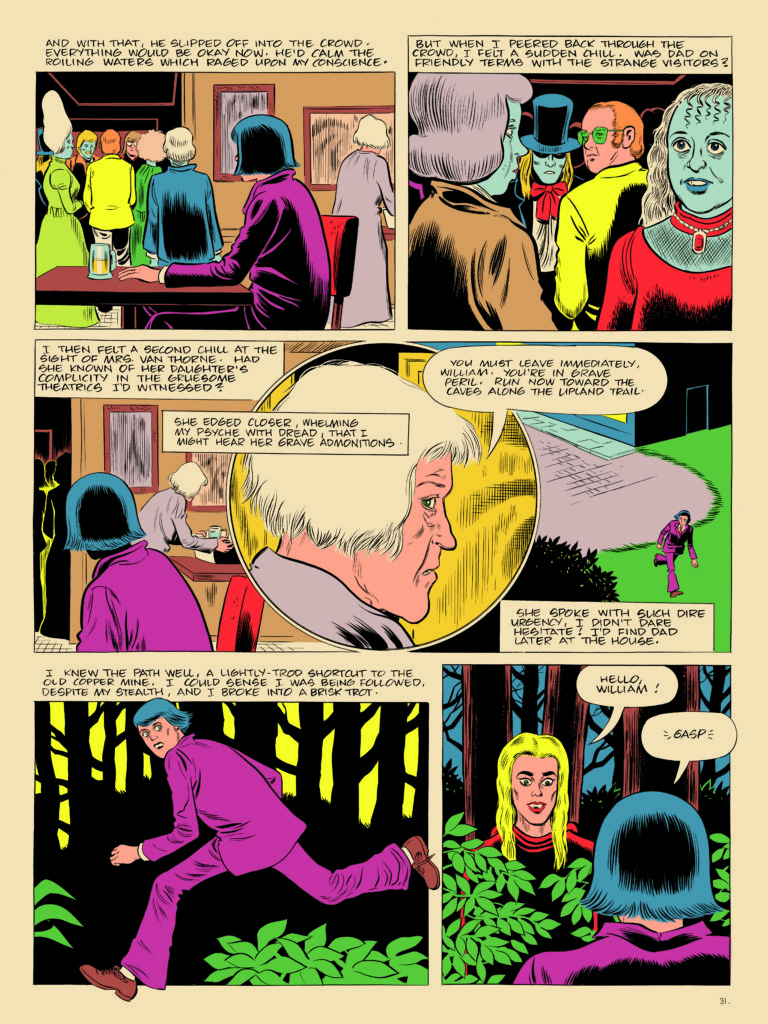

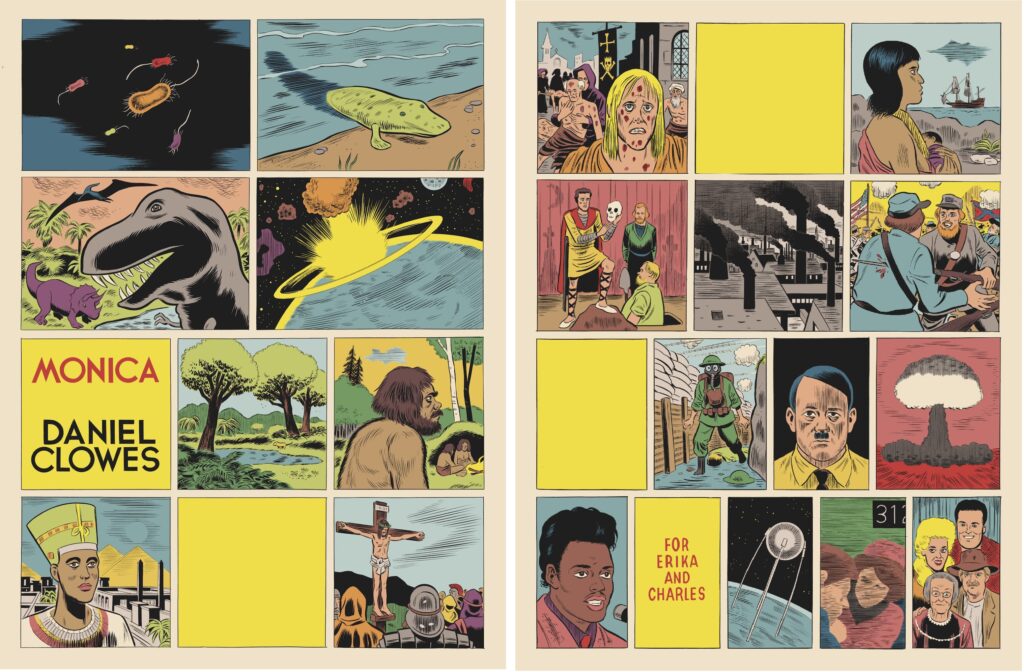

The narrative is divided into nine chapters, which are also nine stories that do not always have Monica as the protagonist. They all mean to describe the world in which Monica lives, makes mistakes and discoveries, a world which intertwines drama, horror and science fiction.

Identity as Evolution

The story begins in Vietnam, during the war, with two soldiers. Then it moves to California, where Penny, the girlfriend of one of the two soldiers, immerses herself in hippie culture. Monica is Penny’s daughter, and she becomes the key through which readers explore the movement and the problems of what was the new generation of those times.

Monica, initially presented as a child, faces a growth marked by her mother’s abandonment. After the death of her grandparents, she sets off in search of both his mother’s and his father’s identity. A path that could even recall that of The Boy and The Heron by Hayao Miyazaki.

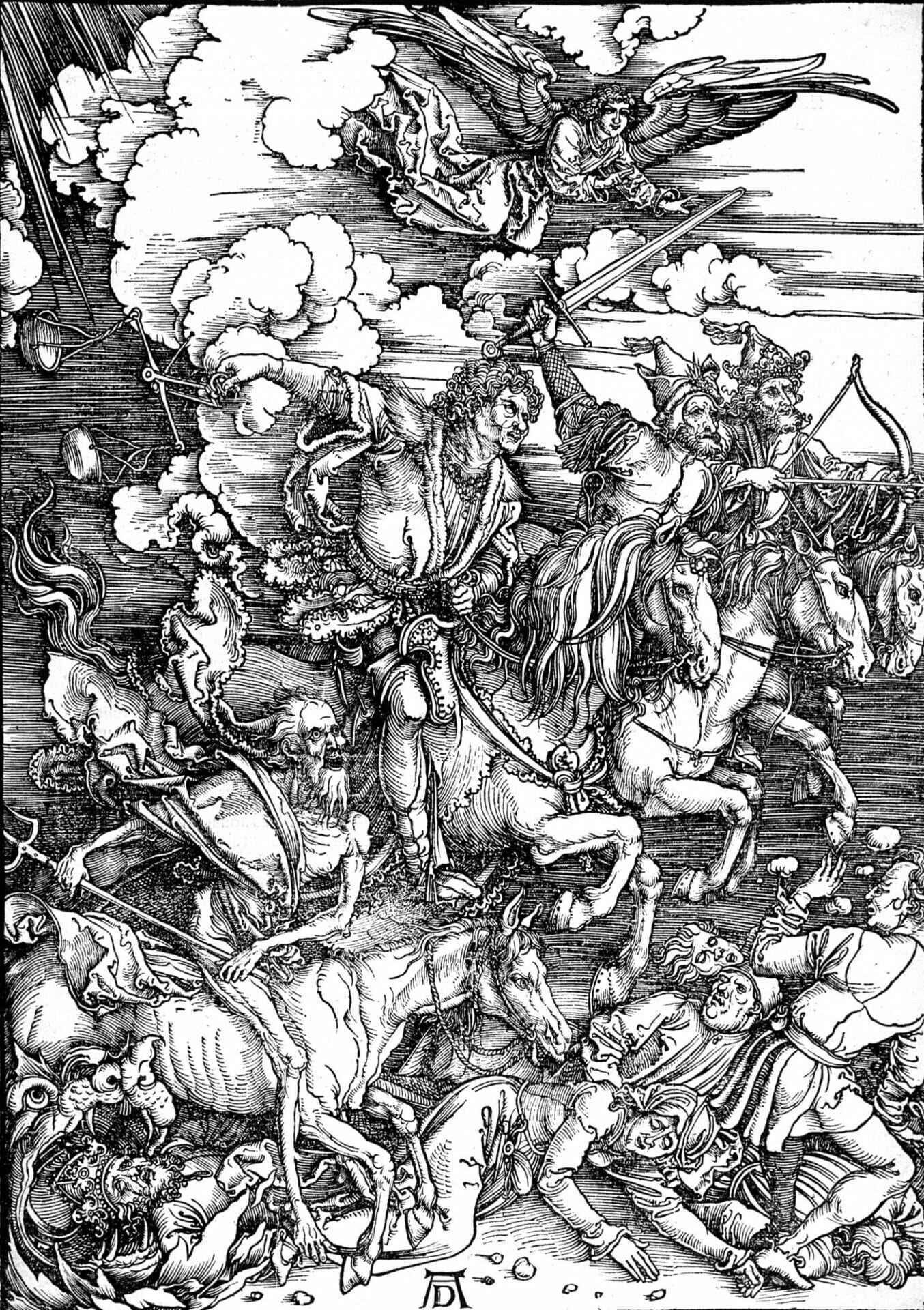

The plot unfolds by introducing supernatural and demonic elements into everyday life. The story, anchored between reality and fantasy, evolves with an apocalyptic vision of life, humanity and history, exploring the end-of-the-world and transcendence fantasies of the counterculture.

In her research, Monica deals with ritual sacrifices, cults and communications with the dead, highlighting an America in evolution which however seems almost afraid of itself. A country that is reflected in Monica: the issues she brings with her, such as abandonment, the search for identity and generational challenges, highlight precisely the attempt to want to emerge as individuals in a society that pushes everyone, despite feeling different, to conform to someone or something.

Monica’s story is also a bit like the story of the whole of humanity, which often mistakenly believes it has understood everything. She lives her adventures to discover her father’s identity, so as to be able to give a true one to herself too, then realizing, only at the end, that she is ultimately part of a much larger mechanism that she hadn’t even considered at all.

The sense of paranoia

Daniel Clowes, in developing Monica, returns with a strong female protagonist, on a par with the women in his other famous works such as Ghost World and Patience. In Monica, the author draws inspiration from various visual sources, not necessarily used in fundamental moments of the opera, but rather to pay homage to the authors of the past who contributed to his formation. He does that by drawing a character with the same features as that of another artist or with those of the artist himself. In particular, for some atmospheres he takes inspiration from Joe Orlando: his Midnight Mess!, published in Tales from the Crypt, is a reference on the metaphor of the adolescent experience of navigating a world full of unseen dangers.

Joe Orlando is not an artist I particularly admire. […] But I wanted to make a nod to his story and reference his sense of paranoia. […] You might have felt that way about entering a small town. Nowadays, there aren’t as many places where you feel such a sense of alienation.

Daniel Clowes to The New Yorker

The visual language, typical of Clowes, with rounded figures, minimal backgrounds and saturated colors, reflects the 1940s aesthetic of EC Comics, a publishing house famous for its horror and crime stories, offering a nod to a bygone era and integrating perfectly with the different comic genres present. Clowes creates an atmosphere of pulpy nightmare, where seemingly banal boredom gradually transforms into visceral horror. Each period, whether it is delving into the Vietnam War or exploring the heights of female success, hides a hint of restlessness that Clowes expresses, on the contrary, with an excess of colors and bright tones.

Pretending

After the opening story, “Foxhole,” which looks like a classic war story, I wanted to segue into a story that looked more like a romance comic. I love the idea of romance comics: they were aimed at teen-age girls, but were mostly written and drawn by older men thinking that they knew what girls wanted. They include advice columns, like “Dear Doris”—but “Doris” is often an old man sitting in an office somewhere, pretending to care. I wanted to capture such a bizarre reflection of reality.

Daniel Clowes to The New Yorker

Monica is also a bit of all this. As in the situation Clowes is referring to, such as the old man pretending to be a woman, nobody ever knows who they can trust. Sometimes one can’t even trust themselves.

Throughout her life, Monica has imagined scenarios and beliefs that she developed regarding her parents’ fate. She felt like the investigator trying to weave together the threads of a mystery, managing to reach a conclusion – perhaps not totally satisfactory – but which in some way allows her to close a chapter of her life.

Clowes suggests, however, that Monica has not understood everything at all. She is not the heroine she thinks she is, despite her many adventures. There are things bigger than her, mysteries that she cannot solve, and Monica is no more special than the others, she is just a cog in that mechanism that is History and which will go on anyway, with or without her.

Monica is not so much a journey, then, in search of her lost father and mother, but rather a journey into the mind and beliefs of Monica herself, and how, to deal with her traumas, has managed to build an entire world on her own.

Monica becomes also passionate about writing, and writes stories which she never talks about. Maybe, in reality, some of the chapters in the graphic novel are the stories written by Monica. Therefore, even in this case, some elements, which could only be the result of Fantasy, must be separated from the Truth.

The reader has still the task of distinguishing the two factions, and given the ending of the graphic novel, might think that destiny is only destruction, the failure of every search, but Clowes himself invites everyone to investigate the pages of the book themselves and to look for hidden nuances, to understand where lie the lies, the imagination, and where the truth. As long as there actually is one.

A nod to the past

In more than one interview Clowes declared that Monica is also a bit of a part of himself, with real autobiographical insights. The author did not find himself part of a cult and did not hear his deceased grandfather’s voice coming from a radio, but he too had a childhood characterized by the lack of presence of his parental figures. As he said in an interview for NPR, his mother also left him with his grandparents, leaving him behind so she could live her dream of running an auto repair shop.

Monica was published by Fantagraphics at the end of 2023, and The New York Times has included the comics in the list of the Notable Books of 2023. With this graphic novel, Clowes moves another step forward into the analysis of how difficult and unsettling can be to deal with the outside world and our inner self.

Tag