Stacy, Gipi's graphic novel | The backlash of modern society

Author

Year

Format

By

In Arthur Miller‘s classic The Crucible (1953), collective paranoia turns into witch hunts. In Adaptation (2002), by Charlie Kaufman, the author reflects on the nature of art itself, suggesting that the artistic insecurity of the protagonist (Nicholas Cage) is fuelled both by external pressures, and from his personal insecurities.

With his graphic novel Stacy, Gipi does the same, immersing himself in a similar theme. The protagonist, Gianni, faces public shame for a theoretically insignificant event, and at the same time reflects on why he was unable to adequately deal with the criticism, showing himself, rather, than still depending on others. Telling this story, the author addresses the theme of cancel culture.

After a period of retirement from the scene, Gianni Pacinotti (Gipi’s real name) returns in 2023 with Stacy, published by Coconino Press, to personally respond to a controversy that involved him in 2021, thus giving his own artistic and personal vision on what happened.

“Stacy is buttery”

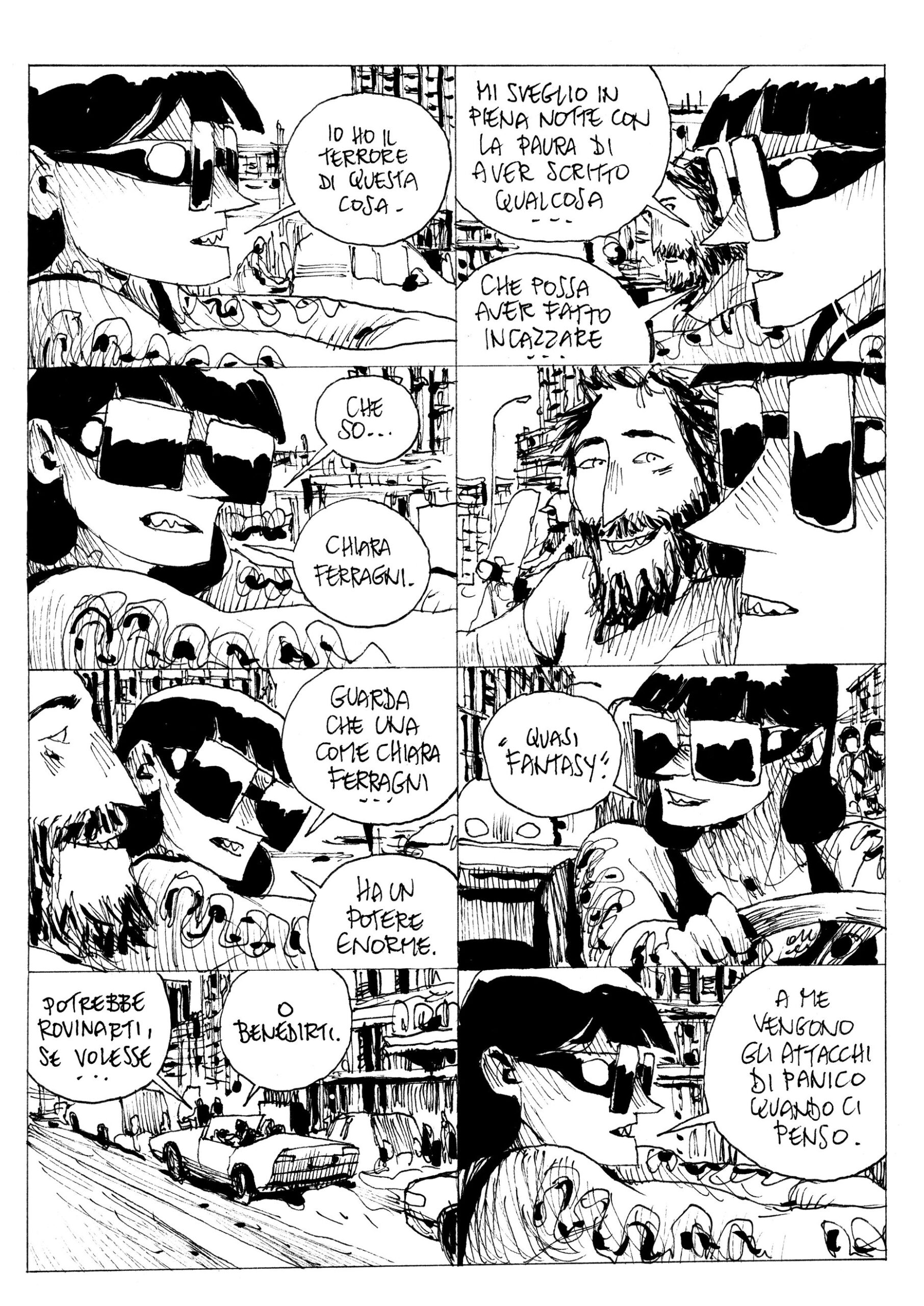

Gianni is a writer and screenwriter of successful TV shows. During a seemingly harmless interview, Gianni utters three words, relating to a dream in which he imagined he was torturing a girl, which become the subject of discussions on social networks: Stacy is buttery.

The obsession with this mysterious, yet imaginary, Stacy grows more and more, until it almost becomes a therapy, a catharsis: the creative and imaginative effort aimed at unloading, sublimating and overcoming an experience that is devastating in its own way. The reader never sees a full figure of her, because, simply, she exists only in Gianni’s mind. But Gianni creates also someone else: his alter ego, a demon. His resentful side, eager for revenge, takes physical shape.

Stacy thus becomes a narrative of radicalization, in which Gianni confronts his naivety, unable to face the disproportionate consequences of his actions and the betrayal of those he trusted.

Stacy, © Gipi / © for the Italian edition Coconino Press – Fandango, 2023

Gipi’s way of responding to critics

In Stacy there emerges an attack towards the controversies sparked by cancel culture, something which now occurs in modern society. The protagonist Gianni is pilloried for having told a dream, and the same thing happened to the-author-Gianni for a comic published on Instagram, in which it was highlighted that the concept “Believe all women” could have some logical fallacies.

What happens to Gianni, in Stacy, is estrangement from his job and exclusion from the colleagues he had considered friends. The latter could not support him, because political correctness doesn’t allow it.

Cancel culture and political correctness go hand in hand, and Gipi stresses the point to the extreme when, during the development of a TV show, Gianni and his team find themselves with the dilemma of who to use to dub a parrot without offending the feelings of the animal itself.

These dynamics, therefore, affect not only human relationships, but also the very concept of art, which should be free from constraints. Gipi underlines the fact that an artist should be, by definition, free to express himself and experiment, while nowadays, thanks to the immediacy of social networks and the superficiality of judgment that they often promote, people tend to see everything in black and white: if someone deviates from a socially established binary, then they are not worthy of having their own voice. This undermines the authenticity of the art itself, because it’s no longer free, but rather caged by social rules.

Stacy‘s Gianni, although readmitted to the winners’ circle at a certain point, does not go back to being what he was before. Although pillorying can be explosive but very short, it leaves a trace, while those who carry it out forget about it within a few days. Gianni changes, bringing out the darkest side of himself as a consequence: he becomes the demon alter ego that his mind has created. It’s the phenomenon of backlash, which leads individuals, as a reaction, to slide towards extremism, thus causing even more moralization on the part of others, and therefore perpetuating a vicious circle in which the law of the strongest prevails.

Zerocalcare says This world won’t make me bad, but for Gipi it seems absolutely the opposite.

The lack of empathy through style

Stacy was born from the anger I’ve been filled with for months. It was strange, because the pain – if we can talk about pain – only came from people I knew personally, who had essentially stabbed me in the back for social and work positioning opportunities. Those hurt me.

Gipi in an interview for Daniele Rielli‘s podcast

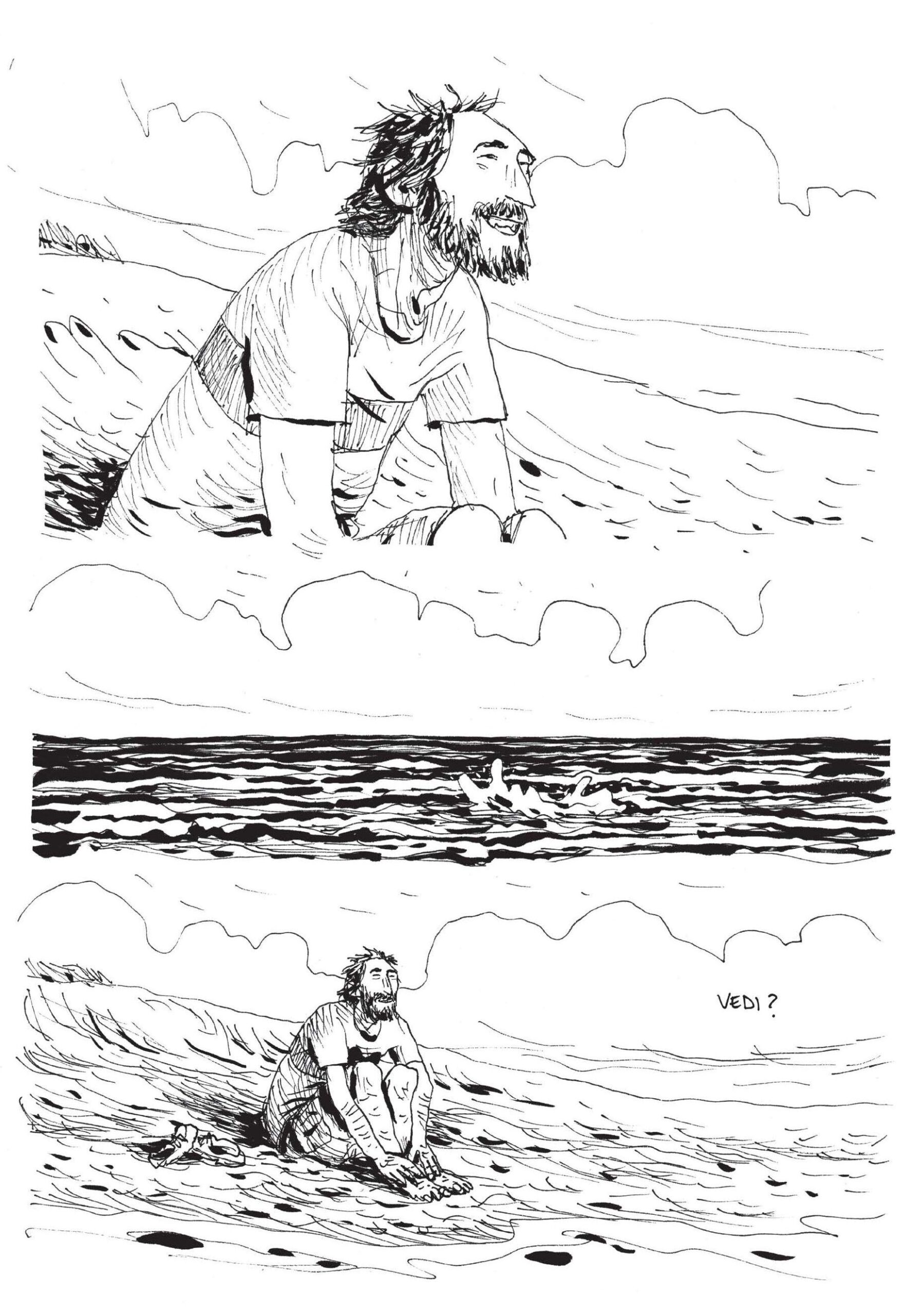

The style of Stacy is insistent and obsessive, with elements that return with pounding frequency. The name Stacy abounds in the dialogues and title pages that punctuate the story, while the rigidity of the page, with a grid with eight full panels, contributes to creating a sense of oppression and anguish. The use of black and white is predominant: it transmits a dark grayness in harmony with the unpleasant and desolate theme of the work.

Stacy, © Gipi / © for the Italian edition Coconino Press – Fandango, 2023

Stylistically, Stacy is a bit like another Gipi’s work, The Land of Children: without watercolors, in black and white as well, while narratively it presents itself as a cross between a biographical story and a Fincherian thriller, full of biting jokes and mischievous that reflect the hypocrisy and dark impulses of man.

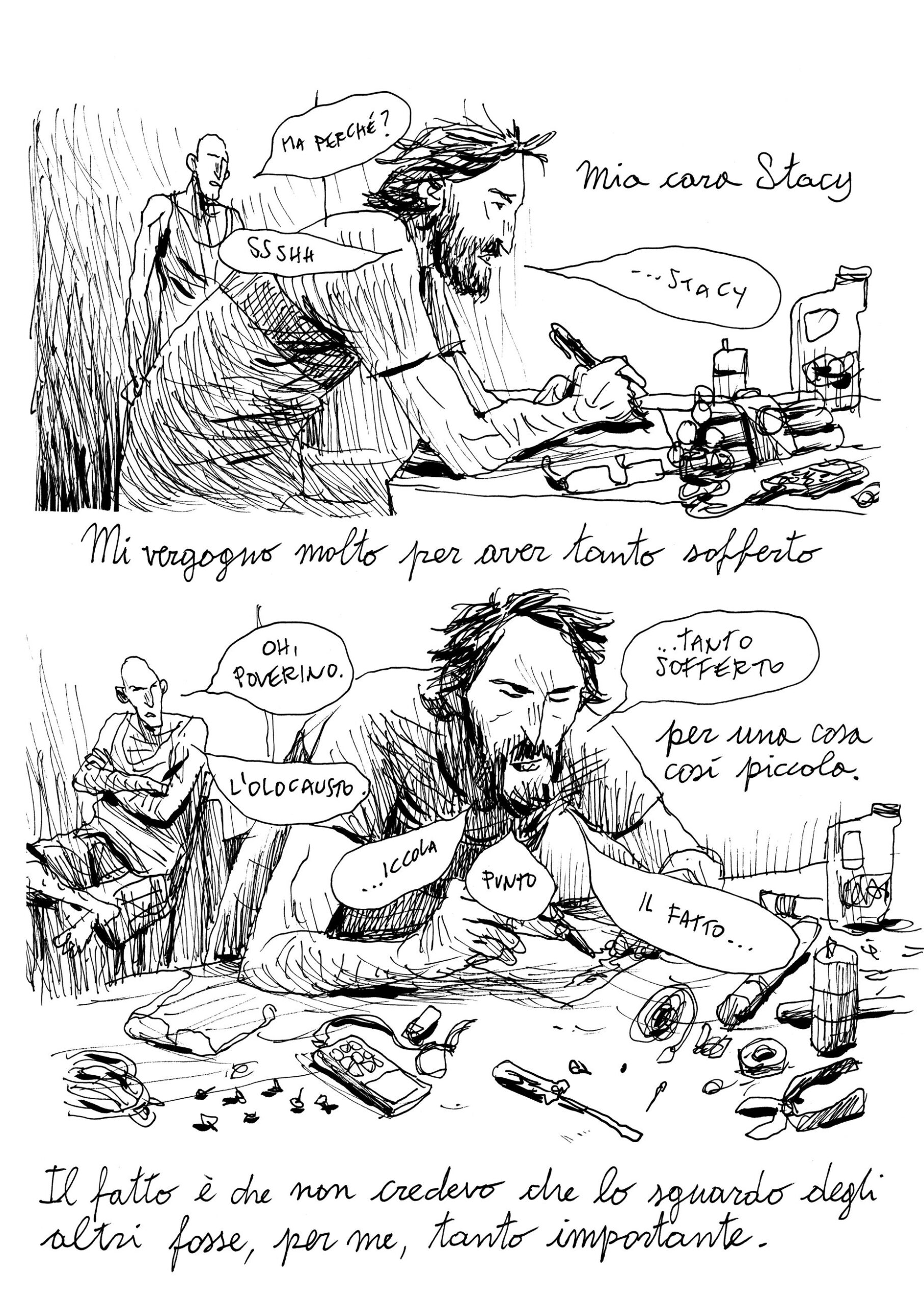

Gipi’s drawings are nervous and essential, with a biting stylization that permeates even the representations of smiles with anguish. During the narration, readers often find pages with entire texts written by Gipi himself, rather than lines spoken by the characters in their balloons, while drawings in these cases become increasingly rare. They look like pages from a personal diary, and it is as if readers, in this way, enter deeper into the mind of the author himself.

Demon: But why? Gianni: Ssshhh… Stacy

“I am very ashamed for having suffered so much”

Demon: Oh, poor thing. Gianni: … suffered so much

“for such a small thing,”

Demon: … the holocaust. Gianni: … ing / Full stop / The fact…

“The fact is that I didn’t believe that the gaze of others was so important to me.”

Stacy, © Gipi / © for the Italian edition Coconino Press – Fandango, 2023

In other parts, not only is the story just text, but it is in a script-form, therefore without even Gipi’s handwriting. These parts describe in particular some key elements of the relationship between Gianni and the demon, until it is clear that the two are the same person. A screenplay expresses the emotion of the story, but is written in a formal and aseptic manner, following precise rules. It is as if in these parts of Stacy the harsh truth and nothing else comes out, without being embellished by any empathy: demons exist, men simply hide them.

“You can’t talk about Stacy”

The first rule of Fight Club is you do not talk about Fight Club.

Fight Club (1999), by David Fincher

I solemnly promise that I will never talk about Stacy.

Gianni in Stacy

With Stacy, Gipi transforms his resentment into art, a cryptic journey into the contradictions of modern man, demonstrating that there are still spaces for freedom of expression.

Stacy, © Gipi / © for the Italian edition Coconino Press – Fandango, 2023

Stacy therefore becomes the imaginary figure that binds the most ambiguous part of anyone, the one that they try to keep hidden for fear of other people’s judgment. At the same time, though, it is the refuge from the torment of increasingly becoming too equal to each other, clones in a society where nobody can talk about Stacy. But that doesn’t mean Stacy doesn’t exist.

Tag