Alien | Fear Is in the Eye of the Beholder

Runtime

“In space no one can hear you scream.” So reads the tagline of this sci-fi/horror milestone, that immediately sums up the state of terror and isolation that permeates Ridley Scott‘s movie. A straightforward but also layered narrative, Alien provides the viewer with multiple possible interpretations, along with a ride to a house of horrors set in outer space.

In the depths of the universe, the cargo starship Nostromo receives what seems to be an incoming SOS from an unknown planet. The crew (five men, two women, and a cat) track the signal to an abandoned alien spacecraft. When a mysterious parasite attaches itself to one of the astronauts, a nightmare is about to break loose: an indestructible alien with acid for blood has just boarded the ship, and it soon starts killing the crew one by one.

An A-list B-movie

I don’t want to make it a more important film. I want it to be a straightforward, unpretentious, riveting thriller, like Psycho or Rosemary’s Baby. But I want it to look like, and I’m going to make it look like, 2001.

Director Ridley Scott in an interview reported in J. W. Rinzler‘s The Making of Alien

Despite the $11 million dollar budget of an A-list production, Alien is, at its core, a B-list movie. Or at least that was the intention of original screenwriters Ronald Shusett and Dan O’Bannon. The latter had just finished working on John Carpenter‘s debut Dark Star (1974) – a low-budget, satirical sci-fi cult classic – and both screenwriters intended to follow its trail. Their script assimilates and reprocesses the long tradition of 1950s sci-fi/horror while also gathering influences from genre literature.

The one-by-one killing spree at the hands of an invisible murderer, and the progressive isolation that ensues, mirrors Agatha Christie‘s And Then There Were None. The hovering of H. P. Lovecraft, father of the cosmic horror subgenre, is constant. Even the oldest monster in English Literature plays its part: the alien’s acid blood originally belonged to Grendel, from the epic poem Beowulf.

What made Alien ‘A-list’ though is not just the large investment. It is the seriousness with which the task of instilling fear was treated, rather than the subject matter itself. In horror, Ridley Scott saw a challenge in pushing terror as close to the viewer as possible, as did the instant classics The Exorcist (1972) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974). In science fiction, he saw a chance to showcase the visual prowess he had mastered in his years as a commercial director. And he would continue on this path with his next movie, another sci-fi classic: Blade Runner (1982).

This patch-working proved to be successful. Alien inevitably started a thread (Carpenter’s 1982 remake of The Thing is a very similar operation), as its intuitions and innovations breathed new life into all the genres involved.

Working class from outer space

One innovation lies in the characters. In later (uncredited) drafts of the script, Walter Hill and David Giler rewrote the astronauts as “truckers in space”. “Not adventurers but workers” (as critic Roger Ebert noted) with whom the viewer could more easily identify. Social commentary quickly joined in.

Inspired by the corporate thriller subgenre of the 1970s (Giler co-wrote Alan J. Pakula‘s 1974 conspiracy movie The Parallax View), the two added an element of paranoia to the already suspenseful story. In their fight for survival, the now class-divided astronauts must also keep an eye on the omnipotent company that hired them. The only people who might hear them scream will not, or they cannot be trusted anyway.

As the crew gets tighter and the war of nerves ensue, it becomes increasingly difficult for the viewer to figure out who is who. And most importantly, who will make it out alive in the end.

The girl who knew how to fight

The outcome, at the time, was quite surprising. The hero/damsel-in-distress dynamic is turned upside down. Men are now inept and the only one capable of taking charge and fighting the monster is a girl. Played by newcomer Sigourney Weaver, the female lead (yet another Giler and Hill idea) moves away from the final girl trope that was rampant in the 1970s (Sally Hardesty from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre appeared in 1974, and Laurie Strode from Halloween in 1978).

Alien‘s Ellen Ripley does not merely survive. She shows resilience, courage, self-control, and leadership. Virtues that at the time, on screen, traditionally and stereotypically belonged almost exclusively to men. She asserted herself not only in the movie but in the entire realm of action and thriller.

After her, it was easier for other heroines to stand out in tension pieces, most of which still target a predominantly male viewership with male heroes (Sarah Connor from the Terminator saga owes much to Ellen Ripley). Given the winning bet, Weaver would return in the three inevitable sequels: James Cameron‘s Aliens (1986), David Fincher‘s Alien 3 (1992), and Jean-Pierre Jeunet‘s Alien Resurrection (1997). But that is another story.

A design that came from within

Another main reason for the movie’s fortune is the titular alien and its peculiar conception. The plot revolves around its murderous life cycle, which twists sexuality, pregnancy, and birth into monstrosity. With its violence and urge to reproduce, the alien takes human impulses to their extreme consequences.

The aim is clear: to hit the most sensitive part of the viewer. To pervert what they find familiar and reassuring until they fear it. To turn their own physical instincts against them. It’s the quintessence of body horror. The subgenre was just developing under the wing of David Cronenberg with movies like They Came from Within (1975) and The Brood (1979). And Alien soon became a benchmark for it.

Unlike Cronenberg, however, Scott could not afford to show such horrors head-on. If he wanted to reach a mass viewership, he had to ditch the potentially repulsive elements lurking in the script. He had to make a virtue of the need for subtlety. He had to rely on an objective correlative, which he found in the bio-mechanical design of the alien’s anatomy and homeworld.

The mastermind behind this imagery is the Swiss painter H. R. Giger (whom O’Bannon met during the pre-production of Jodorowsky‘s aborted Dune). The artist soon learned the lesson of Hieronymus Bosch, Antoni Gaudí, Alfred Kubin, and Francis Bacon. By pouring the innermost visions that haunted him onto canvas, Giger soon reached a vivid, idiosyncratic, neo-surrealist aesthetic. And the perfect fit for the task of carrying out the story’s Eros-Thanatos innuendos. Giger’s design from within instantly crawled under the viewer’s skin and into the collective memory and has not left since.

A nightmare within a dream

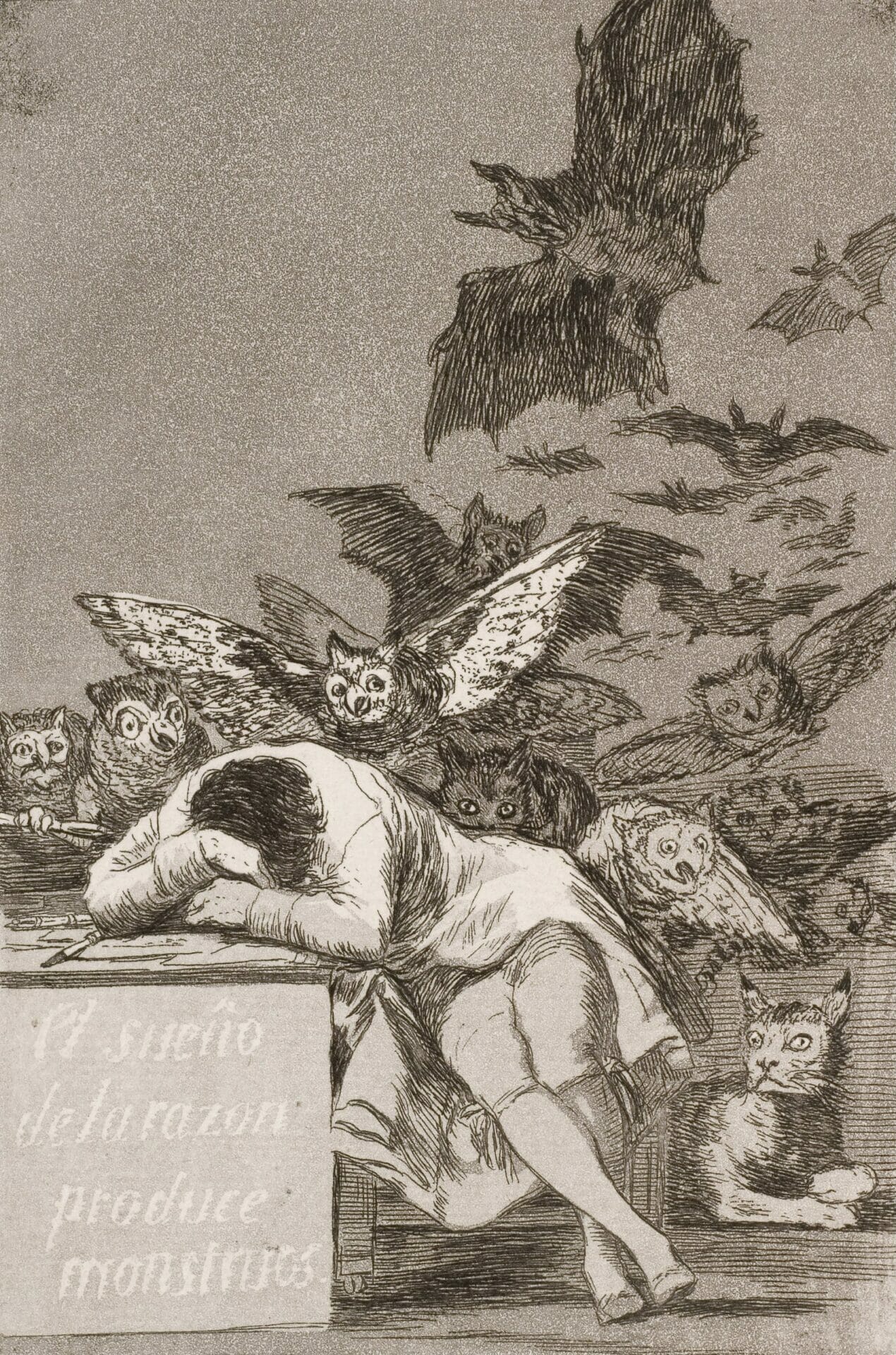

Curiously enough, in O’Bannon’s earliest draft of the screenplay, the alien was downright abstract. The monster served as an embodiment of the Id, the instinctual side of personality that lurks beneath the rational one. Despite the many rewrites and Giger’s very physical design, the metaphor still stands.

The alien embodies the fear of the dark and the unknown. The crew cannot think of a way to kill the indestructible creature because reason is useless against a monster that goes beyond it. Its very sight is paralyzing to them. Still, they will have to bear it. They will face terror personified, as if in a nightmare.

The oniric nature of the plot would have been even clearer with the quote that was supposed to open the movie:

We live, as we dream – alone.

from Joseph Conrad‘s Heart of Darkness

After all, the movie begins and ends with the characters waking from and going into hyper-sleep. Is their whole ordeal a nightmarish parenthesis inside an outer space dream?

“All that we see or seem. Is but a dream within a dream”, one might reply, quoting Edgar Allan Poe‘s poem about the vanity of all things. In this sense, the fact that “in space no one can hear you scream” is not just a matter of terror and isolation. It is about how meaningless the characters’ sorrow is, in comparison to the immensity of the universe. It is a cosmic horror recurring theme, and it makes the picture somewhat metaphysical.

Fear is in the eye of the beholder

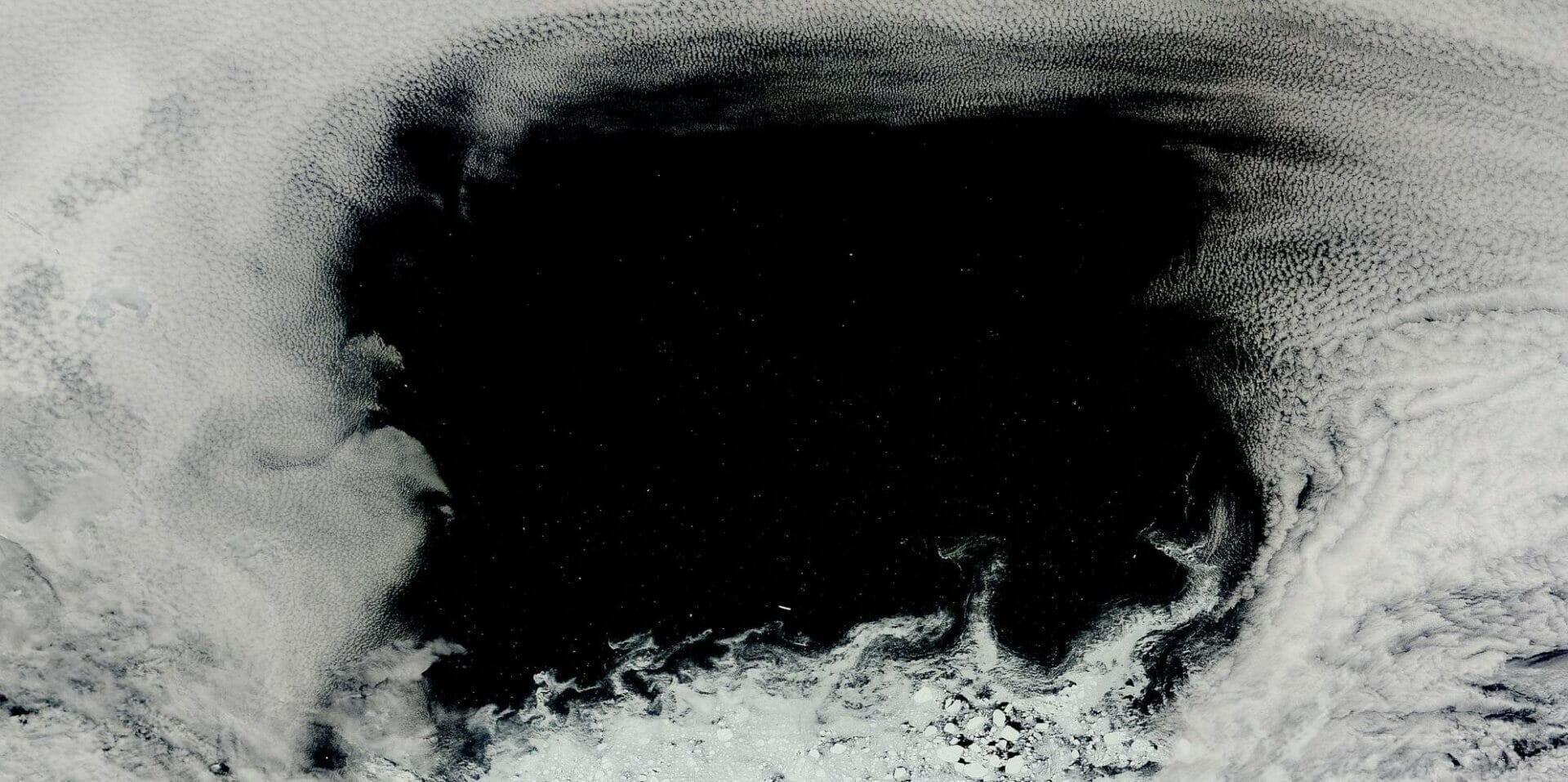

Alien conjures a lethal cocktail of claustrophobia and agoraphobia. Although insignificant compared to space, the starship Nostromo is enormous in size and stifling in its many narrow decks. In this perpetually dark maze, the alien could be hiding anywhere. And the eye of the camera adds to the cabin fever dread.

Low-angle shots with ceilings in full sight abound, leaving no visual room for the viewer’s relief. Transitional shots focus on deserted interiors, making the Nostromo seem like a ghost ship left to wander through galaxies. Star Trek-like images, in which the astronauts look at the stars through the flight deck window, are absent. The universe is not a distance that the crew can simply cross. It is an infinite prison outside and around the already imprisoning starship. Leaving the haunted vessel equals running the risk of getting lost in space.

No true escape from the alien menace is possible. Yet despite this, the alien itself can be seen quite rarely. Just like in Hitchcock‘s Psycho (1960) and Spielberg‘s Jaws (1975), the full figure of the killer is saved for last. Meanwhile, it is up to the viewer to complete what the screen only hints at. The creature shape-shifts in his imagination, maximizing fear. And Terry Rawlings‘ editing doubles down on it, by cutting the alien assault scenes at a berserk rate, with near-subliminal effects.

Alien is a two-way nightmare in which the silver screen acts as a distorting mirror. Scott knew that, ultimately, what could scare the viewer the most was the viewer themselves. The movie would never have reached its worldwide success if all the artists contributing to it – with their disparate backgrounds and expertise – had not kept this in mind. At the end of the day, Alien is the result of teamwork, led by one simple truth. The adage says: “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder”. The same goes for fear.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic