OMORI | All the pain in memories

Game designer

Studio

Art Director

Lead Composer

Publishing Year

Type of game

Genre

Subgenre

Country

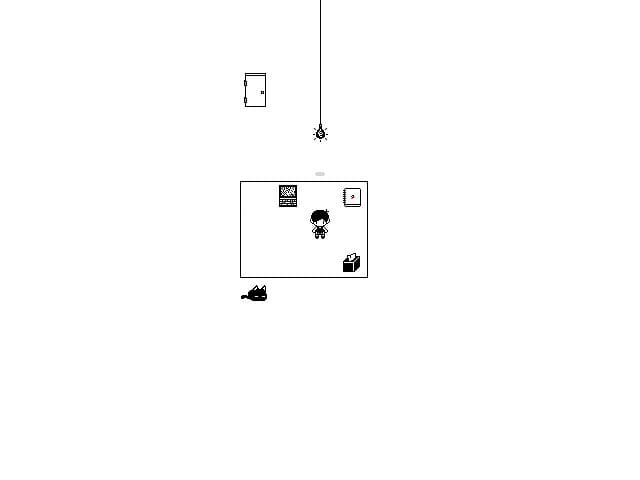

In the first scene of the video game called OMORI a young boy sits in a white room. The room is almost empty, except for a computer, an enigmatic cat, a sketchbook full of disturbing drawings, and a tissue box “to wipe your sorrows away”. A text appears. “Welcome to White Space. You have been living here for as long as you remember.” At that point, a question arises. What about the things you don’t remember?

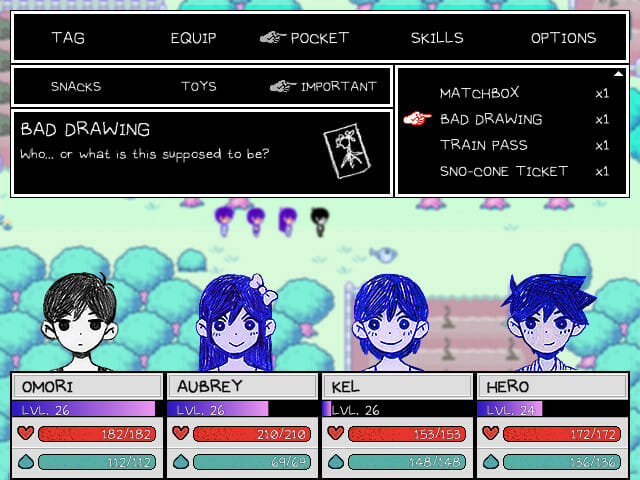

Omori came out in 2020, after almost seven years of development, by a small team led by the artist Omocat. The video game starts off with soft, pastel visuals surrounding the quirky adventures of the leading group of friends, going on a journey to find their lost friend; however, it soon degenerates into a dark discovery of oneself, looking for a truth that is too painful to reveal.

A rocky start: the development of OMORI

The character in stripey shorts and black socks that later became Omori was not born for the video game itself. Omocat had created him – or rather, an earlier version of him – in a webcomic named Omoriboy, which started in late 2011. Omoriboy is a young hikikomori (a condition from which his name is clearly derived) who expresses feelings of loneliness, helplessness, and self-hate. As Omocat started developing a world around this character, they realized that the story kept coming to mind as a video game rather than a graphic novel.

In 2014, Omocat launched a Kickstarter project. At the time, the only ones working on the project were Omocat for the story and art, Pedro Silva (“Slime Girls”) and Jami Carignan (“Space Boyfriend”) for the soundtrack, and ARCHEIA for the game developing part – which would all take place in the program RPG Maker. However, as the project developed the team realized that it was a much heavier burden than imagined. Communications to the backers got more and more scarce as the video game kept being delayed, to the point that many thought the whole project was a scam. Ultimately, Omocat added more people to the team, reaching a total of eight developers and seven game testers. The game finally came out in 2020, putting the doubts to rest: it was a bestseller, and a million copies were sold in 2022.

The fine balance between cute and creepy

One of the most defining characteristics of Omori is its ability to change the mood while staying true to the story, and not coming back on the player. There are two protagonists in the video game: Sunny, a young teenager who has been living in his room for four years, and Omori, his dream persona. There is a strong contrast between the parts of the game that take place in Headspace – the fictional world in which Omori lives – and the real world, in which Omori stops existing and instead Sunny takes his place.

During the first one, pastel hues and cheerful music make the whole experience resemble a child’s dream. In Headspace, Omori and his closest friends will go exploring to look for their lost friend Basil, facing many – cute! – enemies.

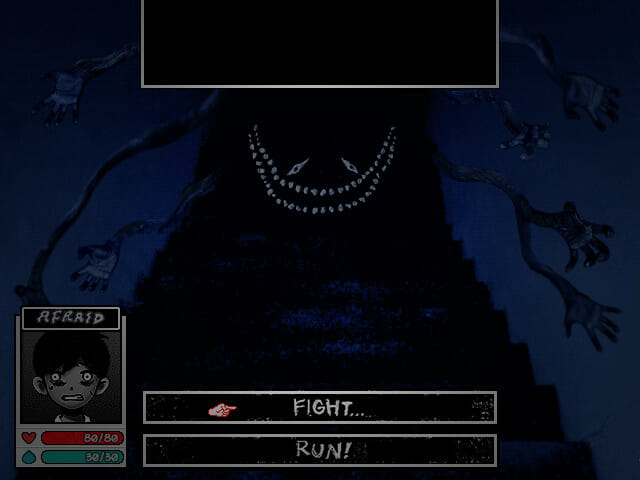

However, when it is time to go home, Omori stabs himself and thus wakes up as Sunny. Sunny’s world is not as cheerful. The colors are dark, the rooms are empty, and monsters fill his thoughts. There are not many jumpscares in Omori. Despite this, its radically changing atmosphere is capable of holding the player on the edge of their seat. Moreover, Omori’s creepiest creature follows him behind his back, as is visible in the mirror. This exploits the human archaic fear of being followed or watched behind our weakest point, our backs.

The game takes place in the USA, but its Japanese influences are clear. After all, the hikikomori culture is most widespread there, as the manga Welcome to the N.H.K. narrates. Two of the most relevant influences video game-wise are Earthbound and Yume Nikki; the first for its RPG structure and the second for its psychological horror elements. Omocat and their team cited many other references. Among them, the Japanese manga Osayumi Punpun shows some similarities in the creative way mental issues are showcased.

Inside the mind of a person in pain

Omori is a second-person perspective video game. This is to say, the player only experiences what the protagonist experiences. If Omori or Sunny do not understand something, the player cannot understand either. This creates a mystery that the player cannot solve on their own: they must rely on Omori or Sunny’s experiences. In Omori, it is clear from the beginning that there is a mystery. Something is hidden from the protagonist. However, many hours will pass before the player gets any clue about what it could be. Most clues are within the Sunny segments, but those are scary and frustrating. Instead, Headspace offers fun challenges and side quests upon side quests. The player is brought to forget about the main quest, which is interestingly also Sunny’s intent in hiding in his room.

But the parallelism between Sunny and the player does not stop there. Many times during the video game, the player is pushed into uncomfortable actions. From stabbing oneself to fighting against phobias to abandoning or fighting friends, uncomfortable moments get more and more frequent. The player has no choice but to get through them if they want to beat the game. Feeling uncomfortable and without ability is close to what Sunny himself feels in the fight against his own brain.

The curse and blessing of memories

Sunny is suspected of suffering from dissociative amnesia. This condition causes a person to block out from their memory certain events that may be traumatic for them. In this condition, blocked memories often come back in the form of dreams or hallucinations. It can be associated with dissociative fugue, in which case the person will create a whole different identity to escape the previous events. Sunny uses Omori’s persona to live in the past before these unknown traumatic events happened.

The game often uses pictures to represent memories. The friends often go through Basil’s photo album, taking the player with them. Photographs have a strong meaning: they can represent regrets or missed memories. They can be hurtful reminders of how much better things used to be. But ultimately, memories are what build a person. Without them, experiences have little meaning. It is up to Sunny (and the player) to turn that nostalgia into something positive. By seeing memories as a constant reminder of the joy he has lived and the love he has received, maybe Sunny will finally be able to accept his past as what it is and move on. To build more memories.

While OMORI has only been out for two years, it has had an effect on the way people look at indie video games. Its popularity has increased exponentially and inspired cosplays, fan art, and fanfiction that expand the story. In an interview with the YouTuber Cydonia, Omocat said that they do not think OMORI will get a sequel, as the story has achieved its purpose. However, they often talk about possible spinoffs that could come in the future.

Tag