The psychological value of failing in Celeste

Game designer

Studio

Art Director

Lead Composer

Publishing Year

Genre

Country

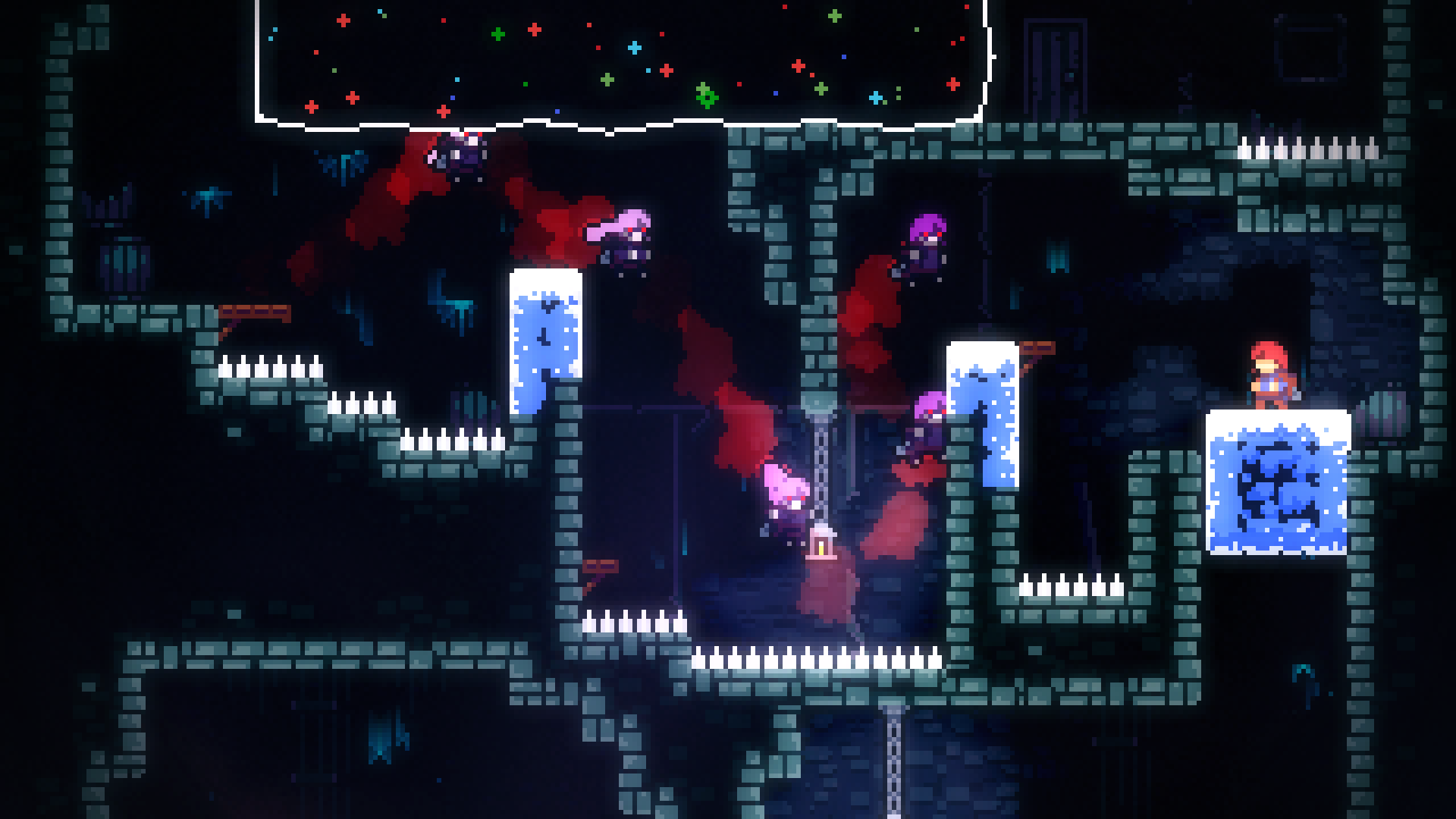

One thing that is common to many video games is the so-called ‘death mechanic.’ The main character dies, either by falling or being killed by something, and the player has to restart the level. Celeste, a 2018 indie video game by Extremely OK Games, took this sometimes stressful mechanic and turned it into a life lesson: to keep going, no matter how hard it is. They achieved this through interesting platforming gameplay, carefully and well thought-out music, and a heartfelt narrative about anxiety.

A mountain made of fractals

The focus of the game is to climb the Celeste Mountain. The protagonist’s name is Madeline, a girl who attempts to escape from her life by challenging the mountain. Through jumps, climbing, and dashing, the player will go through different levels, unlocking new powers as they ascend.

Each area has its unique design, challenges, and plot. According to game designer Maddy Thorson, the game has a fractal structure: it is divided into areas, and every area has different levels. Each level has a story of its own that connects to the main plot. Originally, Celeste was only supposed to be a game about climbing; the plot was implemented when they were already developing chapter 3. The developers then had to go back and change some things up to make everything fit with the new idea.

Despite being a platformer, Celeste‘s map has some elements of metroidvanias, another action subgenre that features big interconnected maps with connections between the level designs and the lore of the game. Similar to these kinds of games – such as Hollow Knight -, Celeste’s areas are all connected to each other.

Gameplay open to all players

Celeste is a challenging game. Especially in the latest parts of it, where jumps require extreme precision to be successful. Despite this, the developers tried to help the player in little ways, making the controls responsive and avoiding unfair mechanics. They wanted the player to feel in control and want to try again. In other words, hard but fair.

Celeste offers an assist mode for players who might want to focus more on the plot, but it also has a hard mode (the “B-side” of cassettes the player finds around) for those who might like a higher challenge. Every level allows different approaches, so each player can find a different solution. The respawn is also immediate and the music does not stop at death. Music actually plays a big part in de-stressing the most difficult parts: Lena Raine wanted the soundtrack to feel peaceful and organic throughout the whole game but expressed Madeline’s anxiety when the situation called for it.

Embracing failure

Almost all mechanics of Celeste point to one theme: failure. The game encourages the player to try again and again, making failure just a part of the journey and not a stop in any way.

Celeste‘s plot largely supports this view as well. As Madeline climbs the mountain, she faces her dark side – literally, a darker version of herself that chases her. It is not simple for her to embrace this side, but the mountain will force Madeline to come to terms with her anxiety – another central theme – and coexist with it, finally reaching the peak of Celeste. Other characters that she encounters along the way suffer from anxiety as well – like Theo, who is overly concerned with how others view him. Celeste’s characters help each other and simultaneously help themselves.

The game is supposed to reflect the developers’ personal experiences with anxiety, and thus no professional was consulted. However, many players have found the game relatable and cathartic. Celeste is not the first media that uses the mountain as a metaphor for an inner journey. Paolo Cognetti‘s The Eight Mountains or Henry David Thoreau’s Walden; or Life in the Woods both involve looking for answers in the wilderness.

Tag