Jeta de santo by Mario Santiago Papasquiaro Review | Contemporary Mexican Beat Poet

Author

Year

Format

Original language

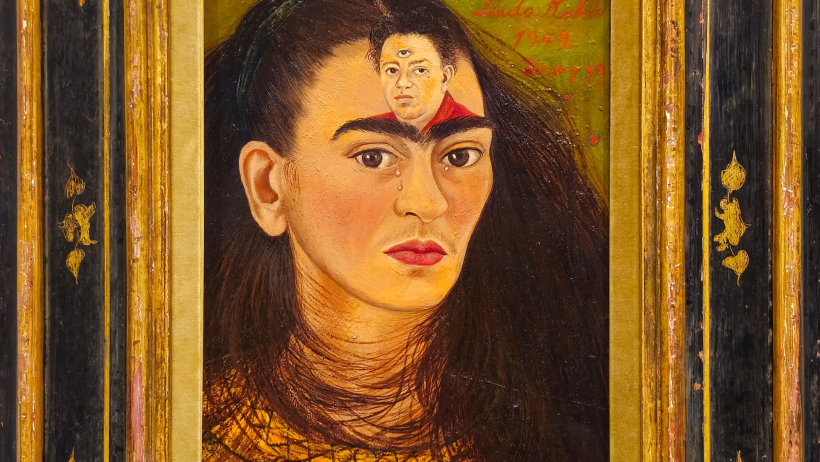

A Philology of Disorder: Jeta de santo (Face of a Saint) is the 2008 anthology that best gathers the poems written by Mario Santiago Papasquiaro between 1974 and 1997. It narrates the life of one of the most striking figures of late 20th-century Latin American literature.

If American culture had discovered Mario Santiago Papasquiaro in the 1980s or 1990s, he would have become a rock icon. His verses would have been quoted in songs, youth films, posters, and scattered across city walls. Here he is the Latin American Neal Cassady, a child of Beat literature and a pioneer of experimental, avant-garde oral poetry.

Born on December 25, 1953, in Mexico City, his birth name is José Alfredo Zendejas Pineda. The American literary scene likely knows him better as Ulises Lima, the nonconformist hero of The Savage Detectives by Roberto Bolaño, the poet’s best friend.

Papasquiaro and the Birth of Infrarealism

The Savage Detectives portrays the personality of Papasquiaro/Ulises Lima. Intolerant of the literary dogmas that dominated the academic circles of the National Autonomous University of Mexico – where he studied – he rejected the “official” Mexican poetry represented by figures like Octavio Paz. Papasquiaro nourished instead a sensibility that clashed with the conservative, rarefied atmosphere of those institutions.

Restless and vital, Papasquiaro met a young Roberto Bolaño at Café La Habana in 1975. After attending poetry workshops at Casa del Lago, the two founded their poetic movement: Infrarealism. They drew on the French Surrealists, Dada, early European avant-garde situationism, and the poetry of Efrain Huerta. Their stories, however, climbed into the remotest corners of Latin America: old dive bars in Distrito Federal frequented by drunken poets overlooking bumpy provincial roads, dreams of revolution, and epic acts of resistance in occupied universities in Mexico and Chile.

A restless, cursed soul

Papasquiaro, however, was an unsettled soul as well. By 1977, he was in Barcelona with Bruno Montané and Bolaño, again under the banner of Infrarealism. From there, he roamed through Paris, stayed at a kibbutz in Jerusalem with Argentine poet Claudia Kerik, and ended up broke in Vienna. His personality was quite complex. Those who knew him didn’t mince words: his brilliance was undeniable, but so was his lack of awareness in many situations. He had a troubled relationship with women, among other issues. Guadalupe Pita Ochoa, one of the founders of Infrarealism and his former lover, describes him this way:

Let’s just say there were many sides to Mario. He showed us a new way of doing poetry—he was a true scholar, and incredibly kind. I discovered the first Beat poets thanks to his translations. He could be very kind, but also incredibly grumpy. Alcohol and drugs made him emotionally unstable, and he could become violent and hard to be around. He had terrible relationships with women throughout his life. While I can’t say he ever assaulted me, I can’t forgive him for the lives he destroyed. I believe we’ll continue to love the wonderful Mario, but we can’t ignore the darker sides of his personality. In many of his poems, he reached excellence effortlessly.

Papasquiaro died in a car accident in Mexico City in 1998. Ten years later the Fondo de Cultura Económica collected his works in the anthology Jeta de santo.

Jeta de santo: The Posthumous Collection

Published in 2008, Jeta de santo gathers the poetic works that Mario Santiago Papasquiaro wrote throughout his life. Divided into five chapters, the most significant poems are Consejos de un discípulo de Marx a un fanático de Heidegger and Canción implacable, which opens with the provocative line: “Me cago en Dios/ & en todos sus muertos.”

A raw, direct, irreverent, and often blasphemous language marks the collection. Whether he’s attacking the Holy Church of Poetry or the Christian God, it’s all the same to Mario Santiago. His texts are driven by frenetic rhythms, often ignoring syntactic and grammatical norms, in the true spirit of Beat poetry.

La poesía sale de mi boca,

de mis puños, de cada poro

resuelto de mi piel /

de éste mi lugar volátil, aleatorio /

testiculariamente ubicado /

afilando su daga / sus irritaciones

su propensión manifiesta a

estallar / & encender la mecha

en 1 clima refrigerador

donde ni FUS ni FAS

ni mechas ni mechones

ni un solo constipado

que merezca llamarse constipado,

ni 1 solo caso de Fiebre-Fiebre

digno de consignarse en este

mi inmóvil país

(From La poesía sale de mi boca, 1974)

The Dadaist and Surrealist influences are evident in his playful and grotesque neologisms, such as the verb “salsaborrachean” (from a Mexican chili and beer sauce) or the superlative “nietzchenísimas” found in Si he de vivir que sea sin timón & el delirio.

Between rock stars and poets

Papasquiaro’s world is populated by human beings engaged in demonic transgressions (like the scene of Mick Jagger singing a duet with Lucifer), and Latin American poets such as the Peruvian Martín Adán and Mexican writer José Revueltas, all caught in a surreal dimension. In Papasquiaro’s wild language, figures from an established academic culture coexist with the psychedelic rock icons of the time, such as the beloved Jim Morrison. His work is also marked by reflective moments, often laced with irony, as he confronts a pain that refuses to conform to traditional emotional tropes:

[…]

—Somos actores de actos infinitos& no precisamente bajo la lengua azul

de los reflectores cinematográficos—

(From Consejos de un discípulo de Marx a un fanático de Heidegger, 1997)

Poetry as sacrifice

For Papasquiaro poetry was a harrowing game of life, a means of distorting precarious, elusive reality while revealing it in its brutal rawness. Thus his poetry is also a way of offering his body to time: naked, distorted by weather, nomadism, hunger, and alcohol. Happily humiliated and sacrificed, with his guts laid bare on the table.

Papasquiaro’s life poem is embodied in his verses. Epic were his encounters, his agnostic pilgrimages, and his nomadic life around Europe. With Papasquiaro Infrarealism – or, as Bolaño called it, “Visceral Realism” – finds its most spontaneous and anarchic expression.

A collection like Jeta de santo could shake up the Spanish-language lyric scene in the contemporary poetic landscape, and open the door to a renewed interest in the underground cultural, social, and political movements that emerged in post-Sixties Latin America under the sign of Infrarealism.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic