Solidity, light, volume | Vincenzo Foppa's style persists over time

Artist

Country

Format

Material/Technique

Dimensions

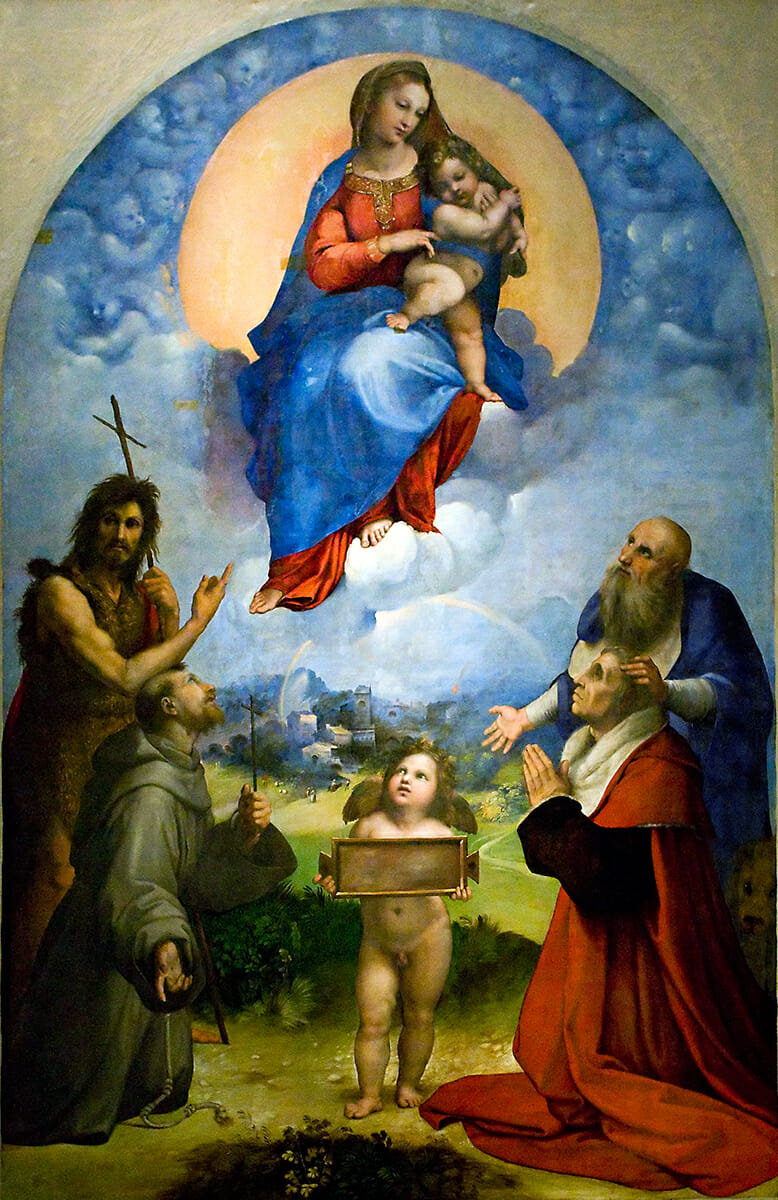

Vincenzo Foppa, the first artist and leader of the Lombard School (the group of artists that worked in the area of the Duchy of Milan), painted around 1480 this Madonna and Child. This painting, probably conceived for private devotion, exemplifies and summarises Foppa’s style, marked by its solidity, light and volume.

Foppa’s style: solidity, light, volume

Vincenzo was born in Brescia around 1430 and was one of the most important painters active in Lombardy before Leonardo da Vinci‘s arrival in Milan in 1482. He trained in a courtly entourage that was still anchored to International Gothic, yet he managed to pioneer in a new style. He set the bases of a new way of painting that many other artists, such as Ambrogio da Fossano, also called Bergognone, would learn to use in the following decades.

The solidity and the volume of the bodies, the dour appearance of the flesh (as one can see in this Madonna), and particular attention to how the light hits the figures characterize Foppa’s style.

Foppa’s success: respect for tradition, innovative painting

One of the remarkable qualities of his art is that he was able to innovate while respecting canonical dictations. The Madonna and Child is one of the most common topics of the whole history of art, as private and public institutions often commissioned it. Yet Foppa, while even having to follow a very concrete structure and theme, created something new. This might be one of the reasons for his success: a canonical structure but an innovative way of painting. One can observe this in some important commissions such as the Pala Bottigella (1480-1484) or the Pala della Mercanzia (end of the 15th century), restored in 2017.

Foppa’s most famous work is the Portinari Chapel in Milan (1462-1468), influenced by Tuscan architecture but painted in the realistic and solid new Lombard style.

Magister fecit: Bergognone follows Foppa

Bergognone, one generation younger than Vincenzo, grasped and poured into altarpieces and panels all of Foppa’s innovations. A clear comparison can be made between Foppa’s Madonna and Child (or the madonnas from the aforementioned altarpieces) and one of Bergognone’s works (of the same topic) from the National Gallery, London.

There is the same grey color to give tridimensionality to the figure, the same porcelain aspect of the skin, the same volume, the same light.

Foppa’s style, solidity and volume in aeternum

Foppa’s innovations went on to be the main characteristic of Lombard art for years and years. The darkness that he gave to his paintings, the lights, and the shadows are a leitmotiv of Milanese artists. These characteristics marked the end of the Quattrocento, the entire Cinquecento, of the 17th and 18th centuries in Northern Italy. Even Caravaggio was deeply impressed by the Lombard use of light, that he later adopted and developed.

Some post-Avant-garde paintings also show these typical Lombard features. The historiographical term “ritorno all’ordine”, which can be translated as “return to order” is used to describe the style of the Novecento Group, founded in 1922 and theorized by Margherita Sarfatti. Some of the members were Mario Sironi, Achille Funi or Pietro Marussig. Their art can be linked to Foppa’s style: grey shadows, dark paintings, and solid volumes. Some paintings by Sironi show it clearly, such as some portraits by Funi or Marussig.

Arturo Martini translated into sculpture what others had done on canvas or wood. The faces he created in terracotta are the same ones Foppa had painted five centuries before. This Maternity is one of the most explicit examples of the transposition of Vincenzo’s style into tridimensionality:

Foppa’s innovations, despite being in demand from collectors and affected by frequent commissions, have remained and persisted over time. Light and shadow, volume and solidity have been for over five hundred years the most distinguishing characteristics of Lombard Art.

Tag