V for Vendetta Comic Review and Analysis | The power of masks and symbols

Year

Format

By

Remember, remember, the fifth of November, gunpowder, treason and plot.

V for Vendetta, written by Alan Moore and illustrated by David Lloyd, is a miniseries born in the pages of Warrior, a cutting-edge British magazine in the 1980s comics world. After the magazine closed in 1985, DC Comics republished the chapters already released, adapting them from black and white to color and concluding the story.

V for Vendetta stands out for its incisive criticism of propaganda and totalitarianism, overturning the conventions of American comics, often associated with the American Dream and nationalist rhetoric. Furthermore, as Moore usually does by deconstructing the very principles of comics, through V he reworks the traditional principles of superheroes, distancing himself from a dualistic vision of good and evil. On the contrary, V’s actions are driven by contradictory and personal motivations, posing questions about the idea of freedom and justice.

Norsefire

In V for Vendetta, the government of a futuristic England is the Norsefire, a fascist regime that has eradicated all forms of dissent. Through widespread control, Norsefire has eliminated all ethnic, sexual and political minorities, relegating anyone who does not conform to its standards to concentration camps. The population lives in terror, while the power is based on a rigidly organized structure: The Eye and The Ear monitor citizens, The Mouth spreads propaganda, and The Fingers are the police force responsible for maintaining order.

In this context, V emerges, an enigmatic masked rebel who opposes the system. After surviving experiments in the Larkhill concentration camp, V wants to overthrow the Norsefire regime and awaken the conscience of the citizens. With his face hidden by a Guy Fawkes mask, V launches himself into a series of acts of sabotage and attacks against the regime’s institutions, such as the destruction of Parliament and the elimination of key figures in power.

During his mission, V saves Evey Hammond from the Fingermen and introduces her to his struggle, making her understand the need to take action against oppression.

Beyond Heroes

Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta analyzes freedom and resistance against oppression through a dystopian lens, reminiscent of Orwell’s themes. The political climate of 1980s England under Margaret Thatcher‘s conservative government influenced Moore’s depiction of a strictly controlled society, symbolizing the oppressive tendencies he perceived in Thatcher’s government.

However, the anarchy proposed by V is not only a destructive force, but also a creative one: it offers the possibility of a new social construction based on freedom, without the intervention of a central authority.

Moore, despite the fight against totalitarianism, doesn’t present V as a hero, since he’s guilty of wanting to take justice into his own hands. This approach is linked to Moore’s subsequent work in Watchmen, where he continues his critique of the superhero genre, deconstructing its canons and highlighting the more human and problematic side of his protagonists; in both works, Moore emphasizes the ambiguous boundaries between justice and revenge.

How legitimate is it to resort to violence to obtain freedom? Moore’s moral position is deliberately elusive: he neither condemns nor fully approves of V’s actions, leaving the audience to reflect on the ethical implications of such choices, but suggesting that perhaps, sometimes and when the context requires it, taking justice into one’s own hands could be the only solution.

In Watchmen, Moore continues this reflection by moving further away from siding with one faction or the other: characters like Rorschach embody the concept of private justice, but their actions often show how dangerous are those who place themselves above the law.

David Lloyd, with his illustrations, enriches the novel with an innovative and minimalist graphic approach. His artistic choices eliminate captions and onomatopoeia, allowing dialogues and images to tell the story in an essential way. This amplifies the tension, making every silence and every visual expression full of meaning (while V’s face remains always unpenetrable, as he wears a mask the whole time).

The color choice, curated by Steve Whitaker, adopts dark tones and delicate nuances, evoking a gothic atmosphere that ties in with the desolation of the totalitarian regime represented. Even in the color version, the tones remain muted, helping to keep intact the gloom and emotional intensity of the story.

V’s Dualism

The character of V in V for Vendetta represents a moral and political enigma. He is neither a conventional hero nor a simple antagonist. His mission is clear: to destroy the corrupt power to restore freedom to the people. However, his methods – violent and radical – raise questions about the legitimacy of his actions and the boundary between justice and terrorism. His acts of violence, including murders and attacks on symbols of power such as the Old Bailey and the Palace of Westminster, place him in a moral grey area. V does not act for personal revenge – even if conceptually he could have the right to do so – but for an idea: freedom. He justifies the use of force, arguing that only through the destruction of the system is it possible to create a new order and a new freedom.

The complexity of the character is also reflected in the contrast between V and the other protagonists, such as Inspector Finch and Evey. Finch embodies the search for truth within the system, while Evey is the figure who gradually evolves, going from victim of the regime to disciple of V’s anarchist thought. Together, these three characters offer the reader different points of view on justice, resistance and power.

If therefore totalitarianism is intrinsically wrong, does this mean that anarchy is the way to follow?

Actually, anarchy is not an easy or cost-free solution either. V’s anarchy requires the total destruction of the established order, and Moore does not hide the dramatic consequences and human price of such a revolution. Both political visions therefore offer lessons on the risks of absolute control and the importance of free will.

Democracy could be a third available option, but V for Vendetta never explicitly mentions it. Rather, it is left to the subtext. Moore, through the character of V, seems to suggest that democracy, if not supervised, could easily degenerate into an authoritarian government like Norsefire.

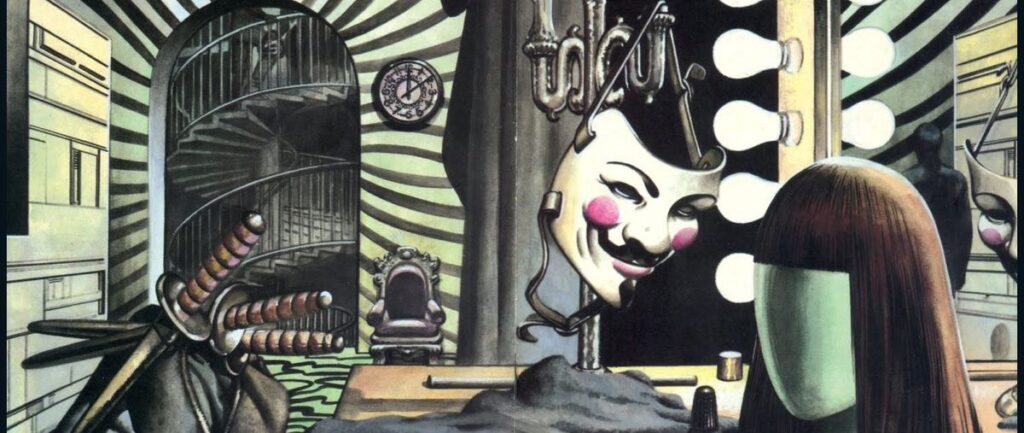

The Power of the Mask

The mask has often represented much more than a simple disguise: it allows characters to transform themselves, explore their double, or hide their intentions. In works such as Pirandello‘s The Late Mattia Pascal, the mask is a metaphor for a fluid identity, with the protagonist reinventing himself to escape social norms; in The Phantom of the Opera, the mask becomes a symbol of pain, mystery and self-isolation. In both works, the mask is a way to face the world from outside social conventions. Similarly, the Guy Fawkes mask in V for Vendetta has taken on a cultural relevance that goes beyond the comic. The wearer is not a single individual, but part of a larger idea, as if personal identity were sacrificed in the name of a universal principle.

Guy Fawkes, the historical figure to whom the mask refers, was one of the conspirators of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, a failed attempt to blow up the English Parliament to overthrow the Protestant government. Even though the plot failed, Fawkes became a symbol, an image that Moore and Lloyd reinvented for their protagonist.

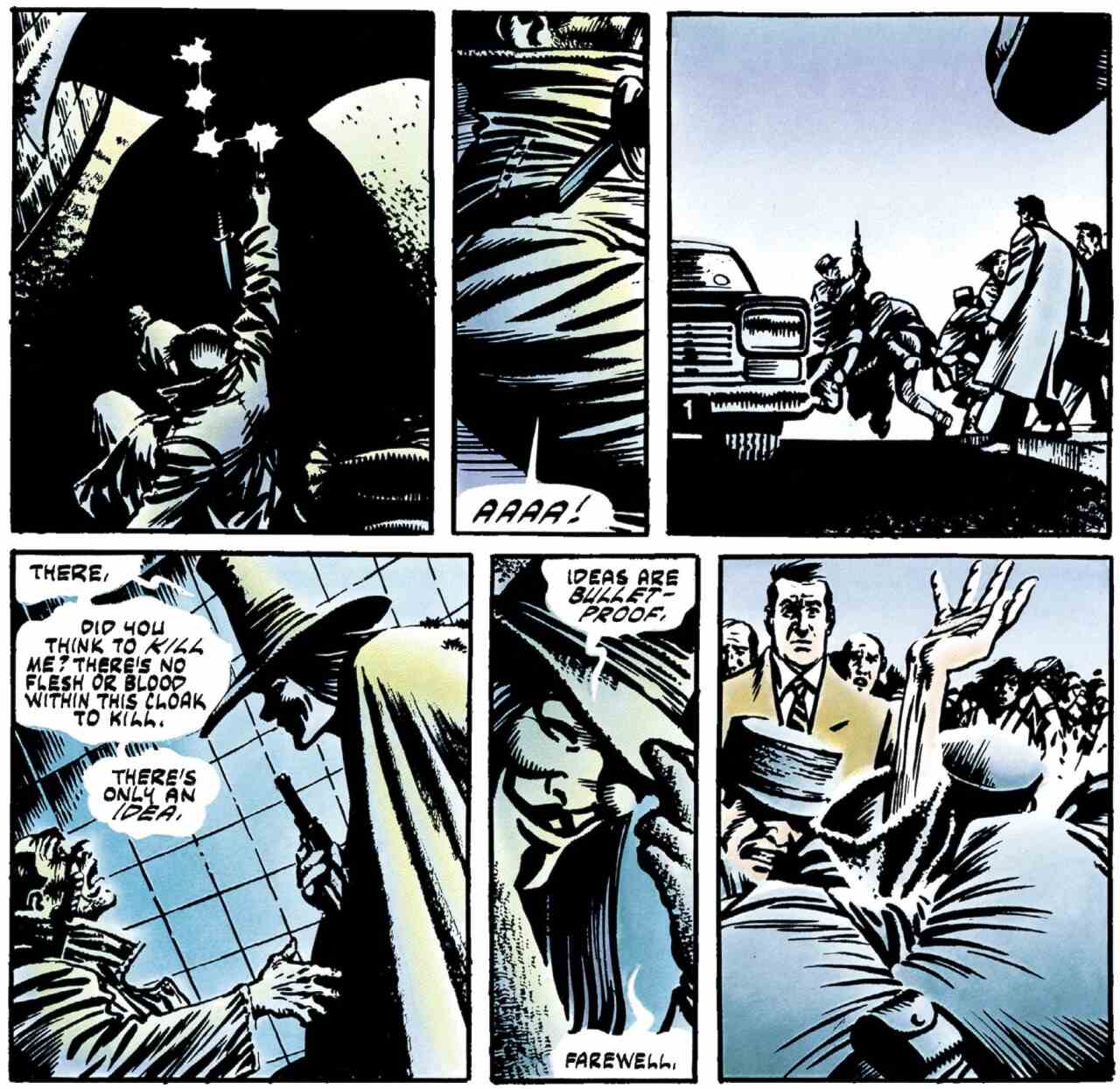

In the comic, V becomes himself a symbol of anarchy and resistance. His identity is deliberately undefined, because what matters is the message he embodies. V is not just a man seeking revenge, but an idea that transcends the individual. As he states in his final speech, “Ideas are bulletproof”, underlining how people can die, but ideals continue to live and thrive.

His final speech is one of the most famous moments of V for Vendetta, both in the comic and in the 2005 movie. In the comic, V says: “People should not fear their government. Governments should fear the people.” The speech in the movie, however, has a different emphasis: while maintaining the idea of resistance against oppression, it emphasizes unity and mass action, transforming the speech into a direct call to arms: “I invite you to look at the face of the culprit responsible for this situation… you will see it every time you look in the mirror.”

This difference between the two media underscores a central point: V, more than a simple character, is a symbol that takes on different nuances depending on the context. The comic focuses on the philosophy of freedom, while the film embodies a more direct and concrete vision of rebellion. Both versions, however, share the same basic idea: the fight for freedom requires not only the courage to act, but also the ability to think and reflect on what it really means to live in a just society.

Betrayals

At the beginning of the story, Evey is a fragile and defenseless figure, but, under the guidance of V, she undergoes a change that reflects the transformative potential of anyone who manages to see beyond the propaganda.

Evey therefore represents the entire world population. Through her experiences of imprisonment and liberation, Moore shows us that anyone can be reborn. This concept ties in with the way the V mask has found an autonomous life in reality, being adopted by movements such as Anonymous, Occupy Wall Street or the Indignados in Spain, and used during global protests. The original meaning of the mask, however, has been emptied over time, becoming more of a universal symbol of dissent, often without a direct connection to the anarchist and philosophical themes that Moore had outlined.

However, the scene in which Evey discovers that she has been imprisoned by V is once again a reflection of how, from the comic to the movie and then to reality, the original meaning of V for Vendetta has unfortunately been lost.

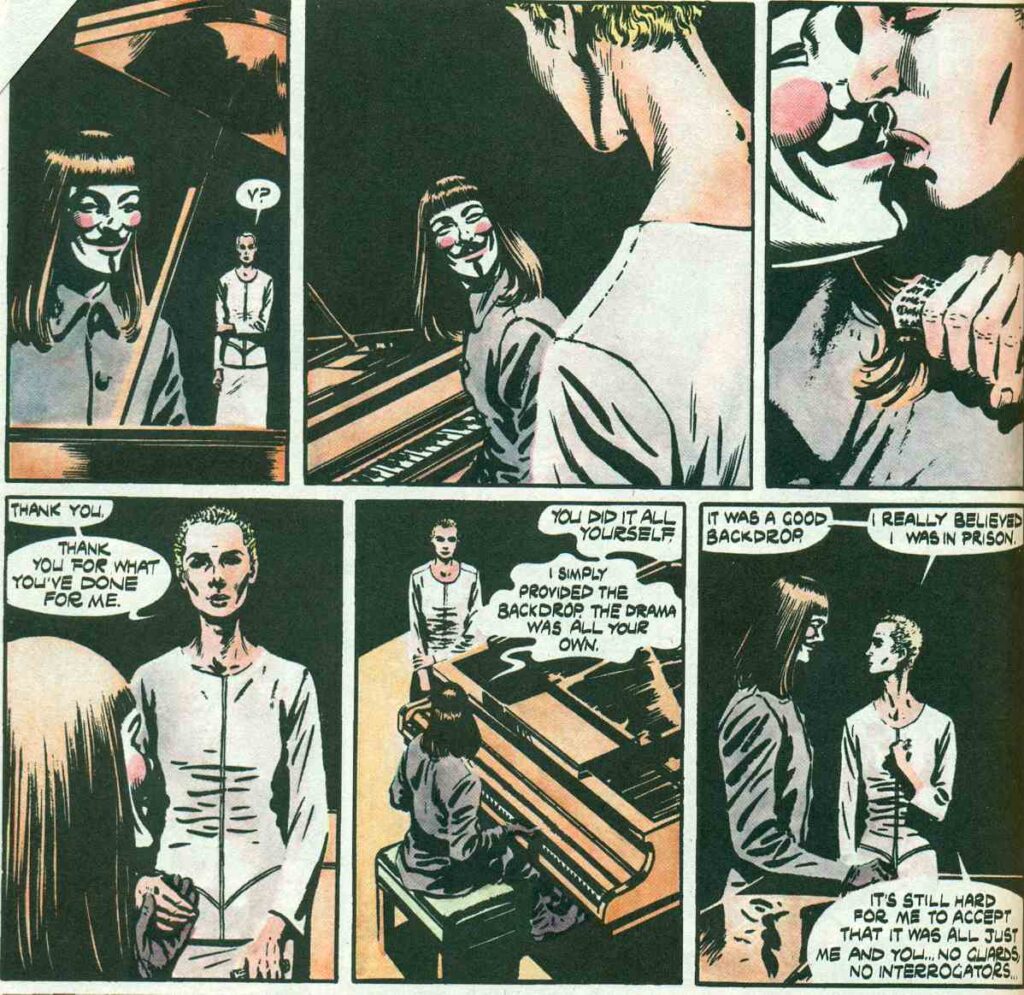

In the comic, Alan Moore emphasizes that someone cannot be truly free until they are a slave to fear. V uses imprisonment to force Evey to confront her deepest fears and accept the idea that absolute freedom can only exist if she is willing to give up her life. After believing that she is in a real prison camp, indeed, Evey comes to the conclusion that she prefers death rather than submitting to the regime.

In the movie, the focus shifts. V’s actions are not a philosophical demonstration, but a means to awaken Evey and make her embrace the revolution.

From Anarchy to Pop Culture

Today, Alan Moore has a critical relationship with V for Vendetta: he wrote it to explore philosophical themes, but later it became a generic, pop symbol of rebellion, often in contexts far from the author’s original vision. For Moore it is therefore further proof of modern society’s tendency to empty meaningful messages to adapt them to superficial and commercial ones.

It’s been a decade since I disowned V for Vendetta. Regarding the mask and its mysterious spread as an icon of protest from Tottenham Court Road to Beijing, while I have always been happy that my work can support global protest movements, I do not give indiscriminate support to anyone wearing a piece of Warner Bros. merchandise.

Alan Moore to the Italian newspaper Il Corriere della Sera

Despite everything, however, V for Vendetta continues to present itself as an extremely relevant work, which challenges the reader to reconsider the limits of power and what to be really free actually means.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic