Since the beginning of storytelling, allegories have been used in narratives to convey morals and teachings. From folk legends to sacred scriptures, fairy tales, and even movies. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the children’s novel by the famous English author Roald Dahl, is one of these allegorical stories. The deadly sins (or capital vices) find a symbolic interpretation both in the original work – made eternal by the character of Willy Wonka – and in its various adaptations. A truly modern iconography that allows for a multi-layered reading, staging a child-friendly Dantean hell.

- Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is inspired by real events

- The plot: five children blessed with good fortune

- Modern fairy tales and ancestral systems

- It’s great to be kids

- The iconography of the Deadly Sins in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

- Gluttony / Augustus Gloop

- Lust / Veruca Salt

- Pride / Violetta Beauregarde

- Wrath / Mike Teavee

- Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

- The origins of Burton’s adaptation

- Novel vs. Movie

- Burton’s technique and style

- The movie version of The Hells

- Big punishments for little sinners

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is inspired by real events

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory was first published in 1964 by Alfred A. Knopf in the US and George Allen & Unwin in the UK. The author was inspired by some real events. For example, the habit of Cadbury’s, one of the most famous confectionery manufacturers in the UK, to send free samples to university students in advance, and then start mass production of only those sweets that received the best grades. In addition, an actual war between candy manufacturers began in the twenties. The novel tells of real-life spies sent to steal secret recipes from competitors.

The sequel to the novel, Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator, was published in 1972. Although Dahl originally intended to write a trilogy, the third volume remained unfinished. American director Mel Stuart made the first movie adaptation in 1971, Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, starring Gene Wilder. In 2007, Tim Burton engaged the versatile Johnny Depp to play the eccentric chocolate maker in his movie of the same name. In December 2023, Wonka was released in cinemas, a prequel directed by Paul King and dedicated to the chocolate factory’s founder and owner, played by Timothée Chalamet.

The plot: five children blessed with good fortune

Charlie Bucket is a boy born into a family so poor that his four grandparents share the only bed. His father works in a toothpaste factory, and his mother can only cook cabbage soup. Only once a year, on his birthday, does Charlie get a chocolate bar, which he loves. The day before Charlie’s birthday, Willy Wonka, the owner of the mysterious chocolate factory that has been operating without workers for many years, announces a contest. He has hidden five golden tickets in the packages of his famous chocolate bars. The five children who find them will visit his factory and receive a lifetime supply of confectionery.

August Gloop, a chubby, sweet-toothed kid, soon finds the first ticket. Veruca Salt, a spoiled young girl allergic to the answer “no”, gets the second. Violetta Beauregarde, a champion who can’t lose a contest, wins the third, even though she doesn’t like chocolate. Mike Teavee, a child addicted to television, wins the fourth ticket by solving an algorithm. When he receives his bar, Charlie unwraps it with trembling hands but finds only chocolate. A few days later, luck is on his side and he finds some money outside a sweet shop. So he becomes the fifth lucky child to visit Wonka’s Chocolate Factory.

Modern fairy tales and ancestral systems

The first edition of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory also included original drawings by the author to support and complete the descriptions. The illustrations show the characters exactly as Roald Dahl imagined them. They also create a link between the novel and classic children’s books. In addition, Dahl’s narrator speaks directly to the reader, creating a dialogue reminiscent of oral storytelling.

The characters also share some similarities with folk and historical stories. The Oompa-Loompas are small creatures from a distant and mysterious world. They recall the singing, hardworking dwarves of Snow White. Even the squirrels, trained to peel nuts, recall the anthropomorphic animals that appear in many fairy tales, such as Cinderella‘s mice. The factory itself, a gluttonous dream of candy, is halfway between Pinocchio‘s Pleasure Island and a giant version of Hansel and Gretel‘s candy house. Moreover, the children’s appearance seems to give a tangible form to their personalities, expressing their weaknesses.

It’s great to be kids

Augustus, Veruca, Violetta, and Mike embody a capital vice that will cause them to pay the consequences of their actions. Charlie, on the other hand, becomes a symbol of childlike purity. Many of Dahl’s works – including James and the Giant Peach (1961) and Matilda (1988) – deal with the moral superiority of children. Adults, on the other hand, are often portrayed as insensitive and silly, too attached to the material world to get to the heart of reality. This is also a recurring theme in The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, although Charlie is more like Oliver Twist and other Dickens characters, as extreme poverty shapes his personality. Wonka himself owes his incomparable genius to the fact that he never really grew up, and so he retained a deep connection to the childlike ability to dream.

So children find themselves as modern-day Davids dealing with Goliath. The latter, in addition to being older, have the power to make decisions. But that doesn’t mean the end is preordained. As in the best legends, Dahl teaches us that heroes can take on any dimension. Rather, cunning and a noble spirit are their weapons, allowing them to win even when it seems impossible.

Willy Wonka, eclectic and crazy, becomes a guide in a heaven that sometimes turns into hell for those who break the rules. Just as classic fairy tales hide a moral, the narrator’s voice instinctively clarifies a lesson, never exaggerating or becoming a know-it-all. Augustus, Veruca, Violetta, and Mike give concrete form to sins that deserve punishment. In this way, Dahl’s story becomes a modern allegory that makes vices real and creates a new iconography.

The iconography of the Deadly Sins in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

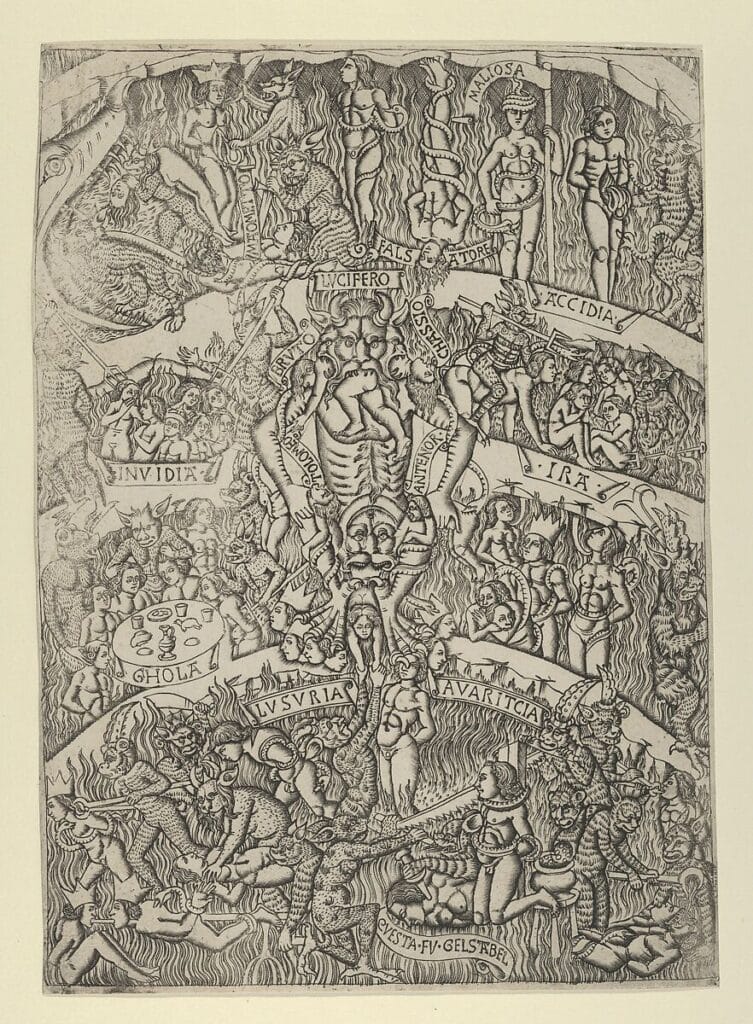

In Christianity, the seven deadly sins are a category of immoral behavior. Although they aren’t directly mentioned in the Bible, there are some analogies to the seven acts that God abhors in the Book of Proverbs. The behaviors in this category can lead to other sins. Pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust, gluttony, and sloth are the seven capital vices. These evils are often opposed to virtues, especially the three theological virtues and the four cardinal virtues.

The word “vice” comes from the Latin “vĭtĭum,” which means lack or deviant habit. Because these vices are worse and crucial to human nature, they are considered “capital”. Their categorization began with the Desert Fathers, especially Evagrio Pontico. Later, his disciple Giovanni Cassiano spread it throughout Europe, thanks to the book The Cenobitic Institutions. This categorization deeply influenced Catholic confessional practice, as well as literary works such as Dante‘s Purgatorio. Various works of art in Catholic churches and ancient volumes depict the seven deadly sins. In the Western Christian tradition, these sins were considered to be terrible deeds, on a par with those against the Holy Spirit and those praying for heavenly vengeance.

Gluttony / Augustus Gloop

The very next day, the first Golden Ticket was found. The finder was a boy called Augustus Gloop, and Mr. Bucket’s evening newspaper carried a large picture of him on the front page. The picture showed a nine-year-old boy who was so enormously fat he looked as though he had been blown up with a powerful pump. Great flabby folds of fat bulged out from every part of his body, and his face was like a monstrous ball of dough with two small greedy curranty eyes peering out upon the world. The town in which Augustus Gloop lived, the newspaper said, had gone wild with excitement over their hero.

Roald Dahl, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964)

This is how the author portrays Augustus Gloop, the first winner of Willy Wonka’s Golden Ticket. Like Dahl, artists from past centuries, from Giotto to Jacques Callot, from Hieronymus Bosch to Otto Dix, have interpreted the capital vices, each with their iconography.

The sin of gluttony is considered one of the deadly sins. It is opposed to the virtue of modesty and is associated with social injustice, especially in the Middle Ages, when poor people couldn’t buy food. Each sin has its symbolic iconography. Gluttony is identified with the possibility of visibly changing the body, making it fat and deformed. Sometimes these subjects were depicted with their necks stretched out, or together with animals traditionally associated with greed, such as bears, wolves, or pigs.

In Dante’s context, gluttons are represented as a shapeless mass, covered with dark mud, without joy or hunger. Dante and Virgilio walk carelessly on this infernal slime. It symbolizes the loss of the gluttons’ joyful hunger, now reduced to stinking souls submerged in a sea of dark mud.

Lust / Veruca Salt

The newspapers announced that the second Golden Ticket had been found. The lucky person was a small girl called Veruca Salt who lived with her rich parents in a great city far away. Once again Mr. Bucket’s evening newspaper carried a big picture of the finder. She was sitting between her beaming father and mother in the living room of their house, waving the Golden Ticket above her head, and grinning from ear to ear.

Roald Dahl, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964)

Lust is the sin associated with Veruca Salt, the second winner of Wonka’s Golden Ticket. An extreme attachment to material goods is the manifestation of this vice, which was considered particularly serious in the Middle Ages. Carnal sins, such as those committed by Paolo and Francesca, are also equated with lust. During the Renaissance, the gravity of this sin diminished, allowing men to satisfy their desires. As a result, lust can be represented as a female figure, ugly and naked, afflicted by snakes, or beautiful as Venus, the seductive goddess of love. Animals such as rabbits, crocodiles, billy goats, and partridges often represent lust.

Dante’s contrapasso for lascivious sinners is represented in the second circle of Hell. They are pursued by an infernal wind, a representation of the uncontrolled desire that led them to sin during their life on earth. This tempestuous wind relentlessly pushes lascivious souls back and forth, never finding peace. They are doomed to wander forever in this blizzard, symbolizing the lack of control and stability that characterized their behavior in life.

Pride / Violetta Beauregarde

The third ticket was found by a Miss Violet Beauregarde. There was great excitement in the Beauregarde household when our reporter arrived to interview the lucky young lady. […] And the famous girl was standing on a chair in the living room waving the Golden Ticket madly at arm’s length as though she were flagging a taxi. She was talking very fast and very loudly to everyone, but it was not easy to hear all that she said because she was chewing so ferociously upon a piece of gum at the same time

Roald Dahl, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964)

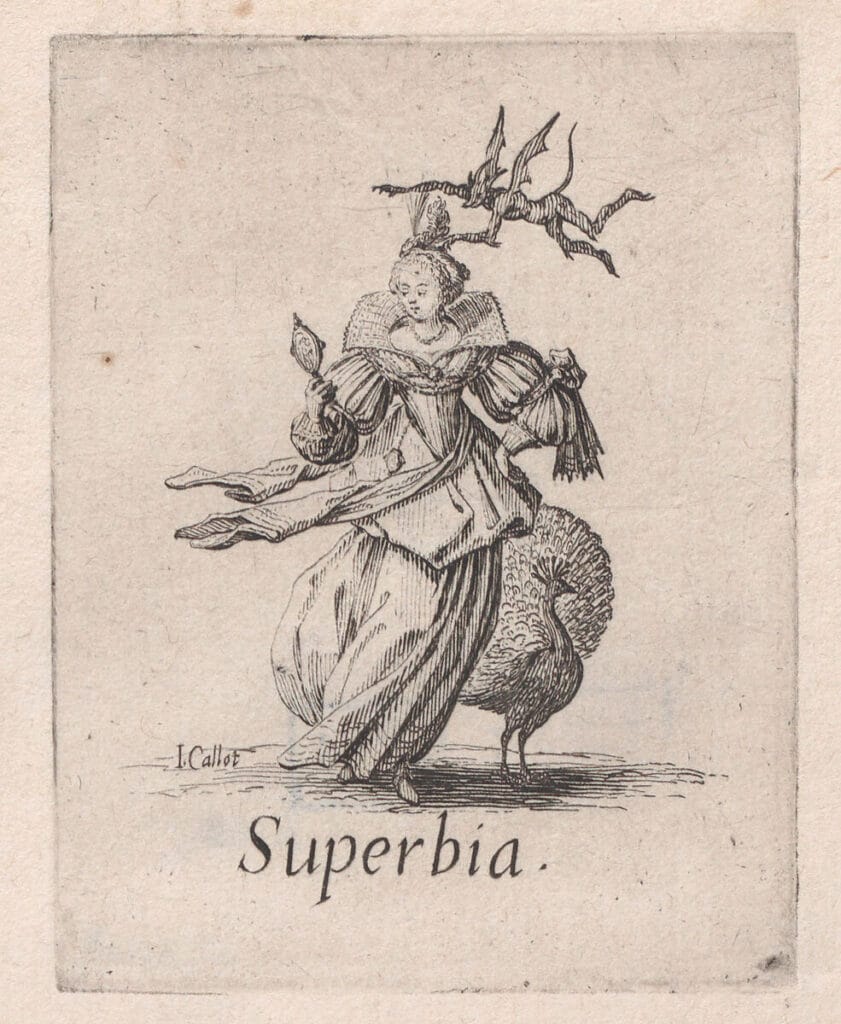

The character of Violetta is associated with the sin of pride. It’s a capital vice associated with considering oneself superior to everything, even laws. It is often depicted as a woman dressed in red admiring herself in a mirror. Sometimes she’s in the company of a lion, a bat, an eagle, or a peacock. Often the mirror reflects Satan.

Purgatory is the contrapasso for those whose sin was pride in the Divine Comedy. Huge rocks, representing their arrogance, force the sinners to keep their heads down, crushed under their weight. Consequently, Dante’s contrapasso for this vice is the complete reversal of this behavior through humiliation.

Wrath / Mike Teavee

«The Taevee household» said Mr Bucket, going on with his reading, «was crammed, like all the others, with excited visitors when our reporter arrived, but young Mike Taevee, the lucky winner, seemed extremely annoyed by the whole business. “Can’t you fools see I’m watching television?” he said angrily. “I wish you wouldn’t interrupt!”…»

Roald Dahl, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964)

Because loss of control and a vengeful expression are common in this stage of life, when self-consciousness hasn’t fully developed, anger is often associated with young characters like Mike Teavee. The youth is often depicted with fiery eyes and armed with a sword or dagger.

The fifth circle of hell in Dante’s Divine Comedy depicts the contrapasso for those whose sin is wrath. There, irascible souls bet against each other in a muddy river called the Styx. Consequently, according to Dante’s vision, the contrapasso for those who have sinned of wrath involves a punishment by which sinners remain trapped in a place that reflects the destructive and tumultuous nature of their anger.

Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

The four children also approach and respect this iconography in the movie adaptations of Dahl’s novel. Especially in the 2005 Tim Burton movie.

Augustus Gloop (Philip Wiegratz) is true to the author’s description. The child nearly drowns in a giant river of chocolate, reminiscent of the dark mud that covers the gluttons in Dante’s hell. Veruca Salt (Julia Winter), the spoiled girl allergic to the word “no”, remains the victim of an attack by the working squirrels who take her away. Violetta Beauregarde (AnnaSophia Robb), the award-winning record champion who considers herself superior to her peers, finally suffers the humiliation of swelling up and becoming a giant rolling blueberry. Finally, Mike Teavee (Jordan Fry) remains an irascible, know-it-all, TV- and video-game-obsessed boy who is eventually minimized by Wonka’s “Television Chocolate”.

The origins of Burton’s adaptation

Roald Dahl was less than enthusiastic about Mel Stuart’s first movie version, starring Gene Wilder. His screenplay had been discarded and later rewritten by David Seltzer, who added excessive changes to the original plot and melodies that the author found too sappy. After his death, Warner Bros. searched for a long time for the ideal director for a new adaptation. Finally, in agreement with Felicity Dahl and her daughter Lucy, they chose Tim Burton. Burton was a big fan of Dahl’s work and had already produced an adaptation of one of his novels, the 1996 animated movie James and the Giant Peach. In addition, Burton did not like Stuart’s adaptation, which he felt was too far removed from the original work.

Burton was able to read the original manuscripts when he visited the author’s home. The director was particularly fascinated by the dark humor of some private versions of the original texts, which were later published only with several cuts for the parts considered “politically incorrect”. Working together with screenwriter John August, they had only one goal: to remain faithful to the novel to make the movie “as Roald Dahl-y as possible”.

To create the soundtrack, Burton asked his longtime collaborator Danny Elfman to join the project. Johnny Depp portrays Willy Wonka, and a young Freddie Highmore plays Charlie Bucket.

Novel vs. Movie

Burton’s adaptation is more respectful of the original work. The artistic duo Burton/August includes several parts of the book that were cut from the 1971 movie, such as the construction of the giant chocolate palace for the Indian prince and the squirrels’ attack on Veruca. However, the movie also includes other new elements, such as the father-son relationship and the importance of family, as well as the story of Wonka’s origins.

On more than one occasion, Burton has explored the delicate relationship between parents and children, a theme he has investigated since his debut with the short movie Vincent. In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the director uses many flashbacks to recreate the conflict between Willy Wonka and his father, Dr. Wilbur Wonka (Christopher Lee). These flashbacks show Wonka’s childhood, misunderstood and unhappy, with a too-inflexible father, allowing the public to explore different sides of such an iconic character.

Depp’s Wonka, the actor admitted, was to be completely different from Wilder’s version. Depp and Burton’s mad chocolatier was inspired by oddball characters from children’s television, such as Bob Keeshan from Captain Kangaroo and Al Lewis from The Uncle Al Show. And for Wonka’s hair and glasses, Depp turned to Vogue America director Anna Wintour.

Burton’s technique and style

Burton’s trademark elements are present in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The director’s signature gothic aesthetic, with its dark tones, is evident in the extremely curved and sharp-edged Bucket house (a homage to the cabin where Dahl used to write), as well as in the family’s faces and wardrobe. All the family members are excessively thin, due to the poverty in which they live, and feature the classic hollowed-out faces of the director’s most famous characters (such as the unforgettable Emily in Corpse Bride).

The high-key lighting technique was used extensively for the scenes inside the factory to make them brighter and to highlight the brilliant and vivid colors, such as the red of Wonka’s coat or the green of the fake chocolate grass, creating an extraordinary atmosphere. In addition, the high-key lighting emphasizes the contrast with the boring real world outside Wonka’s factory.

The movie version of The Hells

The first adaptation was already considered a children’s horror movie because of some frightening aspects of some scenes. Even in the movies, the adventure in the chocolate factory resembles a trip to Dante’s hell suitable for children.

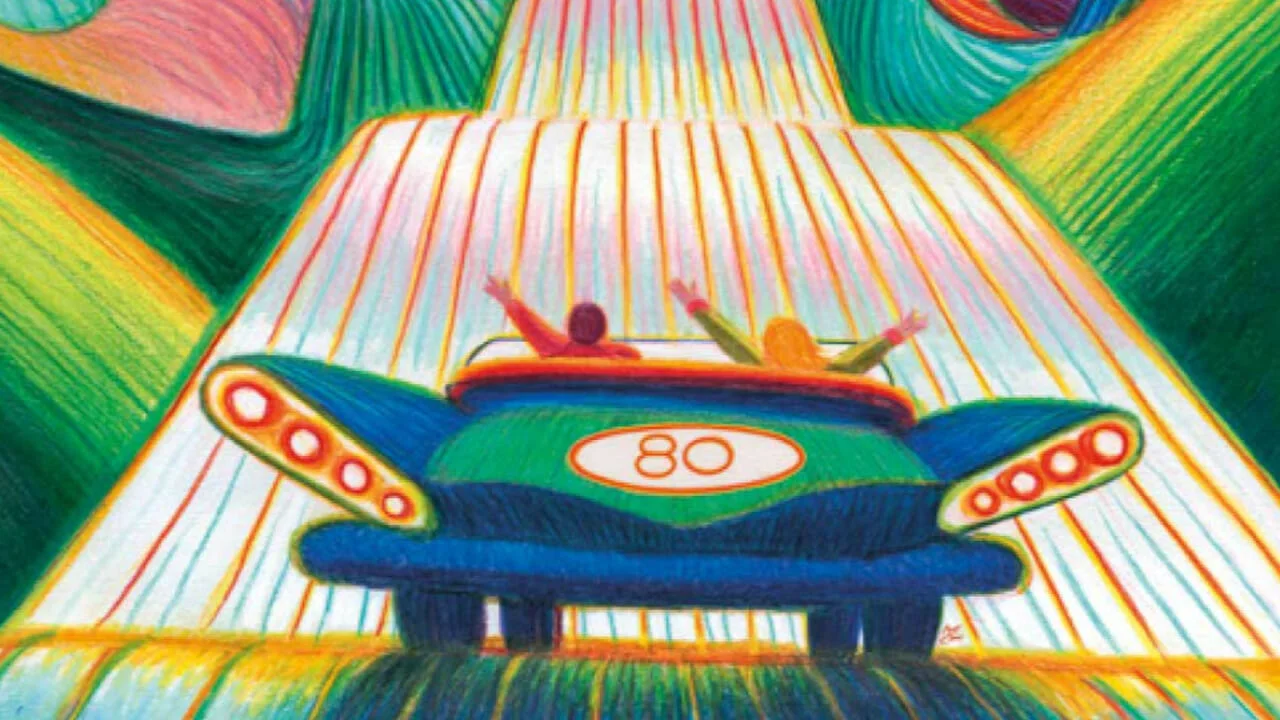

The children are sailing in a boat through a dark place, on a chocolate river reminiscent of the Styx. In the first adaptation, the scene is colored an intense red, and the parents who accompany them desperately ask when the terrible voyage will end. Moreover, in this particular case, Wonka replaces Virgilio. The chocolatier takes young Charlie/Dante on his journey through the chocolate factory and, symbolically, to heaven. In the movie, this is done by a super-fast elevator that flies with Charlie across the sky.

Each child/capital vice is punished by a kind of law that follows Dante’s Contrapasso and is explained by the songs of the Oompa-Loompa. Each piece is also inspired by a musical style from the past.

Dahl originally intended the novel for an adult readership, and the children would have been seven like the deadly sins. But to keep the novel from becoming too long, he cut three characters from the first draft. In the following version, aimed at a younger readership, the author reworked his original idea and made his journey through hell suitable for children.

Tim Burton’s version quickly became a cult classic and won several awards. The movie is the highest-grossing adaptation of a work by Roald Dahl. It is also the director’s second biggest commercial success to date, surpassed only by Alice in Wonderland.

Big punishments for little sinners

Allegories, fairy tales, and parables share the narrative purpose of imparting values and lessons. In the case of fairy tales, these teachings are usually directed at children. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory collects this legacy, creating a seemingly simple plot based on a deep and complex scheme. Just as C. S. Lewis‘s The Chronicles of Narnia combined elements of theology and Christian doctrine with a fantasy adventure, Dahl reinterprets the capital vices in a contemporary context.

Ancient iconography finds contemporary expression in the depiction of children, apt to convey how easy sin can be. Veruca, too young for carnal desire, expresses lust through her attachment to material goods. Augustus’ gluttony, on the other hand, finds its ideal context in his lust for sweets. Violetta’s pride is revealed in her inability to accept defeat, and Mike’s anger in his bad temper, typical of a child unable to relate to other people.

The references to the Divine Comedy find expression in the punishment inflicted on the children as contrapasso. Comical, exaggerated punishments that don’t endanger their health, but that can easily convey a moral: vices and sins do not lead to victory, they are mistakes that must be paid for. In the Divine Comedy, however, the contrapasso was designed for dead souls condemned to eternal pain in hell, while Dahl instilled hope in his teaching. After the children leave the factory, more or less safe, they can learn from their own mistakes and grow up to be better people. Only Charlie, humble and generous, deserves to reach a better state.

Beginning as a fairytale-like adventure, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory becomes an original reinterpretation of Dante’s work for children. An extraordinary rereading in which a sweet heaven becomes hell for those who indulge in vices. And if it’s not too early to sin, a proper punishment always offers redemption.