From Hell: How Alan Moore Turned Jack the Ripper into a Modern Myth

By

Hell is empty, and all the devils are here.

William Shakespeare, The Tempest

If there’s one work that has attempted to describe the hell not beneath our feet, but in our streets and in our institutions, it’s From Hell by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell. Originally serialized between 1989 and 1998, and later collected in a volume by Top Shelf Productions, the graphic novel spans over 500 pages.

While it’s now common knowledge that the graphic novel recounts the events of Jack the Ripper, it’s also well established that Moore didn’t simply craft a historical thriller: he created a work that blends nineteenth-century news with myth, documentation with vision, reality with nightmare. As with the superhero genre in Watchmen, here Moore tackled a codified genre to dismantle it from within. If, in Watchmen, he dismantled the myth of the hero, here he dismantled the myth of the criminal: Jack the Ripper is not a legend to decipher but a prism through which one observes an entire era.

Moore started from reality like an archaeologist, as if he were telling a story based on actual events, but then delved deeper into the psyche and the power structures that transformed a murderer into an eternal symbol. From Hell approaches the Ripper case as a means of interpreting an entire era, and beyond.

From Hell and Jack the Ripper: Beyond the Crime Story

It all begins when Alan Moore finds himself reading Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution by Stephen Knight (1976) and develops his convictions about Jack the Ripper’s true identity, after hundreds of speculations that struggle to find any basis in reality. Knight’s theory is likely among them, but Moore uses it as a starting point to tell his story.

At the beginning, the reader obviously doesn’t know who Jack the Ripper is. But, as mentioned, the investigation isn’t the focal point of the narrative, and Moore quickly establishes this by revealing who the killer is and what his motivations are: the royal physician Sir William Gull, tasked with eliminating a group of prostitutes implicated, directly or indirectly, in a scandal linked to the British royal family.

The story follows Gull from his professional past to the decision to commit the murders, outlining their preparation, organization, and execution. He is supported by John Netley, a low-level coachman who becomes his accomplice and assistant in the operations.

At the same time, readers observe the life of the victims, each shown in their complex daily lives and in the final hours before meeting their killer.

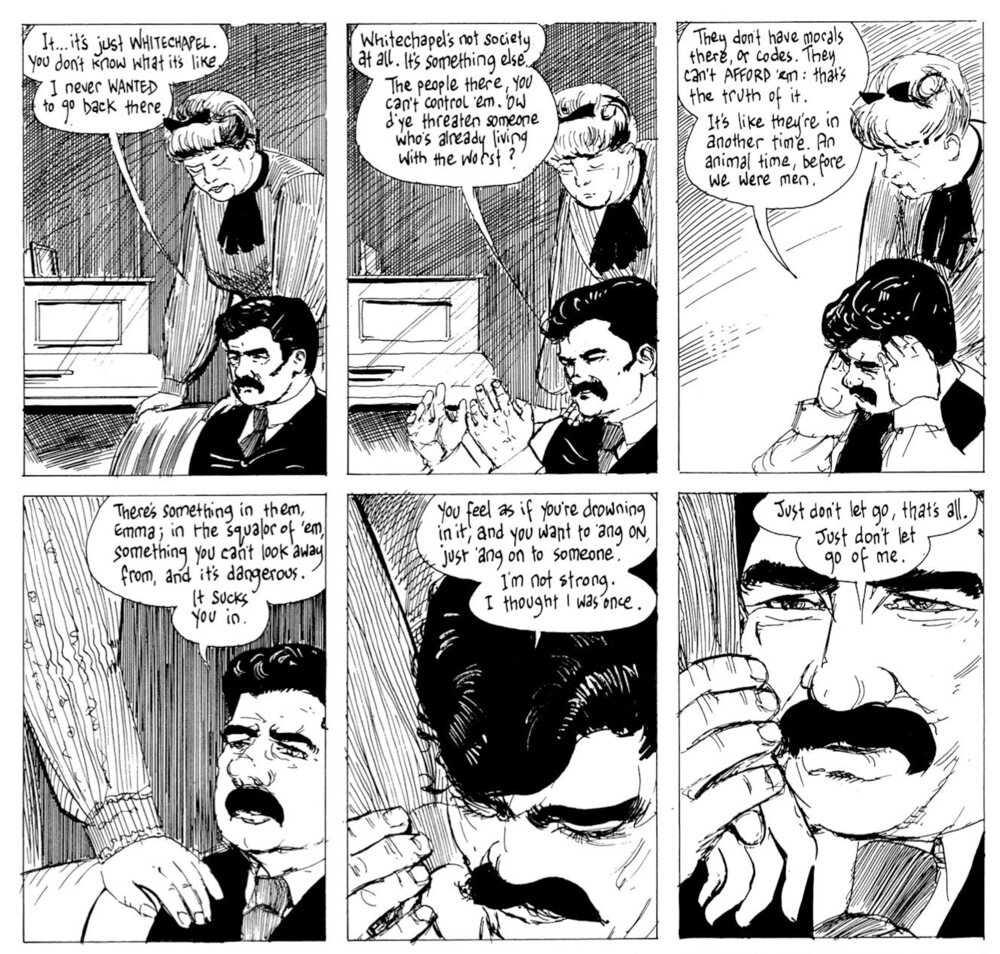

On the investigative front, readers follow the moves of Inspector Frederick Abberline, who is tasked with solving the case. Despite his dedication and experience in the Whitechapel neighborhood, his investigations are met with political pressure and misdirection, including from above, which prevent him from reaching a definitive truth or arresting the Ripper.

The story ends with Gull’s mental and physical decline, locked away and forced into isolation until his death, while the city and the world continue to live in the echoes of the unsolved mystery, destined to become legend.

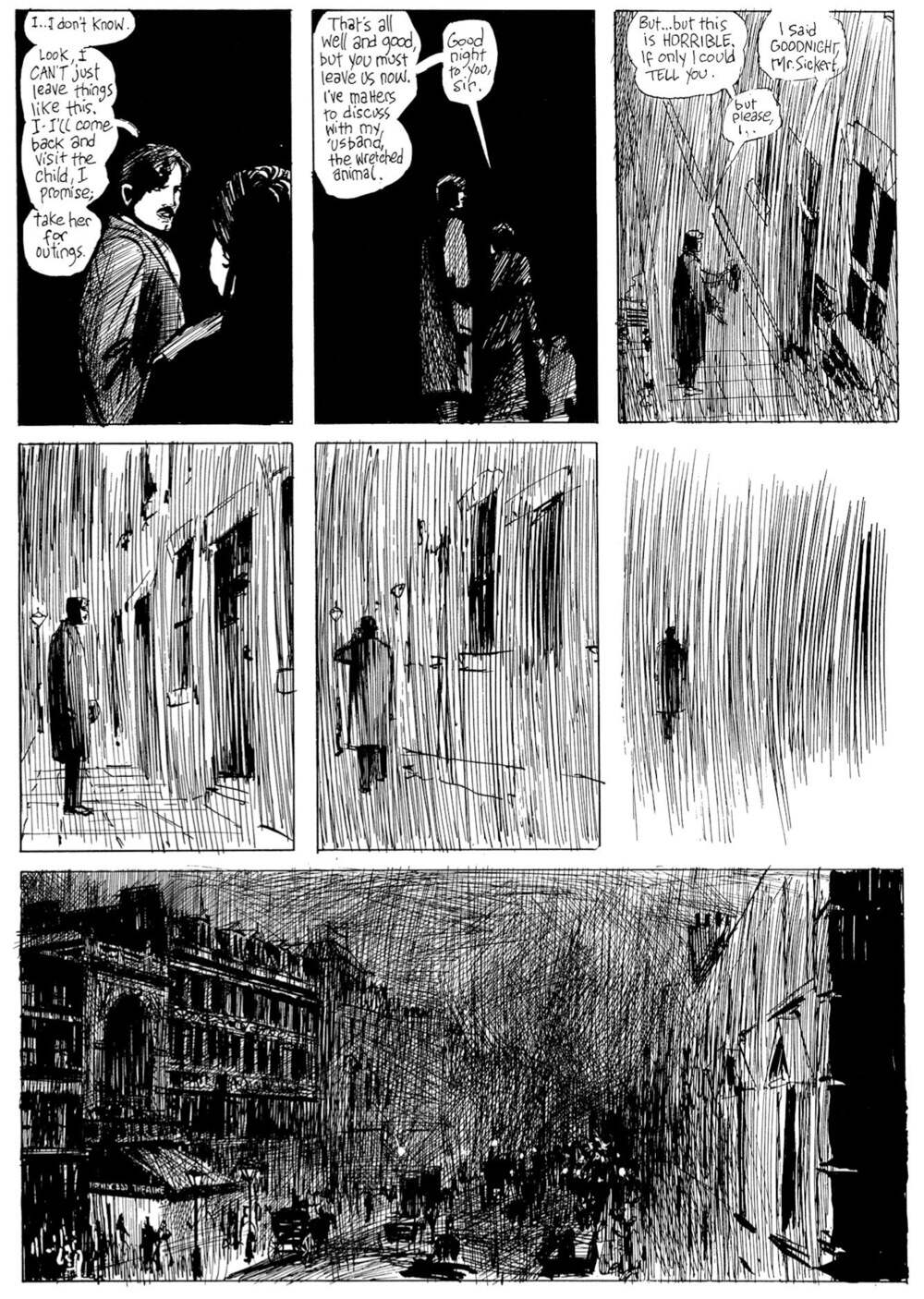

Eddie Campbell’s Art: Black and White, London, and Visual Horror

If the philosophical framework of From Hell is Moore’s work, its manifestation is Eddie Campbell’s. His scratched, almost nervous drawings help delineate the atmosphere of Victorian London. His small, regular panels construct a claustrophobic rhythm that reflects the city’s social constriction.

Black and white dominate almost entirely the book: a stark contrast, ‘corrupted’ by areas of gray and a constant sense of instability. Shadows invade the characters, blending them into the environment. There is no separation between face and wall, between body and alley: the city devours its inhabitants. The only exception is the fifth chapter, where the line becomes softer, almost watercolor-like, marking the distance between Gull’s domestic calm and the brutality of his actions.

In 2018, Campbell personally edited the color reprint, titled From Hell: Master Edition. The artist uses pastel and sepia tones to evoke the era’s patina. Many critics, however, have seen the book’s true strength in the original black-and-white, while color softens the lines whose harshness was their strength.

Sir William Gull and the Architecture of Power in Victorian England

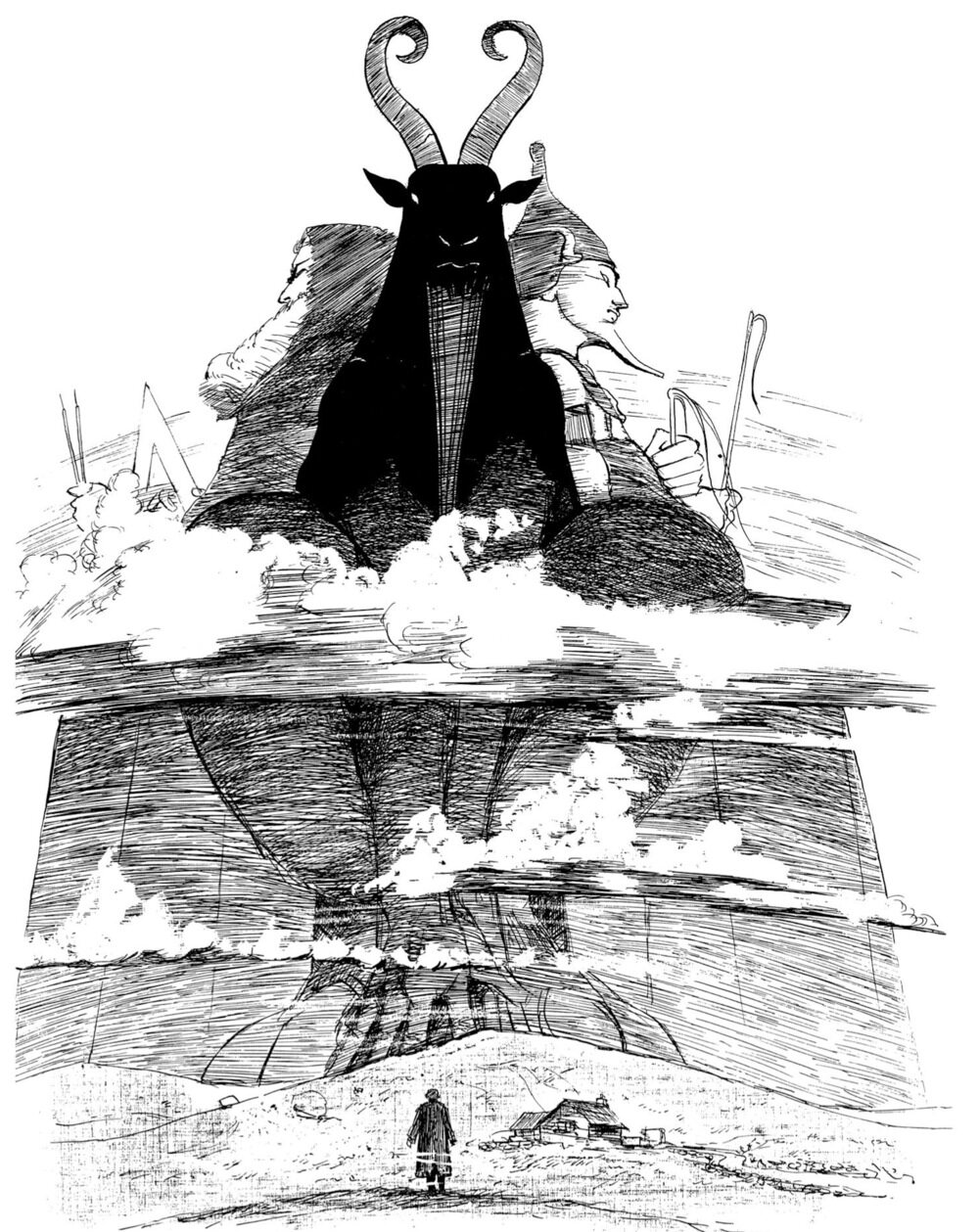

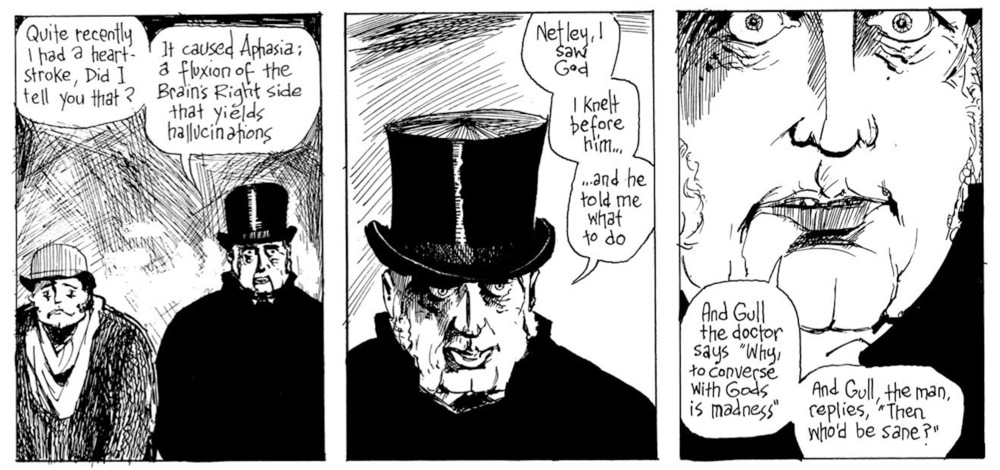

In From Hell, Sir William Gull is not only the killer behind the Whitechapel murders, but the architect of a vision: a man attempting to imprison time in a blood ritual. Alan Moore reveals his identity in the early chapters to shift the story’s focus from the who to the why. Following Gull, the reader delves into the logic of the crime as a ritual and political act, a reflection of a power that believes itself eternal and reacts violently to modernity.

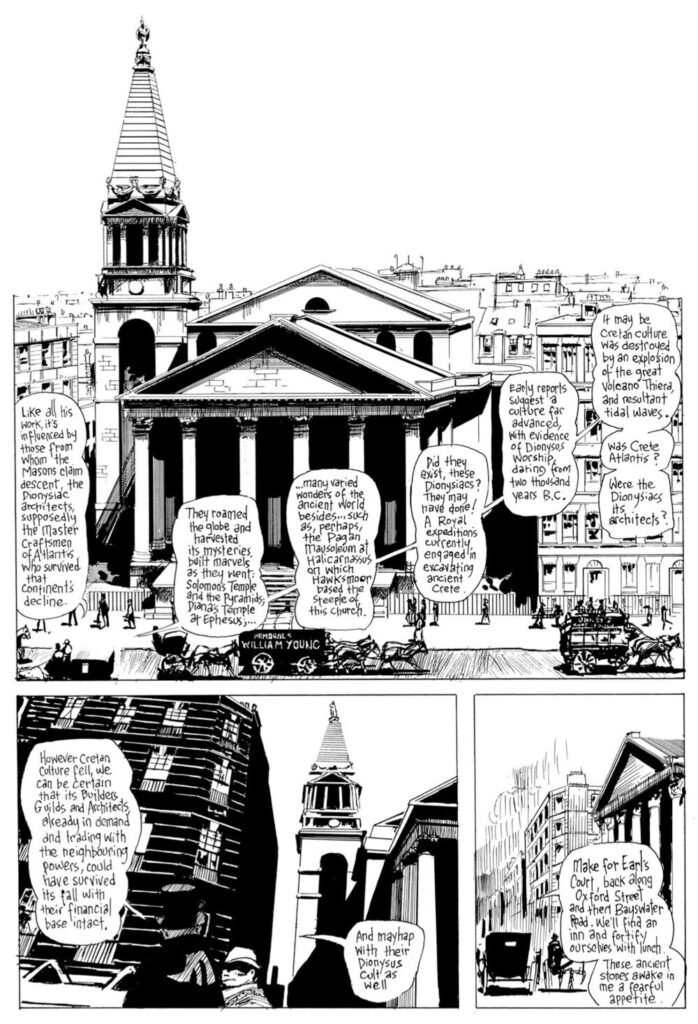

Gull received a scientific education, institutional recognition, and a Masonic creed: he represents the pinnacle of a system that is beginning to creak. And, precisely for this reason, he becomes its most extreme symbol.

Queen Victoria recruits Gull when Prince Albert marries a commoner, thus formally renouncing the crown and creating a scandal. Although it may not seem so at first, this event already encapsulates Gull’s own philosophy: the heir to the throne cannot renounce the monarchy; the “original” order must be reestablished. And Gull, in turn, acts not on impulse, in his murders, but as a priest of an order that considers women – his victims – as yet another symbol: social transformation, access to knowledge. His murders are rituals that, in Gull’s mind, serve to maintain the status quo, and women, in this context, with the ‘danger’ that they will achieve any form of emancipation, symbolize the change that must be hindered and repressed.

Jack the Ripper as Ritual: Violence, Time, and Modernity

Gull hates what he considers disorder: nascent democracy, pluralism, chaotic urbanity, and the loss of control. He hates modernity because it blurs hierarchies. He hates the rising masses and the trembling elite. In this, the murders become a desperate attempt to stop time.

In this, Gull resembles other avatars of systemic violence. Like Patrick Bateman in American Psycho, he aestheticizes the act’s ritual, transforming murder into a philosophical gesture. And much like Pablo Escobar, whose criminal figure became myth precisely because it embodied the contradictions of its society, Gull becomes the “legend” through which the city reads its own fears.

“The twentieth century. I have delivered it,” he exclaims, convinced that he has created, in blood, the new century.

Time (and its circularity and repetition – a fundamental theme also in Richard McGuire‘s Here) is another element of From Hell. On the one hand, the historical-linear, measurable one; on the other, a ritual and circular time, in which every crime reactivates an echo, a return. Thus, Gull’s visions of modern London transform evil into a force that never wanes but resounds.

In this sense, Jack the Ripper is more than a serial killer: he is the archetype of violent modernity, the first in a series that will span wars and mass murders.

In Moore and Campbell’s work, tragedy does not remain confined to the past: it becomes a metaphysical structure. Every revision, every theory about Jack, every historical reinterpretation echoes and resonates with the others: evil is not an isolated event, but an enduring temporal condition.

The irony lies in the fact that Gull himself, when he thinks he glimpses the new century, judges it to be decadent. Moore expresses the very concept that the Empire, in an attempt to save itself, generates its own demon. His crimes are the extreme metaphor of a society that prefers blood to change, and that, in attempting to stop time, merely signs its own doom.

Inspector Abberline and the Failure of Justice in From Hell

If Sir William Gull represents the delirium of Victorian power, Inspector Frederick Abberline is his human, fragile, disenchanted counterpart. In a certain sense, he is the most tragically modern character of the graphic novel.

Abberline doesn’t believe in symbols or cosmic destinies. He is a policeman, tied to the concreteness of the city of London, to the misery of Whitechapel, and to the bodies struggling to survive there. Moore portrays him as a witness rather than a protagonist: a man who observes and understands, but who can change nothing.

London is the mirror of his condition. Every street, every building, every church is part of a rigid social system, built to divide and control. The city is a temple of patriarchy: the architecture does not elevate, but crushes.

Abberline moves through London like a blood cell in a sick body: he understands that evil isn’t hidden in the alleys, but that the city itself generates it, from the royal family locking Annie Crook in a mental asylum, to the passersby who ignore the hunger and fear in the alleys.

Whitechapel is the social hell of From Hell: prostitutes are not occasional victims, but symbols of an entire class sacrificed to keep the Empire intact. When Abberline discovers that the truth can never be told, he understands that justice itself is a bourgeois illusion. His defeat is the human counterpart of Gull’s mystical ascent.

In this sense, From Hell dialogues closely with Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta. Abberline is the inverse of V: he is not the masked revolutionary who manipulates symbols to rewrite history, but the ordinary man who perceives the system’s brutality yet lacks the power to oppose it. Both understand the machinery of oppression; only one can act upon it, and Abberline is not that man.

Just as Gull attempts to transcend time, the Inspector, on the contrary, represents the city’s eternal present, the memory that remains. All he can do is watch, understand, and bear the weight of the truth.

In Abberline, Moore offers an anti-heroic portrait: modern justice is born already impotent, crushed between corrupt institutions and systemic violence. If Gull is the arrogant voice of the past that refuses to die, Abberline is the first man of a century in which truths are known but untouchable. His silent defeat is, ultimately, a little like ours too.

From Hell and the Myth of Modern Violence

From Hell is much more than a reconstruction of the Jack the Ripper mystery: it is a radical reflection on the birth of modernity and its shadows. Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell combine historical research, imagination, and philosophy to create a comprehensive portrait of Victorian England, where crime is not a deviation, but the very heart of the system.

Moore’s work is almost archaeological: the more than forty pages of annotations in the accompanying appendices illustrate, scene by scene, which parts are based on actual documents, which are narrative inventions, and where legend intertwines with history.

The two appendices that follow the story – Appendix I (notes and annotations) and Appendix II, “The Dance of the Gull-Catchers” – make it clear that Moore did not claim to solve the murders definitively, but rather to use the case as a lens to explore how society constructs its own monsters.

Jack, indeed, is not a monster bursting into an innocent world: he is the most coherent son of the age that gave birth to him. His coldness, his cult of intellect, and his obsession with control reflect the soul of the Empire and anticipate that of the century to come. With Campbell’s nervous pencil and Moore’s obsessive prose, From Hell thus becomes a journey through time and consciousness, where the monster is not the exception but the norm, and History continues to repeat its crimes, trying in vain to forget them – and must not, precisely so as not to repeat them.

Tag