Gladiator (2000) Review | Entertainment and Vengeance in the Time of the Caesars

Year

Runtime

Director

Cinematographer

Production Designer

Format

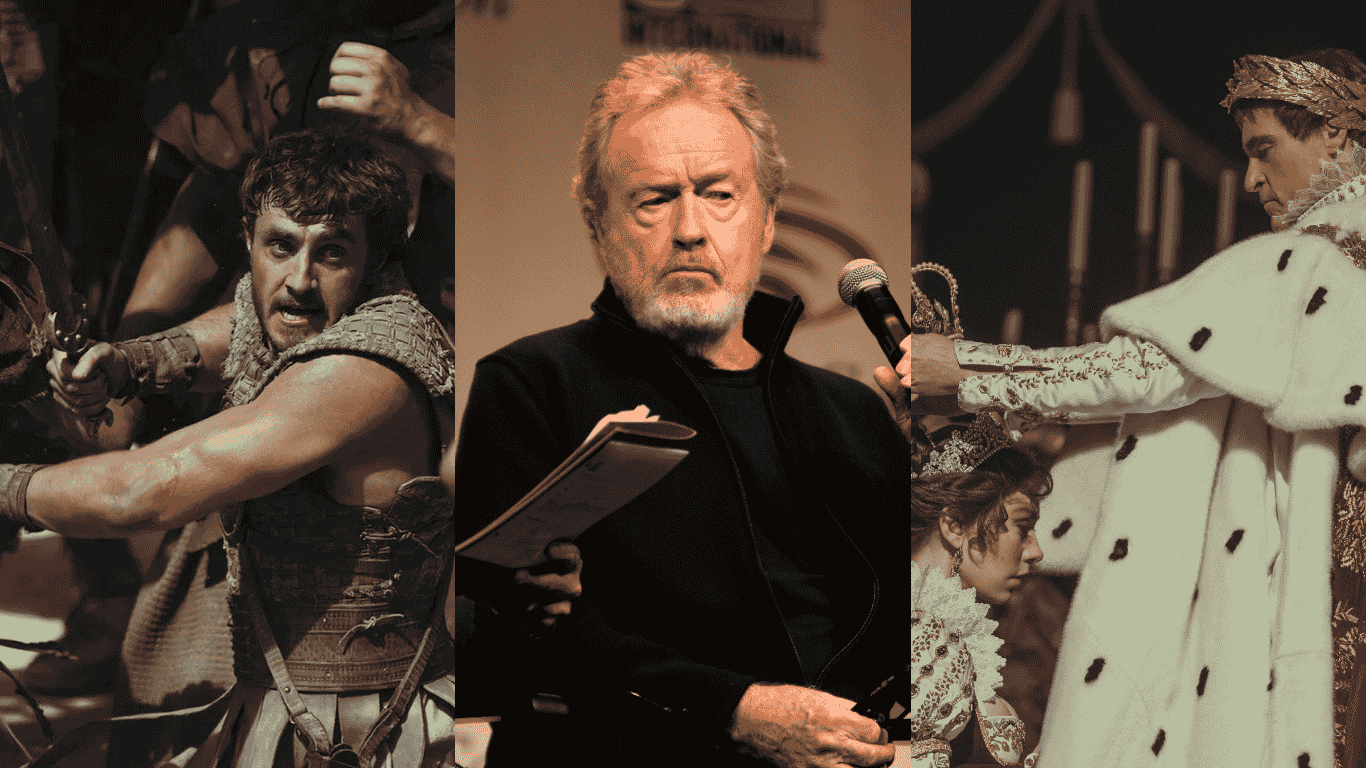

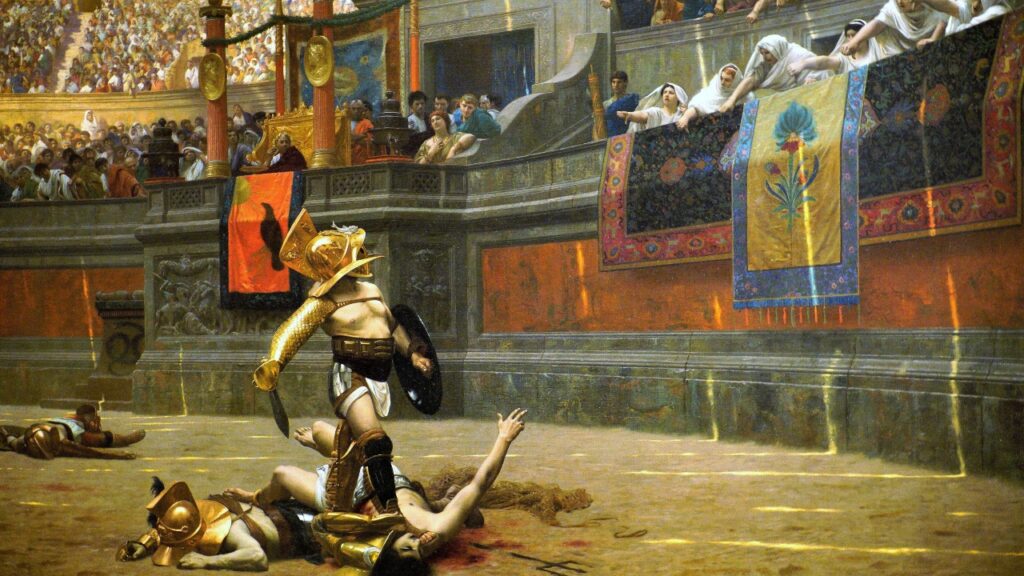

Ancient Rome never fails to exert a powerful fascination on the public imagination. It evokes a time of greatness and wonder when a single common man could rise to divine rank, and of emotions revealed in their purest and most elemental form. The same images must have passed before Ridley Scott‘s eyes when DreamWorks spokespeople showed him Pollice Verso, an 1872 painting by French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme. The anecdote goes that the painting, which depicts the winner of a Roman arena fight, convinced the British director to take the job for his 2000 film Gladiator.

Gladiator revives the great sword-and-sandal tradition. The film combines the pathos of Braveheart (1995) and the frenetic pace of Saving Private Ryan (1998) in one of the most memorable pieces of cinema, listed by The Guardian as one of the 25 best action and war films ever. Upon its release in American cinemas, it became an instant blockbuster, grossing $465.5 million, more than three times its budget. Reviews were generally positive, despite some notable outliers – Roger Ebert defined it as “muddy, fuzzy, and indistinct” – and helped the film win five Academy Awards. These included Best Picture and Best Actor for Russell Crowe, whose all-around portrayal of a Roman general launched his career. Joaquin Phoenix plays Emperor Commodus, proving his ability to play deranged and outlandish villains long before he starred in Joker.

Relying on its skilled cast and solid visual effects, Gladiator is pure entertainment and action, but without refusing to address political issues and reflect on the “unspeakable brutality with which one of the world’s greatest states conducted its business.“

- The Plot | Parable of a Roman General

- Gladiator | Epic on a Massive Scale

- Tigers in the Colosseum and More | Visual effects

- A Dish Best Served Cold | The central theme

- Empire Decline | Historic accuracy in Gladiator

- Panem et circenses | Power and entertainment

The Plot | Parable of a Roman General

The drama begins in 180 A.D. as the Roman legions battle barbarians on the fringes of the empire for the conquest of Germany. Valiant General Maximus Decimus Meridius (Russell Crowe), a beacon to his men and the protégé of Emperor Marcus Aurelius (Richard Harris), leads the army to ultimate victory. Sensing his imminent death, the aging regent elects Maximus himself as his successor and charges him with restoring Rome’s government to the Senate, the sole representative of the people. He holds his son Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix) in low esteem, fearing his aggressive temperament and unethical attitudes. However, this plan will never see the light of day. Upon learning of his father’s intentions, Commodus gets rid of the old emperor and orders the execution of Maximus and his family.

After miraculously escaping the massacre, Maximus finds himself enslaved and sold to Antonius Proximo (Oliver Reed), a gladiator trainer. In Mauretania, an African province of the Roman Empire, the former general struggles to survive, entertaining a bloodthirsty crowd and developing an insatiable desire for revenge. The occasion comes when Commodus, now at the head of the empire and unsuited to politics, opens a long period of gladiatorial games in Rome. Entering the Colosseum as an enslaved person, Maximus waits for the right moment for the showdown.

Gladiator | Epic on a Massive Scale

Since its Homeric origins, one of the defining characteristics of the epic genre has been grandeur. The greater the armies clashing in battle, the more influential the hero struggling against hardship, and the greater the awe inspired in the audience. The same logic applied to swords-and-sandals films, a genre based on the cinematic representation of mythological and historical events that was very popular until the mid-60s. The creation of these films gave life to enormous production machines, involving the reconstruction of life-size sets, frequent changes of location, and the employment of thousands of actors and extras.

Following in the footsteps of works such as Mervyn LeRoy‘s Quo Vadis (1951) and Stanley Kubrick‘s Spartacus (1960), Scott’s Gladiator doesn’t lack for scale, starting with its $103 million budget, quite remarkable for the time. Filming occurred in just five months at a frenetic pace, with four main locations in England, Morocco, Malta, and Italy. It is not clear how many actors and extras were on the set. However, it is a fact that costume designer Janty Yates, who won an Academy Award in 2001, created over 10,000 costumes. For one thing, Russell Crowe’s character alone required ten different outfits throughout the film.

Tigers in the Colosseum and More | Visual effects

As he recalled in an interview, VFX supervisor John Nelson, a two-time Academy Award winner, tried to use physical and tangible props as much as possible. For example, the two tigers roaring at Maximus in the arena were real, and the burning forest in the opening battle scene was actually set on fire. The Colosseum scenes were brought to life in a 16-meter-high replica with a 175-meter circumference, filled with 2,000 extras. CGI helped increase the scale and immersion of the architecture by adding statues, birds, and other fine details. The masterful editing of Pietro Scalia, himself an Oscar nominee, also made the rendering of spatiality and proportions possible, especially in the battle scenes. He later admitted that much of the look and pacing of the film took shape during the editing process – and that it was essential to cover up Oliver Reed’s death before filming was completed.

Not to mention the majestic soundtrack by Hans Zimmer, featuring the vocals of Lisa Gerrard, which takes historical fiction to the next level.

A Dish Best Served Cold | The central theme

My name is Maximus Decimus Meridius, commander of the Armies of the North, General of the Felix Legions, and loyal servant to the TRUE emperor, Marcus Aurelius. Father to a murdered son, husband to a murdered wife. And I will have my vengeance, in this life or the next.

Maximus (Russel Crowe)

Maximus’ dramatic speech, a favorite quote among moviegoers, expresses Gladiator‘s central theme in bold letters: revenge. It is no coincidence that the plot structure resembles that of Alexandre Dumas‘s The Count of Montecristo, the quintessential revenge story. Like Edmond Dantès, the novel’s protagonist, Maximus quickly moves from a rosy future – the longed-for return to home and family – to hell on earth – the loss of his loved ones and slavery. Anger and grief turn him into an almost divine killing machine capable of anything to get revenge.

Despite the gigantic technical side, Crowe is Scott’s creation’s true center of gravity, holding the screen “with such assuredness and force you simply can’t rip your eyes away from him.” As he recalled in an interview for Variety, he insisted on personally filming some of the more dangerous scenes – including the fight with the tigers – and frequently improvised, such as the infamous line: “At my signal, unleash hell.” Rumor has it that he also suffered some broken bones. Considering all this, it is no surprise that the Academy awarded Crowe the Oscar for Best Actor.

Empire Decline | Historic accuracy in Gladiator

Though Crowe’s muscular performance and the high-intensity battle scenes grab most of the audience’s attention, the historical framework in which the characters move deserves mention. As so often happens in this genre, Gladiator sparked a hunt for inaccuracies in depicting ancient Rome – here is just one example of a thorough historical analysis. Anyway, apart from some poetic licenses, Scott managed to effectively convey the moral and political decline of the Roman Empire in the last years of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty.

“There was once a dream that was Rome,” says a weary Marcus Aurelius in the film’s incipit, alluding to a world long gone and a whole system of values that survives in fewer and fewer people. One is Maximus, a man in one piece devoted to his homeland, his family, and the last stronghold of the mos maiorum, the ancestors’ tradition. The scenes in which he touches the wheat and lets the sand run through his fingers describe a humble man who holds on to the earth but also knows that he must return to it. On the other side is Commodus, who represents the new, advancing but neglectful of past teachings, ambitious but unbalanced and easily misled. As the cast confirmed, Phoenix’s interpretation profoundly influenced the Game of Thrones cast and showrunners as a model of degenerate and tyrannical power.

The clash between Maximus and Commodus, both sons of an empire in disarray, is thus a confrontation between two different worldviews, which Scott skillfully charged with pathos and anticipation, as he would do later in The Last Duel and The Duellists. All viewers know this is how the film will end, but each one eagerly awaits it.

Panem et circenses | Power and entertainment

Of course, this whole contrast of values is a secondary way of interpreting Gladiator. The focus is on the action, the here and now, and the spectacle that the character of Maximus provides in one fight after another. Speaking of spectacle, the review in the Italian film encyclopedia Il Morandini offers a curious interpretation:

The DreamWorks mega-film is a fantasy-historical parable about the society of spectacle and the use of show business by power – all power, including religious power – to influence and dominate the masses.

Il Morandini 2020 (translated by the author)

Such a cue opens up a suggestive similarity between the historical period in which the action takes place and the present day, where entertainment, with due distinctions, still plays a fundamental and often underestimated role in distracting people. The French philosopher Guy Debord coined the term “society of the spectacle“ to describe a world in which shows are “the oil which keeps the engine running, the viewer passive, lost in the stream of images.” Debord actually refers to contemporary society, but it is easy to find the same pattern in Scott’s Gladiator, which is in imperial Rome.

The film shows the fluid and almost symbiotic relationship between power and entertainment, with the gladiators being nothing more than a political device to keep the people subservient. The majesty of the games, underscored by the use of golden tones and aerial shots of the Colosseum – not coincidentally reminiscent of the camerawork of modern sports games – is a piece of scenery created to conceal a moral vacuum and the absence of political design. The character of Senator Gracchus (Derek Jacobi) reveals Commodus’ sleight of hand with eloquent words:

I think he knows what Rome is. Rome is the mob. Conjure magic for them, and they’ll be distracted. Take away their freedom, and still, they’ll roar. The beating heart of Rome is not the marble of the senate; it’s the sand of the coliseum. He’ll bring them death – and they will love him for it.

Senator Gracchus (Derek Jacobi)

Again, Gladiator‘s primary goal is not to provoke political reflection in its audience. But its greatness also rests on its ability to bridge two distant historical periods, to draw parallels as only a filmmaker like Ridley Scott could.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic