Game of Thrones Review | The fantasy show that changed the rules

Seasons

Runtime

When you play the game of thrones, you win or you die.

Cersei Lannister (Lena Headey), Game of Thrones 7×01

Since the beginning of human history, every man has fought for power, which doesn’t just mean physically clashing in war, but acting with subterfuge, conspiracies, alliances, and betrayals. This story has remained nearly the same right up until the present day, as have the dangers of taking part in it. As Game of Thrones clearly shows, participating can lead to self-compromising, but if someone is not a skilled enough player, they can even lose their own life.

Created by David Benioff and D.B. Weiss and produced by HBO, the series is based on George R. R. Martin‘s saga A Song of Ice and Fire. Its 8 seasons aired from 2011 to 2019, and it gained several nominations and awards, including 59 Emmy Awards. Moreover, it entered the Guinness World Records as the Most Pirated TV Program and the Largest TV drama simulcast.

Despite the critics’ reaction to the final season, Game of Thrones remains a turning point in the history of TV shows and the fantasy genre. The complex and multilayered storylines, the depiction in shocking scenes of violence and sex and the total disregard for the characters’ lives. The use of epic scenes and immense battlefields, typical of cinema, had never been seen on a TV show before. Game of Thrones also enters into a connection with classical culture and philosophy. As in ancient myths, the events and characters in Westeros enact moral and ethical dilemmas, giving no answer but the personal choice.

A story of blood, dynasties, and power

The story begins with Eddard Stark (Sean Bean), known as Ned, Lord Protector of the North, welcoming his old friend, King Robert Baratheon (Mark Addy), to Winterfell. Robert informs him that his closest advisor, his Hand of the King, has passed away, and he wishes Eddard to follow him to King’s Landing to become his councilor. Stark is not convinced but ends up accepting when given an excellent offer: Robert suggests a marriage between his heir and Ned’s oldest daughter, Sansa (Sophie Turner); so, they leave for the south. Before their departure, he says goodbye to Jon (Kit Harrington), his illegitimate son, who is joining the Night’s Watch. He will protect the realms of men, divided from the barbarian lands by the Wall, an enormous barrier built with rock, ice, and spells.

Having just arrived in the capital city, he discovers why the king needs a faithful advisor. His biggest concern comes from across the sea, where Daenerys Targaryen (Emilia Clarke), daughter of the previous King, is going to marry Khal, Lord of the Dothraki. Nobody could imagine that the girl would receive three dragon eggs for her wedding. Dragons are considered extinct, but Daenerys is the last heir of the House of the Dragon: her blood remembers her origins, and her spirit the throne she never saw.

The storylines multiply, new characters join the match, and different plans intersect. Any curvy path, though, seems to lead to the same question: who will sit on the Iron Throne?

The man who passes the sentence should swing the sword

Game of Thrones distinguishes itself from most of the other fantasy sagas by keeping fantastical elements at the narrative edge. Martin himself declared he took inspiration from actual historical facts, particularly the Hundred Years’ War and the Wars of the Roses. At the same time, the Wall shows many similarities with Hadrian’s Wall as well.

Until the very end, the real crux is on the fight for power, which makes the show’s dynamics much more similar to those, for example, in The Crown or House of Cards.

The real question, therefore, is who possesses the right qualities to reign, and what these qualities are. In Game of Thrones, one could think that the best ruler is the one who doesn’t desire to reign, at first. Yet, the development of the story suggests that a reasonable person often isn’t also a good ruler, as a good leader should be able to make debatable choices.

Game of Thrones follows the Machiavellian theory and the motto “the end justifies the means”, which implies that not every end is right, and power itself is never a proper end. A good ruler must always consider others’ interests, not just what’s right or wrong. Moreover, Machiavelli affirms that sometimes a good person has to lie, break vows, kill, all in the name of a superior good. This concept is echoed in Game of Thrones, continuously challenging the audience’s questioning about ethics and morality, as it wonders which is the right way to become a good person before becoming a good ruler. Just as for Harry Potter‘s Albus Silente, who in the end made some choices not so much for Harry‘s well-being, but for the Greater Good, good does not always mean right and vice versa.

At the edge of the battle

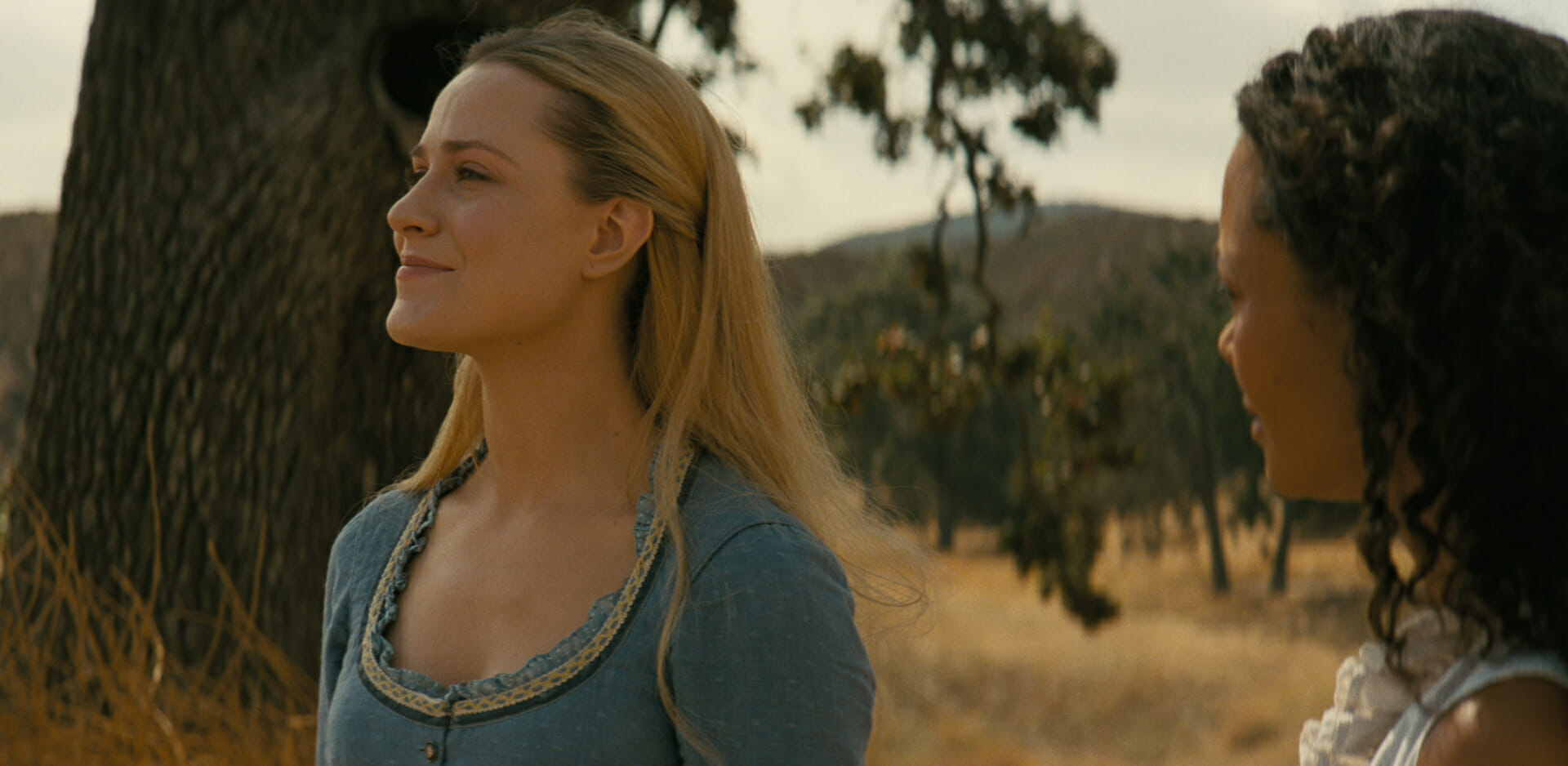

In the past, women were considered to be second-class beings, a means of reproduction and exchanges, and their marriages were often only political agreements. The show portrays in a very realistic way female conditions, from those of prostitutes to queens. The best bidder can buy Sansa, along with Daenerys and Margery Tyrell, to allow a man to gain power. However, they recall a multifaceted figure that, not by chance, belongs to a family linked to Machiavellian politics: Lucrezia Borgia. Born into influential families, they were used as trade goods and soon became aware of the power they could exercise.

Other outcast characters acquire increasing importance. Many never aim to have power, only to gain public respect and appreciation, but most of the time they are denied this. They’re clandestine children, hidden in slums or hated by legitimate wives. They’re nobles of recent appointment, mad people to look at with compassion. It’s the case of Jon Snow, bastard son who looks for dignity in the Night Watch. Or Littlefinger, willing to do anything to join the fight for power, and Hodor, described as a simple-minded, gentle giant. They aren’t very different from Shakespeare‘s Edgar and Edmund of Gloucester from King Lear, or Macduff and Lady Macbeth.

All those outcasts are always underestimated, but being underrated is their main strength, making their actions unexpected. Martin, and consequently the show, shed light on the importance of determination over names. In some cases, they want to show how this will make those who are ignored stronger than those who were born important; and in another, they demonstrate that everyone has a role in the main game.

Between technique and aesthetic

Reflecting the novel’s structure, the show follows multiple storylines and points of view. This is a complexity that mirrors Ramin Djawadi‘s multi-thematic soundtrack. In Game of Thrones, it also becomes a means to instill the characters’ morality and traits. Good characters are linked to major tonality and perceived as balanced, powerful, and steady, while minor tonality and irregular rhythm introduce evil characters, triggering anxiety and pain. As music connects with the subconscious, and some aspects of human morality are instinctive, melodies suggest honesty and deceitfulness.

Game of Thrones brought to television a look more commonly associated with films, along with attendant care for details and cinematography. Linking in to ancient Greece’s epic tales, it also makes full use of glorious clashes that grant moral immortality. Besides being an essay in cinematographic technique, common in blockbusters such as The Last Samurai and Troy, battles highlight the differences between good and evil. The physical appearance of a “bad character” is often disgusting, or at least it inspires no trust at all. This aspect is evident in films such as The Lord of the Rings, where men and elves face horrific Uruk-hais.

Many philosophers dealt with the theme of beauty and its connection with goodness and truth. Plato and Thomas Aquinas believed that true beauty can’t but be linked to a superior truth; it applies, for example, to the Greek hero of the Iliad, Achilles.

In Game of Thrones, this is no longer valid. Tyrion Lannister, the deformed son of the royal family, is one of the most intelligent and cunning men, and rarely acts not for the good of the Seven Kingdoms. On the other hand, for example, his sister, the beautiful Cersei, is famous for her beauty, but also for her pride, her envy and her selfishness.

The bequest of a massive turning point

Game of Thrones required the use of over 15,000 liters of fake blood, over 12,000 wigs, nearly 13,000 background actors, and 40 different companies worked only on the special effects. The concept of the blockbuster finally arrived in the world of television once and for all. The massive merchandising was even accompanied by unusual items, such as the official cookbook called A Feast of Ice and Fire.

Game of Thrones represents a revolution from the narrative point of view too. Ned Stark is immediately perceived as a protagonist, honest, just, and brave; then, his killing at the end of the very first season represented a shock: the hero died at the beginning of his adventure. The rules of the narrative game changed. It also made it clear that characters’ lives weren’t meaningful: the throne, and the power it represents, is the only protagonist of Game of Thrones.

Moreover, it wasn’t the only shocking element of the show. Before Game of Thrones, nobody dared to display a similar amount of blood, rotting wounds, violent deaths, explicit sex, and even incest. All those ingredients resulted in an increasingly astonishing show, as the astounded audience couldn’t take its eyes off the screen.

In the end, however, as the show overcame the novels’ narrative, many noticed a loss of quality. The audience criticized in particular a general impoverishment of the screenplay and a bland attempt to balance through special effects. Despite that, the bequest of this production marked a point of no return. There was a specific idea about TV shows before Game of Thrones, and a new one after Game of Thrones. Neither of these criticisms deterred the fanbase, as proved by House of the Dragon‘s success, and the will of HBO to produce another prequel, A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms.

As a mirror of reality

Game of Thrones doesn’t owe all its success to the high rate of violent or sexual scenes, though, nor to its ability to shock the audience. The hype and the general involvement widely depend on the way it reflects real life.

Yet, there’s another still actual undefeated enemy: death. The Many-Face God servants say “Valar Morghulis”, so as Trappist monks recited “Memento Mori”. Death as a concept is an absolute co-protagonist in Game of Thrones, embodied by the White Walkers, icy incarnations of non-life. As in reality, in front of death, the social pyramid vanishes, and humanity’s big and small battles disappear. So, as depicted in historical fiction, such as The Decameron or The Betrothed, death affects both the poor and the noble in the same manner. The only way to escape the inevitable is to fulfill oneself and become the creator of one’s destiny.

Tag