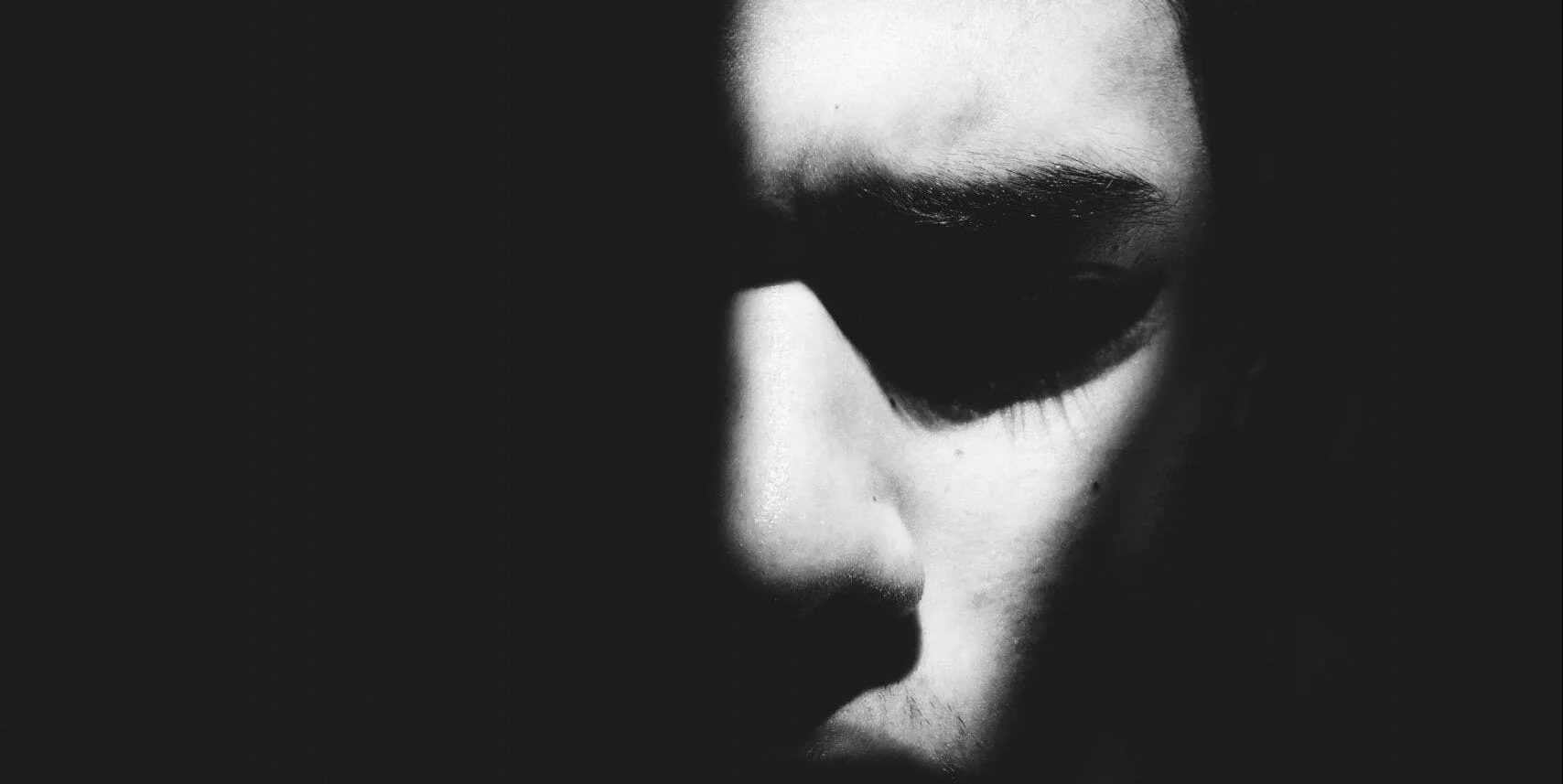

A History of Violence | Shadows of a shining knight

Year

Runtime

Director

Writer

Cinematographer

Production Designer

Music by

Country

Format

Genre

A History of Violence marks the return of Body Horror auteur David Cronenberg to American Cinema. Based on John Wagner and Vince Locke’s eponymous graphic novel, the subject matter is, by the director’s standards, quite traditional. The reason why it fits so seamlessly into the filmmaker’s corpus is that – as writer J. G. Ballard asserts in his review of the movie – “he has remained faithful to his central project. His films constitute a sustained autopsy into the nature of existence”. For A History of Violence, Cronenberg chooses to operate under the emblem of subtlety.

Tom Stall, a loving husband and father, leads a quiet life in small-town America. After killing two criminals to prevent an armed robbery in his diner, he becomes a national hero in the eyes of the media. This undesired popularity brings to town a bunch of gangsters, who claim that the hero is in fact a former colleague of theirs in disguise. The man soon finds himself spiraling into violence, which threatens to drag his family down with him.

Shadow of a Model Citizen

It’s no coincidence that Cronenberg gave the part of a hero-under-duress to Viggo Mortensen. The actor had just reached stardom by playing the shining knight Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings and was eager to escape typecasting. The ambiguity that partners appearances is taken to extreme consequences. A History of Violence aims at the most obscure part of the human personality, what Carl Jung called the Shadow. And it shows how it can be even darker in a model citizen that has ignored it so as to achieve normality.

In this construction-destruction of identity, an obsession of Cronenberg’s, relationships play a big part. The director called the movie “my version of Scenes from a Marriage”. In his eyes, Ingmar Bergman’s 1973 miniseries also conceives the union as a “performance art piece” where the spouses adjust their true selves to one another. No wonder that when the hero’s past casts shadows on his surroundings, his wife starts to question his identity. And as is customary in Cronenberg’s movies, this process of questioning and adjustment passes through sexuality.

Similarly, the hero’s teenage son starts to question his father’s role as head of the family. And as he fails to maintain his bonds of control, unless by deploying violence, Tom Stall proves to be Patriarchy embodied. And this failure seems doomed to pass down from generation to generation.

History is Violence

There are no second acts in American lives.

Francis Scott Fitzgerald, The Last Tycoon

The film narrative essentially maximizes universality along with tension. Thus, the titular history of violence is not just the plot, but the history of America. By shattering a vital part of the American Dream – the myth of the second chance – the movie reminds us that the United States has laid its foundations on violence. And it suggests that just because it practices it less inside its borders, it doesn’t mean it has forgotten how. But the commentary can address Western Civilization as a whole, as the many Biblical archetypes in the film show.

The past that casts shadows is indeed everybody’s because it is not temporal but psychological. And everybody’s hands will never be clean of the trauma. Because the trauma could be – to quote Ballard’s review again – “the experience of being alive”.

Shedding Light on the Shadow

At first glance, A History of Violence seems drenched with clichés, starting with the mistaken identity trope canonized by Alfred Hitchcock. In fact, Cronenberg overturns them to sarcastically come back around onto their genres of origin. The resulting new amalgam of gangster, western, noir, and family drama exploits the déjà-vu effect it has on the viewer to disclose the mythmaking facade of American Cinema. And since it’s the foundation of these “self-heroicizing, self-justifications we sell to the world” (as critic Manohla Dargis calls them), violence is the prime target.

The mise-en-scène of violence is relentless, but detached. It indulges the viewer’s morbid appetite for brutality, but then lingers on its repulsive consequences. Thus, by rejecting catharsis, it forces the viewer to acknowledge the perversion of it all. This estranging operation is similar (albeit much less overt in its self-awareness) to Michael Haneke‘s Funny Games movies.

However, Cronenberg’s ultimate intent is not ethical (unlike Haneke’s) but maieutic. The protagonist’s past casts shadows on the viewer as well. But by shedding light on their existence, the movie brings such latent feelings right in front of our eyes, where they sometimes need to be.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic