Civil War, by Alex Garland Review | They Shoot Presidents, Don't They?

Year

Runtime

Director

Writer

Cinematographer

Production Designer

Country

Format

When it comes to dystopias, timing is everything. And in times of ideological polarization and fear of political violence, Alex Garland‘s Civil War, one of A24‘s highest-costing and grossing movies to date, falls just right. Civil War is a sort of middlebrow counterpart to the season four finale of The Boys (named initially Assassination Run, a title eventually dropped in the aftermath of former President Donald Trump’s assassination attempt). And as the U.S. 2024 Election Run gets ever more tense, the movie becomes more relevant.

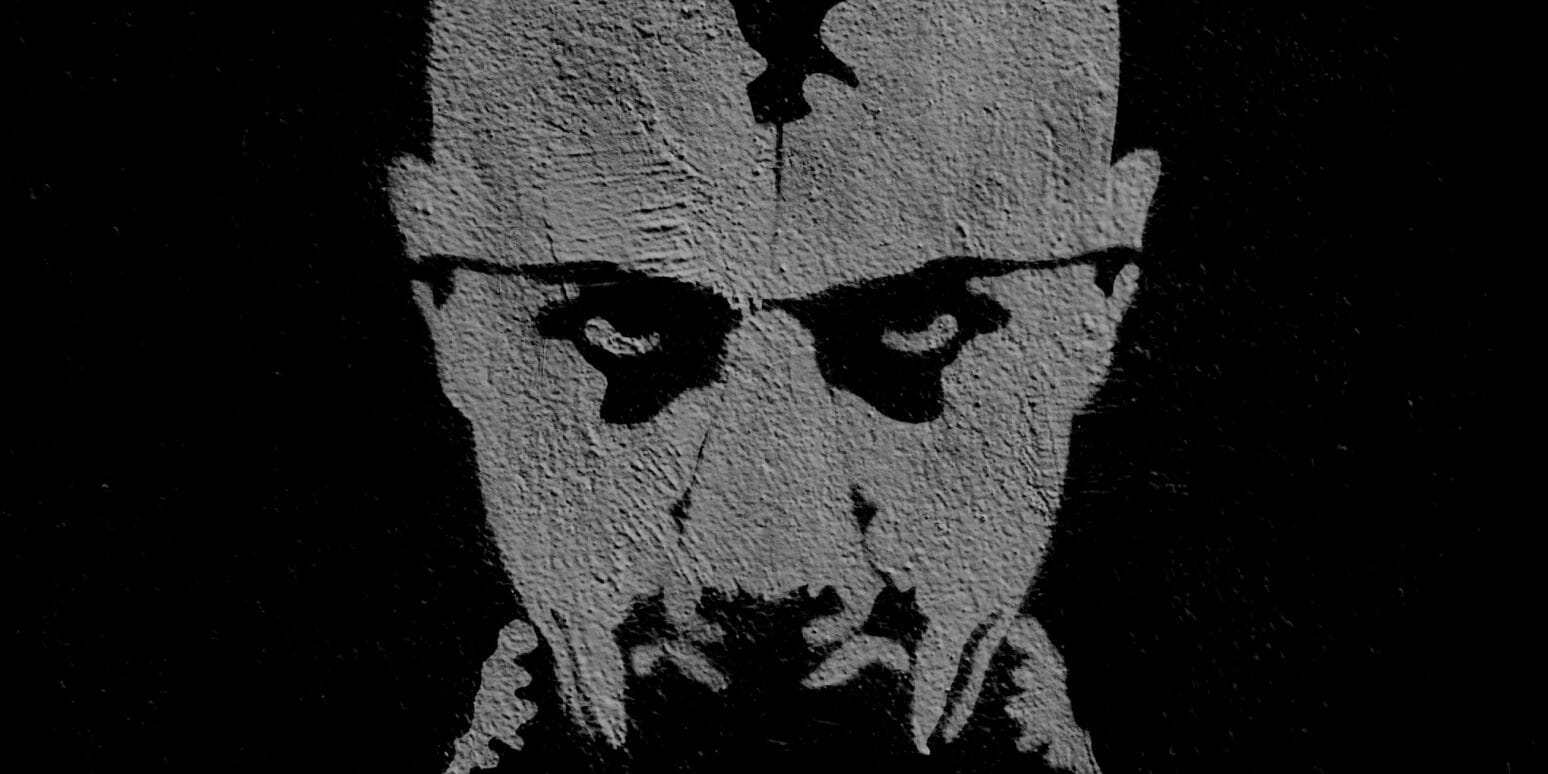

The United States is at the end of a dirty civil war. The “Western Forces,” an alliance between secessionist California and Texas, are marching on Washington D.C. to overthrow a dictatorial President (Nick Offerman) lost in his propaganda. Seasoned reporters Lee Smith (Kirsten Dunst) and Joel (Wagner Moura) are on a run to reach the capital before the counter-coup and become the authors of the last picture and interview of the last President of the United States. In a moment of audacity, Jessie Cullen (Cailee Spaeny), a young photojournalist wanna-be, jumps on the bandwagon. But she will soon find that war is way more intoxicating than expected.

- “A Curious Volume of Forgotten Lore”

- A Nation of Taxi Driver(s)

- Fear of Missing out the End of the World

- The Act of Shooting

“A Curious Volume of Forgotten Lore”

Having an enemy is important not only to define our identity but also to provide us with an obstacle against which to measure our system of values and, in seeking to overcome it, to demonstrate our own worth. So when there is no enemy, we have to invent one.

Umberto Eco, Inventing the Enemy

Upon its release, Civil War was instantly criticized for lacking a realistic backstory for the titular conflict. How come Texas and California joined forces? What did the President do to compromise the nation to such a scale? On a closer look, none of these contingencies matters.

The idea of another American civil war concerns Garland (“War is God,” to quote Cormac McCarthy‘s 1985 novel Blood Meridian) rather than its actual possibility in the foreseeable future. In this sense, having the quintessentially Democrat and Republican states join forces is not just a tactic to not alienate audiences from different political aisles. It is a jump into abstraction, a commitment to “opaqueness” (as Garland said in an interview). And a call for the viewer’s responsibility to make sense of what they see beyond facile associations.

A Nation of Taxi Driver(s)

The writer-director also claimed (in an A24 featurette) that his is “a war film in the Apocalypse Now mode”. But even though Francis Ford Coppola‘s magnum opus is the primary reference, Civil War also has a lot in common with Kathryn Bigelow‘s The Hurt Locker (2008) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012), and Brian De Palma‘s Redacted (2007).

With Bigelow’s works, Garland shares the idea of war as a drug, an addicting experience for the PTSD-fuelled (and socially alienated) people taking part in it. The worst thing that could happen to them is not defeat but peace. With De Palma, the notion that, in the contemporary age, images are not just a representation of reality but full-fledged actual events that actively influence the unfolding of history, especially during wartime. With all three, a gritty visual style (cinematographer Rob Hardy shot on a prosumer digital camera) that evokes an aura of photojournalism.

Redacted, The Hurt Locker, and Zero Dark Thirty came out in the context of the “war on terror.” It would not take long for Hollywood (its provocative side, at least) to question the meaning of such war, as U.S. interventions in South-West Asia soon proved to be not the response to an existential threat but the outlet of an existential dread. In times of peace, the question became inescapable: What is even America? The war on terror served as a viable answer.

In Civil War, one could say that the hunt for the dictatorial President of the United States took the shape of the one for Bin Laden. The enemy, the terror to wage war upon (“the horror… the horror…”) has always been in the mind of those who use war as a substitute for introspection. Eventually, a nation that seems to find meaning only in war – fighting in search of an answer, fighting because fighting is the answer – cannot but turn against itself in a grotesque form of self-scrutiny. A nation of Taxi Drivers.

Fear of Missing out the End of the World

Oh, feed my eyes…

Now you’ve sewn them shut.

Alice In Chains, “Man in the Box” – from grunge album Facelift (1990)

“We don’t ask. We record so other people ask”. This is the explanation the older reporters provide to their young companions for their cold-hearted professionalism in the face of the horrors of the civil war. But it is just an excuse. What on the surface may seem like an act of responsibility – sticking to the facts, recording them in times of indifference – is, in fact, a surrender to adrenaline.

Lee and Joel are just like Apocalypse Now‘s Willard, war-addicted veterans with no home to come back to. The anticipation for their journey is the same, only in the case of Civil War there is no one waiting at the end of the river. No poet-warrior harboring the secret meaning of the war, only a talking head dethroned of his broadcasting privileges. The reporters’ mission is meaningless, like the civil war as a whole. All that remains is the thrill of it.

Civil War closes on one of Jessie’s analog photographs, which is slowly coming into development. In a way, this shot matches the one that opens Christopher Nolan‘s Memento (2000). A man shakes a Polaroid picture in reverse motion, and the image slowly fades away, symbolizing the thematic core of the movie: the importance of memory for the setting of identity and amnesia as a metaphor for the loss of self. While opposite on a literal level, the closing shot of Civil War is on the same paradoxical page. In the story’s context, what seems like a victory for journalism takes on a bleaker nuance. Photography and journalism can and do fix historical events into collective memory. Yet, the thrill of those who won the chance to depict, participate, or witness such events overshadows their meaning. The picture is clear, but the eyes are wide shut.

The Act of Shooting

“Shoot me.”

A young filmmaker about to turn into a living dead begging to be killed while getting filmed in the process – in George A. Romero’s found-footage horror flick Diary of the Dead (2007)

As the plot unfolds, the young protagonist becomes more invested in the conflict she’s reporting. She downright joins the military maneuvers, wielding her camera as a rifle. Yet, she is no soldier. She is just the front-runner for the ultimate videogame: civil war in the country that used to lead the Western Civilization.

Her shooting frenzy is nothing extraordinary. She is no different than the no. 1 fans of the latest music sensation over-spending time and money to be in the front row for the world tour of their beloved artist, only to then record the entire thing with their phone instead of watching it with their eyes. The point is not to record the experience – the images are not meant to be rewatched once the event ends. Nor is it to share it – the images are shared indeed, but the FOMO-induced interest for them is short-lived. The images themselves mean nothing. They are just the byproduct of a satisfied need, the collateral effect of the act of shooting.

The digital landscape is the other, closer dystopia portrayed by the movie – along with the titular civil war. If the President of the United States were killed in front of anyone, their first reflexive response would be to snap a picture. In this addicted-to-images scenario, the relationship between authenticity and reproduction is permanently overturned. The only way to relate to reality is through its representation. The only way to fully enjoy (or even so much experience) anything is through an image-producing device. The camera as a filter, drug administrator, and looking glass: I shoot; therefore, I am.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic