Taxi Driver | The Dark Night of the Psyche

Year

Runtime

Director

Main Cast

Writer

Cinematographer

Production Designer

Music by

Country

Format

Genre

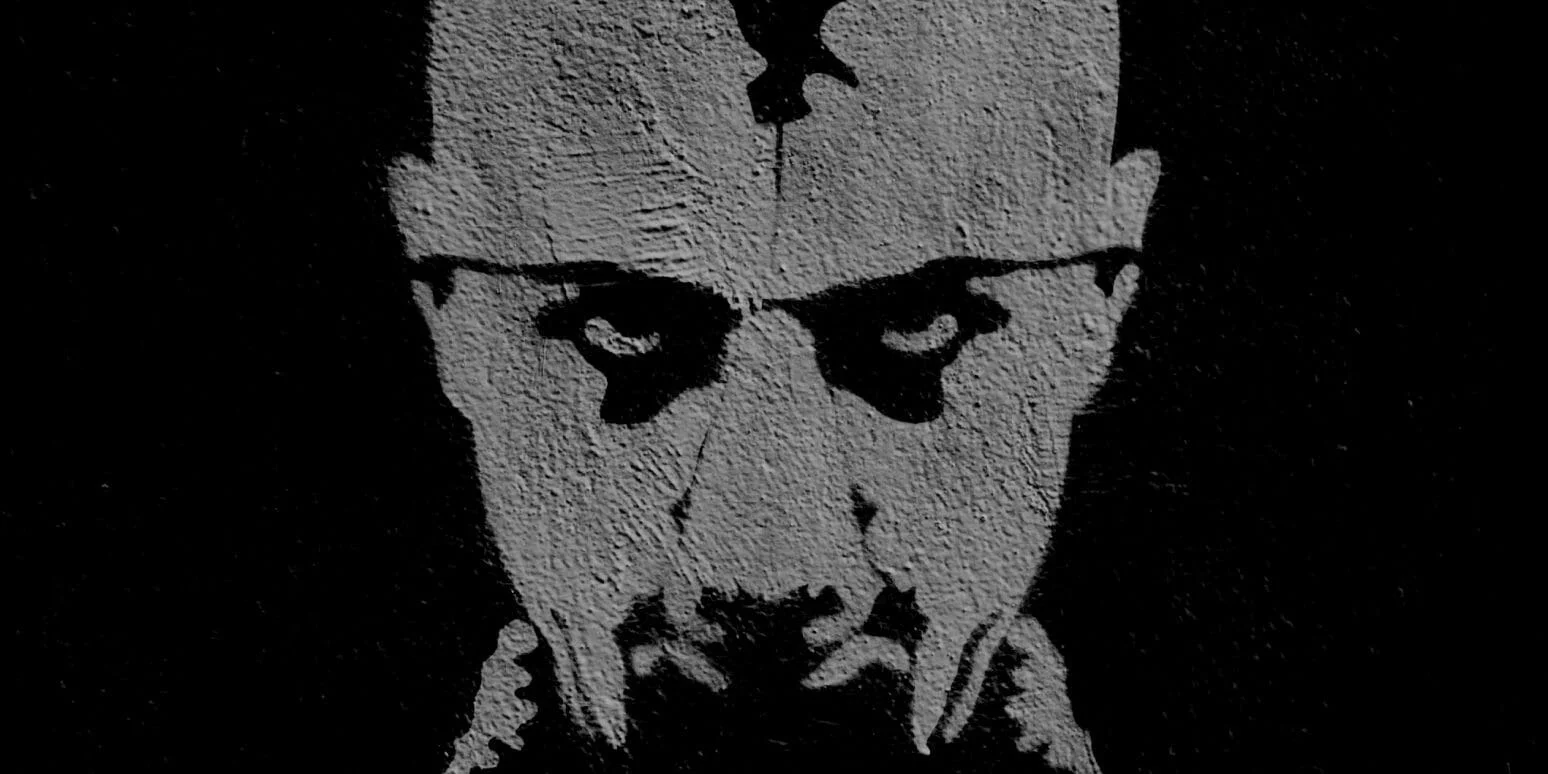

Taxi Driver is a perfect cinematic storm. It stands as one of the best-known exponents of the New Hollywood movement. It grasps 1970s America’s disillusionment with institutions after the Vietnam War and the Watergate Scandal. And it revives existentialism in cinema – the quote “Hell is other people” from Jean-Paul Sartre‘s play No Exit fits the movie better than any tagline. The legacy of this depiction of the darkest side of the psyche (of a male-man) extends far beyond movie theaters, but such an impact on the collective imaginary has also raised issues yet to be resolved.

Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), a young Vietnam War veteran, gets a job as a night-time taxi driver in New York City to try and fill his insomniac, empty life. At odds with the decadent metropolis outside his cab and apart from the passengers inside it, Travis will see his occupation only worsen his misanthropy and loneliness. And upon meeting Betsy (Cybill Sheperd), a political campaigner he can’t charm, and Iris (Jodie Foster), a child prostitute he can’t save, his ever-more shattered sanity will drive him closer to violence.

Search for a method

Taxi Driver confirmed the reputation of three then-emerging names in American cinema: Martin Scorsese, Robert De Niro, and Paul Schrader. Their breakthrough was possible because Taxi Driver was perfectly in line with the New Hollywood era, in terms of Method acting, homaging to Classic Cinema, and abiding by auteur theory.

De Niro spent time with actual veterans to prepare for his PTSD-centered performance. Bernard Hermann – the customary composer for Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock – took care of the jazzy soundtrack, essential for the noir feel of the movie. And when it came to creative freedom and personality, the movie was on par with European Modern Cinema standards.

Given the psychological subject matter, Scorsese embraced his expressionist conviction that the movie-viewing experience is akin to an altered state of consciousness, and shaped the mise-en-scène accordingly. And to make a virtue of the low budget, he achieved this vision with a French New Wave spin. That is, he filmed on location and broke some of Hollywood’s most established filmmaking rules in order to immerse the viewer in the protagonist’s world and deteriorating mental state.

And while Schrader certainly looked at American classics – especially John Ford‘s The Searchers (1956) – in his depiction of a self-proclaimed “God’s Lonely Man” he was deeply influenced by Robert Bresson‘s Diary of a Country Priest (1951) and Pickpocket (1959); as well as the works of existentialist authors of the likes of Fyodor Dostoevsky, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Albert Camus, and Sartre.

Above all though, Schrader drew inspiration from his own darkest nights of depression and isolation in New York City. Such involvement on behalf of a screenwriter was unprecedented for a Hollywood movie. But it earned the movie the Palme d’Or at the 29th Cannes Film Festival. And then, a place in thehistory of worldwide cinema.

Notes from underground

Many critics wrote about how Travis Bickle embodies metropolitan loneliness. However, the struggle of Travis is, at its core, not social but existential. On pain of self-loathing, he is on a hunt for purpose, meaning to a fundamentally meaningless life, identity. The naming of the movie after his alienating profession stands almost as a mockery of his condition.

Unlike other existential antiheroes though, other “underground-men”, Travis does not seem to reach a deep understanding of his struggle. The fact that he rarely mentions the trauma of the Vietnam War in his journaling voice-overs subtly proves this. Thus, he does not sink into analysis paralysis. Rather, he projects his frustration onto the city’s underworld in the form of misanthropy (and discrimination).

The ensuing violence is not the mere “psychic discharge” (as critic Pauline Kael calls it) of a man lacking introspection. It is a performance. The act by which a war-less warrior can signal to himself and the outside world his newfound fight, his glorious cause to kill and die for, his value. Rather than loneliness, Travis Bickle embodies, in part, what Umberto Eco defined as “Eternal Fascism”.

In the movie’s most famous scene, the protagonist faces an imaginary opponent while looking at himself in the mirror. The macho quote “You talkin’ to me?” is what has stuck in the collective memory. The underlying (self-)hate is what needs to be remembered.

Journey to the End of the Night

I don’t want to be a product of my environment. I want my environment to be a product of me.

The opening line from The Departed (2006), directed by Martin Scorsese.

Halfway through the movie, Scorsese makes a chilling cameo appearance as a deranged individual who has Travis take him to the place of his wife’s lover, a black man, and then listen to his plan of killing them both in the act. His weapon: a .44 Magnum; the same one employed by Clint Eastwood in Don Siegel‘s Dirty Harry (1971), the controversial box-office hit that spawned the trend of the vigilante thriller. When Taxi Driver came out, the hint that the media had played a role in the passenger’s envisioning of the crime was quite clear.

The scene, in a sense, encapsulates both the movie’s context of origin and its subsequent problematic allure. It was the shooting of a presidential candidate that inspired Taxi Driver. And the movie went on to inspire another shooting.

In 1981, one John Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate then-U.S. President Ronald Reagan. His aim was to impress Jodie Foster, with whom he was obsessed because of her performance as Iris. Hinckley’s attorney would then play the movie in court to plead for his client’s insanity and win the case. Hardly ever the link between violence and cinema has been so tight (the recent enamourment of the incel subculture with Todd Philips‘ Joker, which was heavily influenced by Taxi Driver and produced by Scorsese himself, also comes to mind).

While Taxi Driver does not actively glamourize violence, gender, and racial oppression, the question remains as to whether the authors let themselves get somewhat charmed by their protagonist’s violent catharsis; and whether they wish the viewer to do likewise. Schrader claims that he saw the project as a form of self-therapy. Scorsese that he wanted it to act as an exorcism for his and the viewer’s most unconfessable feelings. The movie’s ending that whether the darkest night of the taxi driver’s psyche will ever see an end is still open to debate.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic