Sapiens | An unconventional history of mankind

Author

Year

Format

First published in 2011, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind is the third publication of Israeli scholar and historian Yuval Noah Harari, and the one that brought him into the limelight. Similarly to Jared Diamond‘s Guns, Germs and Steel (1997), his aim was ambitious: depicting, in little more than 450 pages and with an all-encompassing approach, 70,000 years of evolution of humankind on Planet Earth. History, anthropology and philosophy interweave in a non-fiction book that the former US President Barack Obama recommended reading, along with Colson Whitehead‘s The Underground Railroad.

In just a decade, the book has to date sold over 13 million copies globally, translated into 65 different languages. Following its success, Harari further explored Sapiens‘ theoretical framework in two later works: Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (2016) and 21 Lessons for the 21st Century (2018). In the meantime, he has become one of the most highly-acclaimed thinkers in the world, although not one immune to criticism.

Bringing order to human history

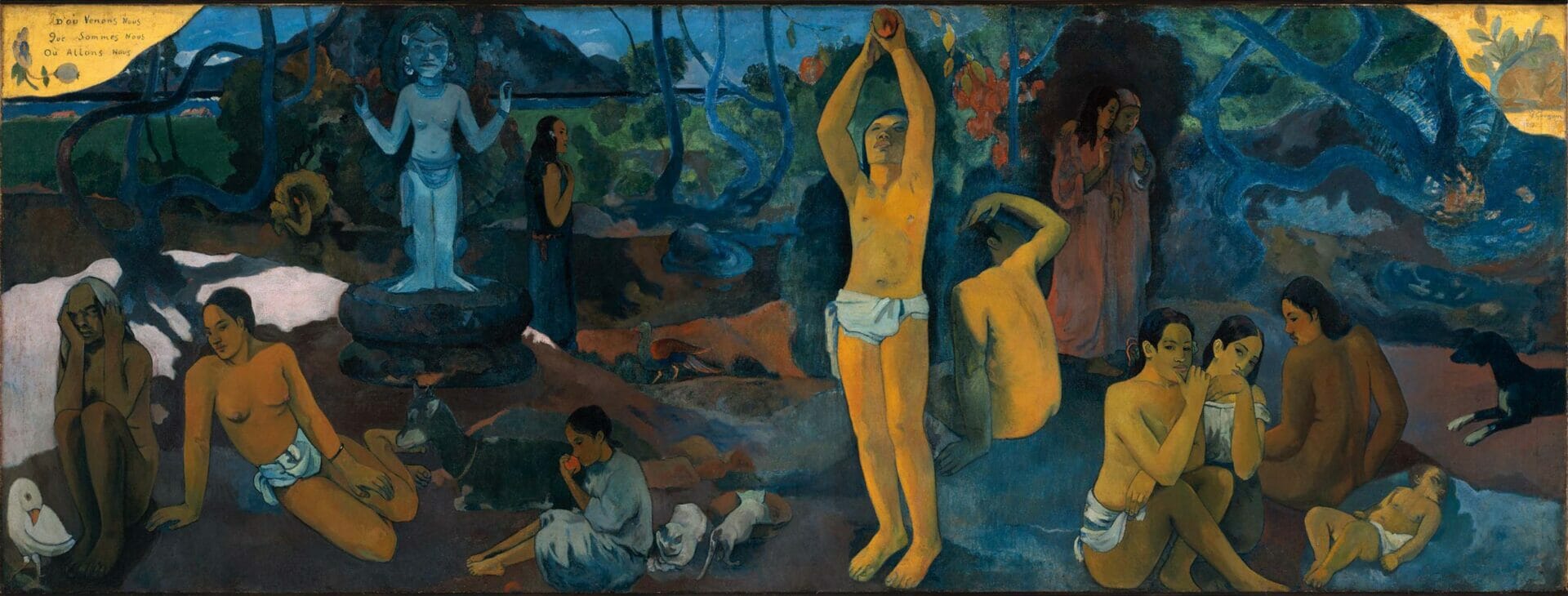

Humankind’s experience on Earth began 130,000 years ago when Homo Sapiens first appeared. The developmental proceedings from then to now is normally studied as an ordered succession of events. Instead, Harari has attempted to reorganise these events from a broader perspective, identifying crucial junctures in human evolution.

Every section making up Sapiens thus highlights a revolution, a turning point for the course of history. Starting from the Cognitive Revolution, which provided humankind with language and social patterns, to the Agricultural Revolution, which led to the first permanent settlements, the book concludes with the Industrial Revolution that sparked off just 500 years ago and projected humanity into the fast-paced economic, scientific and technological cycle of progress in which they are still immersed, guided by an insatiable attraction for the unknown.

How humankind changed Planet Heath – and vice versa

As argued by Ian Parker in The New Yorker, Sapiens is “a history of everyone, ever”. Not only because it concerns the whole of mankind’s experience, but also and especially due to its ability to raise awareness and self-consciousness in readers as human beings. Harari sheds light on the impact that humans had – and still have- on the planet since their arrival. An incisive, absorbing narrative of facts and theories entices the reader and confronts them with often hushed and uncomfortable realities.

Long before the Industrial Revolution, Homo sapiens held the record among all organisms for driving the most plant and animal species to their extinctions. We have the dubious distinction of being the deadliest species in the annals of life.

With the same disruptive sharpness, Harari highlights other side effects of capitalism and progress, from the climate crisis to the dire fate of farm animals due to mass production logic.

On the other hand, the book exposes how humanity has adapted to the environment in which it evolved. For instance, how forager ancestors were forced to turn into settled farmers by the tempting convenience and benefits of wheat cultivation, exchanging their previous lifestyle for the advancement of the species. Not a led revolution, but rather an undergone one.

This is the essence of the Agricultural Revolution: the ability to keep more people alive under worse conditions.

Real worlds and imaginary worlds: the peculiarity of Homo Sapiens

A central question throughout the book is how Homo Sapiens went from being “an animal of no significance” to having the fate of the Earth in its own hands. To say it with a film reference, what led the hominins in the incipit of Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey to the space exploration shown in the later sequences.

The key to this evolution, Harari argues, lies in the exclusive human ability to create and develop imaginary orders. Such fictitious worlds are intersubjective, as they exist “within the communication network linking the subjective consciousness of many individuals.” This peculiar category includes money, religions and nations, as well as concepts such as time, history and the future. Thanks to intersubjective orders, humankind managed to establish trust and collaboration among thousands, then millions of different individuals. This is something unique in the animal kingdom, also in its negative implications, from wars to discrimination.

The story in which you believe shapes the society that you create.

Yuval Noah Harari interviewed by David Marchese for The New York Times

In the last pages, Harari draws a provocative outline of the years to come, asserting that mankind’s ultimate goal will be to defy death. Paralleling fictional works such as Ghost in the Shell and Hiromu Arakawa‘s Fullmetal Alchemist, the author hypothesises a future populated by cyborgs and inorganic beings, living in an amortal condition and akin to gods. And yet in a perpetual search for happiness, satisfaction and meaning to their existence.

Looking for answers and asking questions

Despite its resounding public success, various criticisms have been levelled at Sapiens. In Current Affairs, the neuroscientist Darshana Narayanan claimed that the Israeli author entrusts his arguments to generic sensationalism rather than to real scientific demonstration, using persuasive and direct storytelling. Following the philosopher Galen Strawson, she also highlighted the reductionist approach of the book, determined by an oversimplification of still debated assumptions and theories. Furthermore, the author and philosopher Riccardo Dal Ferro stressed the speculative nature and the prophetic pretence of Harari’s reflections about the future.

These observations seem to be a call not to quit critical thinking and everyone’s personal pursuit of answers. Delegating such crucial practices to the seemingly simple solutions proposed by self-appointed gurus is, indeed, a frequent temptation in times as complex as the present ones.

Still, a net of simplifications and generalizations, Sapiens made a wide variety of advanced theories accessible and enticing to a large audience. Harari’s book can be approached as one of the possible interpretations of human history, a provocation and a nudge to raise questions and practice self-criticism. Not a convenient, universal and end-all answer; rather, a stimulus to create new discussions on what it means to be part of humankind.

Tag